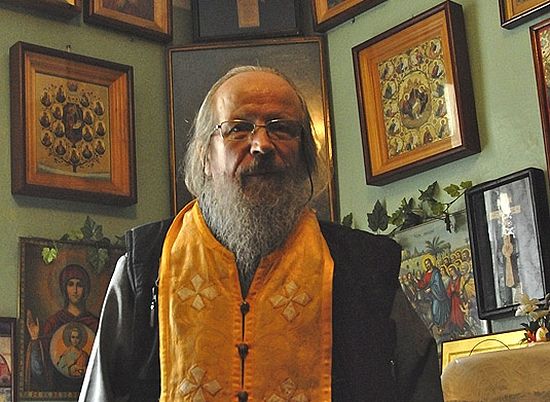

Hieromonk Nilus (before monasticism, Viktor Evgenievich Grigoriev) is one of the longest serving clergymen in Pskov diocese—he has been a pastor for over thirty years. Before that, he spent many years in the camps for political prisoners. Having received the monastic tonsure in Sretensky Monastery, he is immortalized as one of the heroes of Archimandrite Tikhon’s popular book, Everyday Saints. During one of his visits to Moscow Fr. Nilus agreed to tell us a little about his life and service as a priest.

|

| Hieromonk Nilus (Grigoriev). |

—Fr. Nilus, tell us about your life before monasticism.

—I was born in 1948 on the feast of the Nativity of the Mother of God, September 21. Only a year later was my grandmother able to have me baptized in the town of Staraya Russa, because I was a sickly infant.

My grandmother, whose name was Barbara, was a deeply religious woman. When my brother and I were little and would be falling asleep, she would kneel and pray before the icons. When we would wake up, grandma would still be on her knees. We would often ask, “grandma, did you go to sleep?” and she would reply that she had slept and was just getting up. Grandma had a very beautiful prayer corner, and she always burned three votive lamps before it in the name of the Holy Trinity.

Well, this light from the votive lamps illuminated my whole life. I especially fondly remember a little icon-statue of St. Nilus of Stolbensk—it was wooden and very old, so “handled” that the paint had worn away and the wood was completely exposed. Nevertheless, this little statue was remarkably beautiful in the light of the lamps.

Grandma often read the famous “Trinity pages” to me,[1] and I saved those pages for many years, some of which were published by the holy hierarch St. Hilarion (Troitsky)—about St. Sergius of Radonezh, St. Seraphim of Sarov, and St. Nilus of Stolbensk.

At age eighteen I began to think about the priesthood, but life was very different then, and so I first became a sailor in Cherson. I sailed the sea on yachts such as the famous “Comrade” as a bosun, after finishing nautical school.

The sea is always living and inimitable, just like the spiritual life—always living. It is not in vain that human life is often called “the sea of life”. My faith became stronger at sea.

I lived in the town of Parfino, eighteen kilometers from Starary Russa, until I was sixteen. There was a strong dissident faction there, and we grew up in that milieu; this was the 101st kilometer from the larger city.[2]

In the 1950s there lived in Staraya Russa a priest, Fr. Vasily, who served in the Church of St. George. He was about ninety years old, and all the older people would come to him for confession. There was also Archimandrite Isidore, the future Metropolitan of Kuban and Krasnodar.

Out of all those who were imprisoned in those days, I especially recall my uncle Leonid Mosin, who was taken captive by the Germans and then to the army of General Vlasov, from which he made three attempts to escape but succeeded only on the third try. He then served in the punitive battalion and helped free Berlin. At the end of the war, despite his military valor, he was imprisoned once again for ten years for having been taken captive. Grandma Parasceva, who witnessed the hanging of her husband and son by Germans, was a partisan. She was taken captive to the Treblinka concentration camp, then to Buchenwald, and was finally freed by our forces in Auschwitz. At the end of the war she was sent to the Soviet filtration camps and returned home by a miracle. Old Bolsheviks who suffered under the Soviet regime as well as Vlasov army officers who had been prisoners of war also lived in Staraya Russa.

When I served in the army in Valdai, a nationalistic fight arose among the Ukrainians. I well knew about the nationalist movement in the Ukraine and so I began to talk with them and explain things. As a result their enmity ceased and they became close friends, but the military police turned me in for political activity that was not regulated by the komsomol bylaws. I was arrested in just a few days. This was in April of 1968. At the end of April I escaped with the intention of going west to Paris and there entering the theological institute. I was arrested again during my attempt to cross the border on May 8. I was in Moscow’s Lefortovo prison for a year, almost all of it in solitary confinement. I was twenty at the time. At the conclusion of one of my interrogations, two officers said to each other, “If we had not already lived so many years we would have followed in his footsteps. That kid is winning us over; it’s dangerous to interrogate him.” They gave me seven years of prison as a political prisoner.

—What were the subjects of the interrogations?

—The subjects were: faith, the state of the regime, revolution, the murder of the royal family, and other things. I was given the option of denying my convictions, but I categorically refused.

We had political prison camps then, and I was sent to Yavas in Mordovia. There were a thousand of us in the eleventh zone. By winter the eleventh zone had been restructured, with people sent here and there to other zones. In Yavas, where we were taken first, there was still a trench dug out by a bulldozer, and next to it stood a so-called “untouchable” bulldozer which was supposed to bury the prisoners who would be shot under Khrushchev’s secret orders when the time came.

In the village of Barashevo which surrounded the third zone there was a half “t” shaped trench where the children of the “enemies of the people” were executed—there were 25 thousand people buried in it—and in another trench parallel to the first were buried 20 thousand clergy and ecclesiastical workers. The elderly commissar of the Dubrav camp told us about this. Young pine trees grew on these mass graves.

—Did you ever meet with any religious believers in those places?

—In the village of Barashevo (this was from 1970–72) an Orthodox community arose around us. We would continually gather and pray. There was a bath house built there in the shape of a half “t” by German prisoners of war, and we would meet for prayer in the inner corner. Sometimes five or six people would come, up to fifteen on feast days. I remember Valery Zaitsev, a former sea diver; Victor Chesnokov, a Kuban Cossack; Sasha Udodov, a military historian who studied military arts of Russia from ancient times to the present. After his release he left for Norway; Evgeny Vagin, who died in Italy two years ago, and who had been part of a group of Leningrad Christian Democrats led by Igor Ogurtsov; Michael Yukhanovich Sado, from the same group—an exceedingly noble Assyrian who later taught ancient Hebrew and church architecture in the St. Petersburg Theological Academy. At his recommendation, I audited lectures at the academy, including those of the current Patriarch Kirill who was dean of the academy at the time. I remember also Viacheslav Platonov, an oriental studies scholar. Peter Savvich was an active participant of our community. At age fifteen he was taken out of the country to Berlin, from Suma province to Dresden, where he helped put out the fires after the American firebomb attack, and was subsequently arrested for this in 1945 by the NKVD. Andrei Donatovich Sinyavsky was also imprisoned with us. He was a literary scholar, and in 1972 he was sent to Paris without having been given an opportunity to change his prison clothes. His wife, Maria Rosanova, the daughter of the famous philosopher, gave him civilian clothes in Paris.

There were also old priests there: Hieromonk George from the catacomb Karlovac Church. He was one of the young priests of his time who served in Chita and refused to cooperate with the communist organs. How did we serve? Nothing was allowed—no Bibles, or anything. There was a deacon there who knew the order of services by heart and we took them down from him, but because he was afraid to go to the services, Father Boris delegated the reading of them to us. I would also read part of the litanies. “Father, after all, the rules do not allow it!” “No, no,” he would answer, “You are going to be a priest, so say them without fear.” In such extreme situations a person shows his true colors and therefore batiushka saw clearly and spoke plainly. Father George, who had spent thirty years in prison, also treated me as he would a priest. There was also blessed Emilyanushka, and Father Boris Zalivako.

—They say that those who lived through the terrible Solovki concentration camps and other prison camps felt special help from God. Have you had any personal experience of an awareness of the Lord’s nearness?

—One feels the presence of God and His grace-filled help continually. Once I was shut up in punitive isolation for fifteen days. The walls were coated with ice. When they took me there I was wearing old fake leather slippers without socks, cotton pants, and a jacket. They shove you into this freezer about 2.5 x 1.2 meters in size. Inside is a concrete and metal little stump that you can sit on for a short time. There were bunks in the isolation chamber that were made of oak, but it was impossible to sleep on them; if they had been made of aspen you could have laid down on them but oak does not get warm. We had to sleep standing up or sitting. We were fed every other day. For lunch we were given a mug of hot water and watery gruel, for dinner—nothing, for breakfast a mug of water and 250 grams of bread. Of course we would walk around just to warm ourselves a little, and pray. The guards would take a look at us every now and then to see if we were still alive. I began to feel sorry for my overseers, and said to one of them, “Why did they put you here, Andriusha? As for me, I know why I am here—I am guilty before the state. But what did you do? You are imprisoned just like me; the only difference is that you are you have a coat, your clothes and shoes are warmer, you eat better, but that is the only difference. Your soul is just as shackled.”

That lad was of Cossack stock. On the last day he opened the door, took out some food—he had brought me some fresh herring and some tea. “Only eat it in front of me,” he said. But I knew better than to torment myself with herring, because salted fish in a jail cell means excruciating thirst. But he said, “I am on duty today and I will provide you with tea. It is just that I don’t have anything else or I would give it to you.” We sat there and talked all night. He said, “This is my last night—I leave tomorrow. I have no more strength to stay. I thought and thought about it. I can see why you are here, but why should I be here with you?”

The second time they gave me forty-five days. They didn’t have the right to give it to me all at once—only fifteen were allowed. So here is what they did—they took me out for a half an hour, and then gave me another fifteen day sentence, and that is how they got forty-five. True, the first time I came out I was holding on to the walls but I was on my own two feet. But the second time they took me out on a stretcher, to the morgue. My body couldn’t handle it. I saw from the other world how they picked me up, shook me, and then carried me away. The head of the sanitation department was a Jewish woman, a major. She saw me and asked, “Who are you carrying?” “Just a goner from the cooler, he’s kicked the bucket.” “Wait just a minute,” she said.

This was my second experience of death, in which I heard the voice of God. “Send him back, he has to serve a while more,” and then I came to. I looked and saw the Mother of God leaning over me, and then the head of the sanitation department ordered, “Take him back to the hospital, to my wing.” She worked in the surgical wing. She kept me for three weeks in the camp hospital. Before I was released she spoke with the chief administrator. “I won’t let you kill this boy,” she declared.

I worked in that camp for two years—I chopped wood. The convoys would bring the logs and we would saw them with a circular saw. The plan was five cubic meters per day. Later I took a fancy to the welding machines in the mechanics shop and asked to be transferred there, and so I was. After working in that shop I began to study machinery and kinetics. This was easy for me because I always loved reading books, even since childhood. Bookstores are still my favorite places. Our school library was a good one, and I had read everything in it by seventh grade. There wasn’t a single book there that I had not read.

That is why it was so easy for me, and I soon picked it up and passed an examination with the chief engineer, who immediately assigned me to the third level. Later I maintained six-spindled German machines—there was an automated assembly line—and then I had to set up a rolling mill. That is how I gradually got used to camp machinery.

After I was released I worked as a mechanical technician at a factory, and then entered the technical institute. But I wasn’t able to continue my studies there because I had to eat, and my stipend was too small. I started working during the day and studying in the evening.

On Saturdays and Sundays a journalism docent from Leningrad University would come and teach us photojournalism. We did photo reportage for literary texts. It was all very interesting to me, and so I began to get into cinematography and photography, studying these subjects as an extern.

—In what year were you ordained?

|

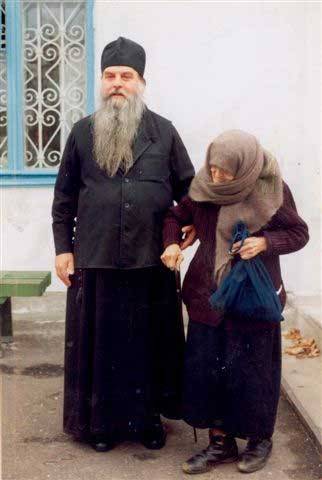

| Archimandrite Agathangel (Dogadin) |

Archimandrite Agathangel (Dogadin) from the church of St. Phillip in Novgorod, my father confessor, said, “Stop your worldly affairs and go to a monastery.” That year, my grandmother Barbara died. Fr. Agathangel sent me to Zhirovetzy Monastery.[3] Thus I left everything—the institute and a new, comfortable apartment, and went to Zhirovetzy.

At that time in Zhirovetzy the abbot was Archimandrite Constantine (Khomich), and the dean was Archimandrite Athanasius (Kudiuk). But the Cheka did not allow them to accept me. Archimandrite Athanasius was friends with Archimandrite Leonid, the abbot of the Holy Spirit Monastery in Vilnius; that is how I ended up in Vilnius. There Fr. Leonid came to me on the second day and said, “They (the KGB) want nothing to do with you.”

After that I headed for Pechory, to Fr. Gabriel [Archimandrite Gabriel (Stebliuchenko)—the abbot of the Pskov-Caves Monastery from 1975 to 1988.—Ed.], but they would not let me stay there either. The abbot gave me back my identification documents, some money for the road, and told me to go to the bishop. I went to Fr. John (Krestiankin) and he said to me, “Go to Vladyka [the bishop]. I went to Bishop John [(Razumov) (1898–1990), Metropolitan of Pskov and Porkhov.—Ed.] and he said to me, “Son, go again to Fr. Agathangel since you consider him your spiritual director. We have a priest here named Fr. Panteleimon, in Melnitsy, and if your spiritual director so blesses you, then go to help Fr. Panteleimon.” I went to Fr. Agathangel and explained the situation to him. This was in 1980, the year Moscow hosted the Olympics. Fr. Agathangel sent me to Melnitsy to help Fr. Panteleimon.

I ended up in the village of Melnitsy, to serve the church of the Archangel Michael, where Igumen Panteleimon received me in the capacity of guard and psalm reader. Fr. Panteleimon was an energetic man; he remodeled the church in Borisov which was falling into ruins, and then began serving in Melnitsy. I stayed with him there for a year. Just the same, I did not see any point in staying with Fr. Panteleimon. I went back to Fr. John and said, “Father, you yourself know that he is illiterate—he makes mistakes when he reads the Gospels. When I try to explain something to him he says, ‘You want to teach me?’” I asked Fr. John if I could go to Fr. Boris in Tolbitsy. “Alright,” he said, “I will talk with the bishop,” said Fr. John. The bishop listened and said, “In fact you are needed in Tolbitsy.” Fr. Boris had also been in prison for six years—he was sentenced before the war (1937–43). In 1937, when the authorities arrested everyone in the parish in the town of Ostrov in Pskov province, where he served as a deacon, he was the only one who was saved—his wife saved him.

Fr. Boris was an invalid and so he was sent to the invalid zone in Vladimir province—he was half blind. When he was just a child he led a blind priest from the military administration to the church of the Holy Myrrh-Bearers in Pskov. His mother was a famous “esser”,[4] and she did not want him to be helping any priests. She called him a “popovskoe otrodie” or “priest’s spawn” and hit him so hard on the back of the head that he lost his sight, remaining 50% blind.

After Fr. Boris’s arrest, his wife Maria sold their house in the town of Ostrov and used the money to go to the village where Fr. Boris was imprisoned. She bought a log bathhouse and turned it into a residence, obtained two goats, and revived Fr. Boris with their milk. Thank to this he survived.

After Fr. John’s intercession, the bishop sent me to Fr. Boris. On the feast of the Three Holy Hierarchs I was transferred to Tolbitsy. I served with Fr. Boris for four years; Fr. Nicholas (Guryanov) served not far from there. I felt good there; it is a blessed place—whenever any problems came up I could run to Fr. Nicholas for a speedy resolution.

—What do you remember about Fr. Raphael (Ogorodnikov)?

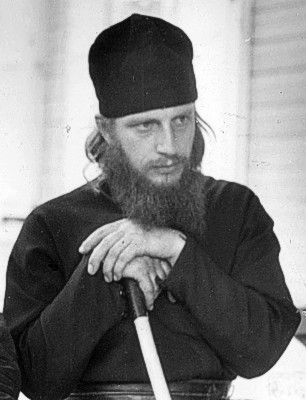

|

| Hieromonk Raphael (Ogorodnikov). |

Wisdom and humility, eagerness for obedience—these were Fr. Raphael’s qualities. Once a young boy came up to him and said, “Don’t eat any eggs today, father.” Fr. Raphael was always seeking some excuse to be obedient, and it was Tuesday, not a fast day, but he nevertheless heeded the words of this ordinary little boy. The women who worked in the kitchen later said that the eggs were spoiled that day. This constant yearning for obedience always helped Fr. Raphael through many situations in life.

—What is an elder?

—I remember a conversation I had with Fr. John (Krestiankin), who said that elders are given by God. “Eldership is a gift of God, and it is only given when there are those who will listen and obey the direction given to them through the elders. However, man is full of infirmities; for instance, he will ask for a blessing from someone, then another, a third, a fifth, a tenth, and so on… But he doesn’t fulfill any of this advice. The Lord will correct such a foolish man, because he takes too much upon himself out of his foolishness. The ancient fathers would say, if you have chosen an elder for yourself, stay with him to the end.”

One woman asked me to bless her to make prostrations and pray the Jesus prayer. Before she met me she had practiced a purely monastic prayer rule. I asked her, “Are you a nun?” She replied, “No, I am only planning to be one. Maybe Fr. Raphael will tonsure me.” That often happened in Soviet times—nuns would be tonsured in parishes. “Well, if you want to practice the Jesus prayer: say the prayer once in the morning with a prostration, once at noontime with a prostration, and once in the evening.” She said, “Are you making fun of me? What do you take me for?” “I am not taking you for anything. God bless you—if you can fulfill this obedience then come back in a month.” A month later she returned, weeping. “Please forgive me for getting angry with you. I can’t do it—whenever I only think about having to make prostrations ever fiber in me rises up against it, and I can’t.” “Well, you’ve taken the path of experience and seen that you can’t do it. What if you take monastic vows—then what will you do? Then you will have to fulfill the rule whether you want to or not,” I answered her.

—Fr. Nilus, did you know Fr. Dositheus?

—I visited him several times. I remember how Fr. John talked about Fr. Dositheus. He said that he was one of the last great pillars, who emulated the ancient holy fathers. His cell was made of logs. At times he would get sick but he would not heat the stove—he would just wrap himself in rags and lie there. After the illness had subsided he would rise and heat the stove. People would come to Fr. Dositheus but he would just continue with his life, not saying anything in particular, only going on with his work. When the time would come for prayer, he would stand by the analogion, open his prayer book, horologion, or Ochtoechos, and begin to pray. The visitors would pray with him.

I remember one Great Lent when he fell sick and the doctor pronounced a death sentence. “That’s it father—in two months order some boards and make yourself a coffin.” Fr. Dositheus closed his doors and went into reclusion, not opening up to anyone. He came out only on Pascha to the church where Fr. Nikita served, and his face was pure and white. Fr. Nikita said later, “I didn’t recognize him.” “How could that be? Didn’t he raise you, feed you?” I said to him. “He had changed so drastically, had become such a luminous man,” replied Fr. Nikita, “that I did not recognize him.” Fr. Dositheus had a favorite icon of a golden-haired angel, and he began to resemble that angel.

He lived two more years and died on Pascha, when his boat capsized. They served Fr. Dositheus’s funeral using the Paschal rite on Bright Thursday. They brought him into the monastery amidst the ringing of the Paschal bells. What an honor he was vouchsafed—to die on Pascha! He had received Holy Communion from Fr. Nikita at the Pascal services. Fr. Dositheus was a remarkable monk…

—Fr. Nilus, you have been serving for twenty years now in the most remote parish in Pskov diocese, in the village of Krasikovshchina. Tell us about your parish life, and how you built it.

—There is almost no one left the parish. The light burns in only six houses. On the New Year grandchildren come to see their grandmas and relatives, but otherwise you see people there only rarely. The squealing of children isn’t even heard in the summertime. Two or three old ladies are left. They have even closed the store; there is no grocery store, no water—only elderly people ambling around.

But when I arrived there twenty years ago there were fifty people, and they would put fifty privately owned cows to pasture each day. Then everything went to rack and ruin, the stables were closed, and now the village has no cows at all.

Very few parishioners are left. Over the last twenty years I committed the whole parish to the earth.

But when I served in the village of Tolbitsa (1981–1984), I had three cats, a dog, and six rats living in my house. When I would rise in the morning for prayer, turn the pages of my service books, animals would begin a lively conversation. I would say to them, “Silence!” They would sit in one position as if hypnotized, no one making a motion. They would sit quietly until I finished reading the Octoechos, but as soon as I would close the book they would squeal for it was time to be fed. There were about ten snakes living on my porch. I had a cat that would fly at them—I would look and the snakes would all be headless.

If you ever have to live in the desert or the forest, don’t be afraid. When we were walking in the mountains—I used to be a mountain climber—I once had to crawl along a slope, and there was a Levantine viper on the rocks with which I found myself face to face. It raised its head and looked at me. When this happens you must not make a move, not even a wink. It looked at me and lowered, but it was in a combative position. But if I had made a move it would have leapt at me then and there. I had to wait until crawled down from the rock. The main thing is not to be afraid, and then nothing will happen. It is the same with bears and wolves. But the most basic thing is that all of nature feels God; this is directly connected with God’s grace, and when a person is filled with prayer, the animals feel it.

|

—The thing is that we try to teach with words, but parishioners learn by example—they look at how you live. For instance, they bring food offerings to the services for the dead and look to see whether I take them or not. The priests in the towns would take them and so did I—on my way to Pechory I would take them to the children’s home. But what could I do with them in Krasikovshchina? It would all go bad. I told my church warden, a humble woman (we don’t even have a church council now), “Parasceva, tell the ladies to take the offerings home because I don’t need anything.” I could hear a rustling and then everything was gone. My mistake was that when they would go to services at the neighboring parish, they would say to Fr. George, “Our priest doesn’t take anything but you take it all. Are you selling our candy?” When I saw Fr. George he laughed and told me how his grandmas would criticize him. I said, “Tell them openly that you take it all to the children’s home.” After this they said to me, “Father, Fr. George told us that he takes the offerings to the children’s home. Why don’t you do that?” “I don’t have anything to take, you take it all.” “Well, you tell us not to take anything and we won’t.” I protested that I don’t have any way to take it there but they said later, “Now you have a car—take the offerings.”

So then I had to start taking all the candy from the services for the dead to the children’s home. There the little children would meet me joyfully. “Oh, father has come!” These are little tots, three or four years old, God’s angels, little wonders. In order to cultivate a Christian spirit in them I would read to them the teachings of St. Theophan the Recluse, or the letters of Fr. John Krestiankin. Sometimes I would stop and tell them something from life. Priests rarely came to them.

|

| Fr. Nilus's flock. |

After his death his wife took monastic vows in Diveyevo Convent, and later became Schemanun Maria. (She has already reposed.)

|

—I remember when I was serving in Khokhlovy Hills, Porkhov region (1985–1989). We had just finished restoring the church. It was autumn, and the regional authorities came to investigate. They walked around clattering their teeth, and then said to me, “It would have been better for you to give that money to the peace fund.” I replied, “I do give you the money for the peace fund. Enough for a bottle—have a drink and you’ll be at peace.” One said, “He’s an idiot.” But the second one said, “Maybe he’s an idiot, but look what he’s accomplished—the church is new.” Of course, the church was always tidy—the iconostasis was cleaned and gleamed with gold. During those four years we worked from sun up to sun down, sleeping two or three hours a night.

In the second church in the village of Pavakh (1990) I had to replace the roof. Metropolitan Vladimir rewarded me for that labor with a blessing to wear a scufia.

|

| Krasikovshchina. |

The rector of the church of the Nativity of Christ in Krasikovshchina, Fr. Vladimir was arrested along with his family after a denunciation by the local inhabitants in 1937. He was executed in St. Petersburg, and his family was drowned on a barge. After Fr. Vladimir’s death only one church was left open there, the church of the Nativity of Christ. The second is still in ruins.

Three years ago I served a funeral for the last old lady who signed a denunciation to the Cheka against Fr. Mikhail Elagin, who was the rector of the Church of the Nativity of Christ after the war. Thanks to this old lady that priest spent ten years in a prison camp in Vorkuta. But good for her—she repented. When she came to me during Great Lent I asked her, “Maria, where will you go with that unrepented load? You could die any day.” She broke into tears and said, “I repent, and have repented all my life. When Fr. Mikhail comes I hide, I lock myself up at home, because I am ashamed to see him.” I replied, “This time when Fr. Mikhail comes ask his forgiveness.” After Pascha, on the feast of Pentecost, when Fr. Mikhail came Maria went to him and asked his forgiveness. Fr. Mikhail could have guessed who wrote the denunciation. He truly forgave her, kissed her, and said, “Mashenka, be at peace, I have forgiven you.” Glory be to God, her soul departed clean, without that sinful burden. Fr. Mikhail also departed in tears. One day he came to me and wept. I asked him what he was weeping about. Fr. Mikhail was feeling that the time of his death was near. “Well, father, I have to depart soon.” I said, “This is ordinary business for us, father. With all the dead we have buried, what do we have to fear?” “No,” he said, “I am not afraid of death, but of sins.” “Go ahead and tell me the sins you can remember.” We confessed each other. Fr. Mikhail departed this life quietly, and peacefully. He was buried next to his wife in the graveyard at the Church of the Holy Myrrh Bearers in Pskov.

—When did you meet Fr. Tikhon [Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov), abbot of the Moscow Sretensky Monastery.]

—My meeting with the future Fr. Tikhon was interesting. Fr. Raphael, Fr. Nikita, and I were at the homestead in Logu in the museum of the writer Altaeva, which I was visiting for the first time. There we met Fr. Tikhon. He had a movie camera with him, and was filming some interesting compositions. I asked, “Who is that?” They answered that it was Georgiy Alexandrovich Shevkunov, a student from the Cinematography Institute, a spiritual son of Fr. John (Krestiankin), and Fr. Raphael’s very close assistant. We introduced ourselves. He was a sociable, open-hearted person who was in his third year of study. I also had at that time a small, eight millimeter camera. He looked at me with such surprise; he had a serious camera, and he asked me, “Father, what are you going to do with that?” “You are filming and I also like to film.” “But where will you have it developed?” “I’ll have it developed somehow.” But I didn’t develop anything. Only a few pictures of Fr. Nikita are left.

—Tell us about your monastic tonsure. Why did so many years pass before you finally made that decision?

—The Lord has led me all my life, from childhood, even infancy, to the angelic field. But apparently it pleased God to have me take that step with full responsibility, understanding, and spiritual insight into the meaning of monastic life. From the moment of my tonsure my life changed abruptly. After the bishop signed the order for my tonsure, I went to my father confessor Archimandrite Tikhon, who then performed this great Mystery. Here, in Sretensky Monastery, I was born as a monk. I am learning spiritual warfare, spiritual concentration, and how to walk in the presence of God, so that I might not forget the Lord for even a second.