Source: Orthodox Christian Network

By Fr. Iakovos the Athonite

Once, when I was talking to an Elder who’d been on the Holy Mountain for many years (more than twice the number I had), he mentioned the following in the course of conversation: ‘the late Father E… would always sing this doxastiko [a special hymn, sung between ‘Glory…’ and ‘Now and forever’] in the way Iakovos set it’. Since anybody who’s interested in Byzantine music knows how difficult it is to execute the settings of Iakovos the Protopsaltis (fl. ca. 1760-†1800), I was astonished and asked if Father E… knew music. The Elder seemed a little embarrassed, as if he hadn’t expected the question. He was quiet for a second or two, then said, ‘The Athonite kind’.

What he meant was that he knew more or less the settings that were normally sung on the Holy Mountain. And, he continued, in an effort to explain more clearly what he’d said and also to provide an answer to my question (where the Father had learned and knew how to sing the Iakovos setting): ‘That’s how they learned. Each one with the others’.

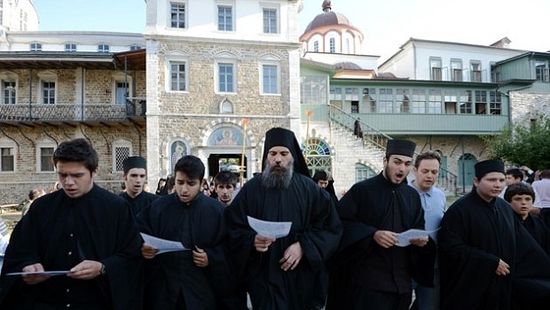

This little exchange encapsulates the way Byzantine music was learned and cultivated on the Holy Mountain fifty years ago and earlier. This was a time when contact with the external world was very limited and, for some monks, virtually non-existent. Most monks then came to the Holy Mountain at a very early age, and therefore hadn’t been able to study music and hardly had much knowledge beyond Elementary School, far less Secondary. The number of pilgrims who came was much fewer, and contact with singers and music teachers outside Athos would have been quite infrequent. In any case, the difficulties involved in getting to Athos didn’t allow for any consorting or interaction between the two musical worlds.

I came to Athos in 1993 to live as a monk, without any particular experiences from earlier pilgrimages. I was fortunate to meet the last elderly monks in the area around my monastery, and they had the characteristics I’ve just described. They had full, rich voices, thunderous, but very sweet at the same time. Their musical knowledge was absolutely specific. What they knew, and what they were used to, they sang probably better than anyone. If they saw something for the first time, they couldn’t even make a start. The chances of correcting them in what they were singing were nil.

The way they’d heard it was the way they sang it, to the end of their lives. But this was the beauty of the katholiko [the main church of the monastery]. Everybody expected to sing some musical piece with the particular timbre of their voice, and this lent a different atmosphere to the katholiko. No sooner had they started than the younger singers would look at each other and smile.

I don’t know that there was any systematic teaching. There may have been some preliminary lessons, and then the music school would have been the singing itself. Continuous singing of the repertoire would have helped the newer monks to learn, like apprentices under instruction. They didn’t much look at music in books; they’d committed some parts to memory and if, occasionally, they lost their way in the setting, they’d supply it from the closest one they remembered. Everyone had a right to take part, even those who didn’t have much of a voice or had learned from practice. You see, the services are so long and so frequent that the good singers can’t sing all the time, because they’d soon exhaust themselves.

So, in this way, quite a large part of the burden on the Holy Mountain is borne by singers who take the ‘supporting roles’. Of course, a large part is also undertaken by the abbots, and the elders, who sing the ‘pieces of the elders’. So we see that large parts of the services, particularly those that are the same, are sung by people who aren’t musicians and who, without realizing it, also contribute in their own way to the musical expression of the Holy Mountain.

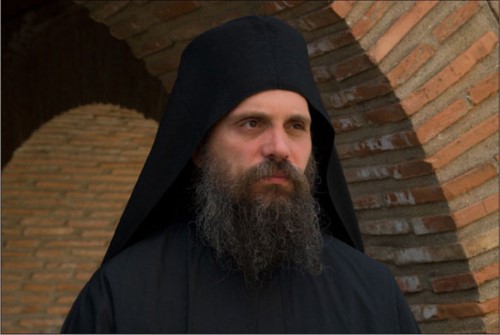

Father Iakovos, Protopsaltis of Protaton Church in Karyes, Holy Mountain

Father Iakovos, Protopsaltis of Protaton Church in Karyes, Holy Mountain

Being still new to the monastery, I talked to one of the older brothers who told me what happened in a hospital to one of the most elderly monks, who was of an exceptionally simple nature. During the course of his treatment, a whole host of people made their way to the hospital to see him and ask for his blessing, and he, for his part, would tell them something for their spiritual benefit. I reacted sharply to this. I knew that this particular father was, of course, very good and pure, but he was also very simple. What could he have to say? The other monk answered that any monk who’d spent long years on Athos, however simple he may be by nature, whatever education he’d had, would certainly have something to say.

Everyday life in a monastery is a continuous spiritual education and it’s impossible to live in one without picking up some basic things to pass on to other people. It’s my impression that something similar is also true of music.

The overwhelming majority of monks who come to the Holy Mountain, even if they aren’t given any musical training in the monastery, will certainly learn something, either from listening or of necessity. Most of them, at some stage will be able to lead the choir on the left or the right at a daily service and often will be able to sing pieces they’ve learned by ear. The time covered by these practical singers at services is very considerable, especially at the daily office. I’d go so far as to say that the we should all take into consideration the fact that the Athonite style in the faster, shorter pieces has, to a large extent, been shaped by such monks.

But it would be wrong not to mention how the spiritual life has also had an effect on worship. Many psaltists outside Athos would also say this, but on the Holy Mountain they don’t just say it; they also apply it. An Athonite psaltist never knows when he’ll sing, or even if he’ll sing. He waits to be told by the typikaris (the monk in charge of services) before coming up to his place at the music-stand in the choir. If there’s a guest psaltist, he is given pride of place over the monastery’s own.

Most often, the opportunities for choosing settings that will be musically instructive are limited, either because the abbot won’t allow it, or because not all the monks would be able to sing the chosen setting, which would result in a hiatus that the abbot would punish with a commensurate canon (often extra prayers and prostrations). Nobody occupies the first place in the right-hand choir on a permanent basis. All the Athonite monastery rules envisage an exchange of choirs (from left to right and vice versa) through the course of the year. Even the first psaltist is often forced to bear with musically weaker monks, who, perhaps, aren’t of much help to him, but also have the right to play their part.

Naturally, there are also the vigilant eyes of the elders, who will clip the wings of anybody who’s getting above himself. They’ll bring him to his senses with an appropriate canon (in this case, absence from the choir). From all this we can see that, apart from his musical efforts, an Athonite psaltist also has to engage in a spiritual struggle if he’s going to overcome all the above obstructions in order to use his music for the glory of God rather than to puff himself up. I don’t believe there’s a single Athonite psaltist who hasn’t said, at some time in his life, especially when he was just starting out, ‘I wish I’d never even learned music’.

Of course, as the elders say, these are just growing pains and happen to everyone. I confess that I had great difficulties in the early years, but my Elder encouraged me by telling me that he’d observed that monks who sang had greater grace.

And so, as the years go by, we all recognize our true position in the Church and overcome all those impediments, although they’re of great benefit to us in our spiritual life, particularly as regards the acquisition of greater humility. All of this, however, also has an effect on the musical execution of the settings. This is why I said above that the spiritual conditions have contributed to the shaping of the Athonite style of singing.

Many generations grew up in such conditions, and, of course, throughout the whole of Athos there are still elderly monks like this. Even the most prominent Athonite psaltists were nurtured by the same method. By their continuous presence at Church services and with their heightened musical awareness (it’s true that the zeal of psaltists in the pursuit of their art is extreme) and under the particular conditions of location, time and, in my opinion, spirituality, they created the much acclaimed and well-known Athonite musical style.

But we ought really to make mention of today. The Athonite style that people love is the one that was created in the manner I described above. I confess it’s not so long since I came to the Holy Mountain and, unfortunately, I didn’t manage to meet all the great psaltists of recent decades. But, by coming from the outside world with quite a good musical training, I was able to grasp, relatively quickly, how musical matters worked here

The truth is that what I see today is actually somewhat different from what I described above. Conditions are different, so it’s only to be expected that we would have a musical outcome different from the familiar Athonite style that we’ve known for so many years. This is natural, because conditions have changed. But this is not the time or place for such an analysis. For the moment let’s cling to the spiritual emotion we derive from the music of the Holy Mountain, which we know and which is loved by everyone.

Doxastikon of Saint Nicholas (Fathers of the Kelli of Danielaioi, Holy Mountain, singing):