Saint Ermenburgh

A stained glass of St. Ermenburgh (Domneva) of Thanet

A stained glass of St. Ermenburgh (Domneva) of Thanet According to tradition, a tragedy happened in the kingdom of Kent in about 670 (some sources give the year 669): an adviser of king Ecgbert cruelly murdered two very devout and very young brothers Ethelbert and Ethelred—the latter were sons of king Ermenred and younger brothers of Ermenburgh, therefore, cousins of Ecgbert. It is not known if the brothers were killed by order of Ecgbert himself in order to get rid of any rivals to the throne, or on his adviser’s own initiative. However that may have been, there was a serious political dispute within the royal family at that time and the innocent youths were its victims.1

Learning about the murder, the holy queen Ermenburgh demanded a wergild, that is, an atonement for her close relatives’ killing, as was the custom of that time. As she never thought of money or any riches, she asked King Ecgbert to bestow land to found a monastery in Kent. Significantly, Ermenburgh wanted to build her monastery on the Isle of Thanet in northeastern Kent, where St. Augustine with other Italian monks had arrived in 597 to convert the Angles. King Ecgbert was full of grief and repentance and gladly consented. The queen requested that the land that her tame hind was to walk around would be allotted to found a monastery. The hind walked around a vast area in Thanet and it was decided to found a nunnery there. The hind ever since became the symbol of this abbey.

The convent in honor of the Mother of God, founded by Ermenburgh, was called a minster, from the early English word, derived via Latin from the Greek word “monasterion”, which means “monastery”. So the site since then has been known as Minster-in-Thanet. After the repose of her husband in the 670s, Ermenburgh took the veil and with time became the first Abbess of Minster-in-Thanet, wisely ruling over some 70 nuns. In about 694 Ermenburgh resigned her abbacy in favor of her daughter Mildred who became the second and greatest Abbess of Minster. Ermenburgh reposed between 695 and 700 and was venerated as a saint after her death—as a holy woman and foundress of Minster. Thus, providentially, the tragedy that occurred in 670 led to good—two new saints of God appeared (Ethelbert and Ethelred) and a new monastery was founded that was destined to have a great future.

Saint Mildred

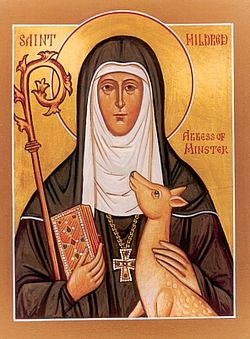

Icon of St. Mildred of Minster

Icon of St. Mildred of Minster Returning to England, Mildred stepped on the coast of Kent in the place then known as Ebbsfleet, where lay a large square rock, miraculously prepared for her beforehand, on which an imprint of her foot remained forever. Afterwards many miracles occurred from this rock—even water mixed with dust or tiny pieces of it had healing powers. Later this rock was kept in the Thanet Convent as a great relic, and with time it was placed inside a specially built chapel. St. Mildred’s rock existed for many centuries after Mildred’s life.

In England Mildred was tonsured by the saintly Archbishop Theodore of Canterbury and entered the Minster Convent on the Isle of Thanet, that had been founded by her mother Ermenburgh. No earlier than 694 Mildred became the second abbess of Thanet after her holy mother. As abbess of Thanet, Mildred gave an example of holy life, wisdom, love and kindness for her sisters and disciples. In all things she was gentle and humble, and everybody loved her very much as a caring and loving mother. Mildred already in her lifetime worked many miracles. Once a demon blew out a candle in the church while Mildred was praying there, and an angel at once drove the wretched spirit away and lit it anew. The eleventh century Life of Mildred describes her as “always merciful, always meek, and always quiet.” The holy abbess was a real protectress of the poor, the destitute, widows and orphans. She remained the heavenly patroness of them after her repose as well. Like some other female saints of the age, St. Mildred was the protectress of wild geese with which the fields of Kent abounded.

Mildred reposed early in the eighth century (according to different versions: about 700, 716, 725 or 732) after a long and painful illness. The successor of Mildred as third abbess of Thanet was St. Edburgh. Veneration for Mildred as a saintly maiden started straight after her death; with time she became known as “the wonderworker of all Kent.” Many miracles occurred near her holy relics and the saint’s biographer stated that no blind, dumb, or deaf person, nor anyone suffering from any other ailment of soul and body and came to her church, left without healing and consolation. There were cases of posthumous apparitions of Mildred. Thus, during the abbacy of St. Edburgh a bell-ringer once fell asleep, sitting in the convent chapel. The saint then appeared to him, hit him lightly on his cheek and said: “This is a chapel, not a dormitory.”

The shrine with St. Mildred’s relics was a permanent destination for pilgrimages by faithful Christians for many years, and the holy virgin-abbess for a long time was among the most venerated woman saints of England, especially in southern England. Like other English monasteries, Minster was repeatedly raided by the pagan Danes. Soon after one such pillage of Minster by the Danish invaders the relics of St. Mildred were translated to the church of St. Augustine’s Monastery in Canterbury (c. 1031)—perhaps on the orders of King Canute—where they were kept for many years, and where the saint was held in high esteem. It was also said that during the ravages of the Vikings in the same century a small portion of St. Mildred’s relics together with St. Milgyth’s relics were translated to the monastic church of St. Mary in Lyminge in Kent. In the second half of that century a portion of St. Mildred’s relics (possibly from Lyminge) was donated to St. Gregory’s hospital in Canterbury.

St. Mildred's Church in Nurstead, Kent

St. Mildred's Church in Nurstead, Kent

St. Mildred's Church in Acol, Kent

St. Mildred's Church in Acol, Kent

St. Mildred's Church in Tenterden, Kent

St. Mildred's Church in Tenterden, Kent  St. Mildred's Church in Canterbury

St. Mildred's Church in Canterbury St. Mildred was venerated outside England as well, in what are now France and the Netherlands. It is certain that a portion of her relics was kept in the city of Deventer in Holland (it was from there that her relics returned to her motherland in the twentieth century). Apart from Minster-in-Thanet and Canterbury, another place of our saint’s veneration in England was Ebbsfleet, mentioned above. One hundred years before St. Mildred, the enlightener of the English, St. Augustine, had landed on the same site. Popular veneration for Mildred there was so strong that it even overshadowed the veneration of St. Augustine, so Ebbsfleet was called by some “Mildred’s rock”. Many ancient churches were dedicated to Mildred in the south of England, and some of them still survive. There are Anglican parish churches dedicated to St. Mildred in the following places in Kent: Preston; Nurstead (dating back to 1340); Acol; Tenterden (dating back to the 12th century); and Canterbury. The latter is the oldest of the city’s twelve surviving parish churches standing within Canterbury walls, and dates back to the early eleventh century, so it is pre-Norman. There is also a Church of St. Mildred in Whippingham on the Isle of Wight, and even London has two churches in honor of St. Mildred—in Bingham Road (Croydon, Greater London) and in St Mildred’s Road (Lewisham, Greater London).

St. Mildred's Church in Whippingham, Isle of Wight

St. Mildred's Church in Whippingham, Isle of Wight

St. Mildred's Church in Bingham Road, Addiscombe, Croydon, Greater London

St. Mildred's Church in Bingham Road, Addiscombe, Croydon, Greater London

St. Mildred's Church in St Mildred's Road, Lee, Lewisham, London

St. Mildred's Church in St Mildred's Road, Lee, Lewisham, London Among notable churches which no longer exist but formerly were dedicated to St. Mildred we can mention the following: the church in Bread Street in the City of London (the medieval church was first destroyed by the fire of 1666, then it was rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren. Early in the nineteenth century the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley married his wife Mary precisely in this church. In 1941 it was sadly destroyed by German bombing); St. Mildred’s church, Poultry, in the City of London (built in the twelfth century, rebuilt by C. Wren, and demolished in 1872); the church in Ipswich, the county town of Suffolk, which stood on the site of the town hall that was built in the nineteenth century (the temple there may have been founded soon after St. Mildred’s repose!); and the medieval church in Oxford on the territory of Oxford University’s Lincoln College (it was demolished in the fifteenth century. In 2009 sculptures of the Holy Virgin and St. Mildred were installed in the niches of Lincoln College’s front tower). A number of churches dedicated to St. Mildred can be found in the French department of the Pas-de-Calais, including a chapel in the commune of Milam. She is also venerated in Utrecht and elsewhere in the Netherlands.

“Mildred” was a common baptismal name among women living in rural regions of England until the end of the nineteenth century. Some girls are given this name in England to this day. The name “Mildred” is also widespread in New England in the USA. No wonder that several Catholic churches in America bear the name of this ancient English saint. St. Mildred is usually depicted holding a church, with a hind, or with three geese (she protected the crops from these birds and they obeyed the abbess, according to her life).

Saint Edburgh

St. Edburgh of Minster in Thanet

St. Edburgh of Minster in Thanet In Minster Edburgh rebuilt the convent for her nuns and built a new abbey church dedicated to the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul (patrons of a whole host of early English churches) in which she placed the precious relics of her spiritual mother, St. Mildred. The holy maiden of Christ also secured several royal charters with privileges for her convent. Under St. Edburgh Minster may well have controlled half of Thanet. After many years of unceasing labors the holy abbess reposed in the Lord peacefully in 751. Her relics were enshrined inside the church, and very many cases of healing miracles from her shrine were reported. Later, in the eleventh century, the relics of St. Edburgh and a portion of the relics of St. Mildred were translated to the Hospital of St. Gregory in Canterbury where their veneration continued. Notably, the early English Church can boast five female saints with the name “Edburgh”. In addition to Edburgh of Minster, there were Edburgh of Bicester (mid-seventh century. Part of her shrine exists in the Church of the Archangel Michael in the village of Stanton Harcourt in Oxfordshire), Edburgh of Lyminge (a nun of the seventh century), Edburgh of Repton (during whose abbacy St. Guthlac of Crowland became a monk at her double monastery) and Edburgh of Winchester (a nun and wonderworker, granddaughter of Alfred the Great, who reposed in 960 and was venerated in Winchester in Hampshire, Westminster in London, and at Pershore in Worcestershire).

The Monastery in Minster-in-Thanet

At the time of St. Augustine and the holy abbesses of Minster, Thanet was a real island separated from the mainland (Britain) by a wide channel. Today it is part of the mainland, slightly “separated” by two branches of the River Stour. In the spiritual sense, Kent where Thanet is situated is the cradle of post-Roman Orthodoxy in England, and Thanet is its gem as Augustine stepped on the English land precisely on Thanet and prayer has continued here for more than 1300 years. Nowadays Minster-in-Thanet, formerly known as “the capital of Thanet”, is a village with a population of just over 3,000 people. It is situated west of the town of Ramsgate and to the north-east of Canterbury, the capital of English Christianity. The coastal town of Ramsgate is also known as an ecclesiastical center: the modern Roman Catholic Benedictine Monastery existed here for one and half centuries.

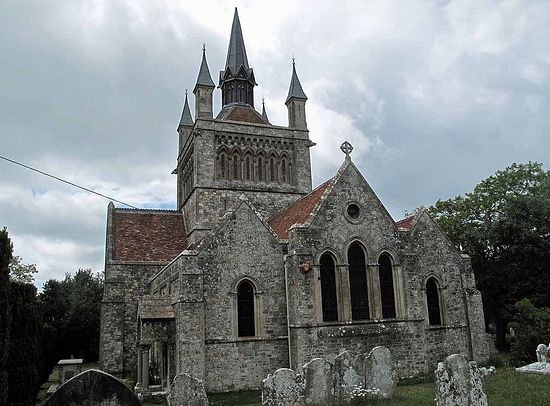

St. Mary's Norman Church in Minster-in-Thanet, Kent

St. Mary's Norman Church in Minster-in-Thanet, Kent

Roman Catholic Benedictine abbey in Minster-in-Thanet

Roman Catholic Benedictine abbey in Minster-in-Thanet Today the village Minster can boast two shrines: one of them is the Anglican Norman Church of St. Mary the Virgin with some late English elements, and the other is the Roman Catholic Benedictine Priory of nuns dedicated to St. Mildred. Both of them have close links with the original Minster Abbey. The present Anglican church was built in the eleventh century and became known as “the Cathedral of the marshes”. After the Norman Conquest this church was used by monks and laity alike. By a miracle it did not fall victim to the bloody Reformation and has survived to this day as an active church more or less intact. Recent archaeological research shows that this church stands on the site of the first convent founded in about 670, and the present Benedictine Priory stands on the site of the monastery that was rebuilt in Minster later. St. Mary’s Church has a set of fine misericords which were used by monks in the medieval period when church services were very long (misericords are ledges projecting from the underside of hinged seats in choir stalls which, when the seat is turned up, give support to someone standing nearby). Among its other treasures are a very early tower and a small turret with ancient bells.

As we know, Minster much prospered under its first three abbesses: Domneva, Mildred, and Edburgh. The community of nuns lived a life dedicated to God, praised the Lord for His mercy, gathered in the church for prayer and services several times a day (including at nights), received and accommodated numerous pilgrims and guests, and cared for the sick in the infirmary. The convent also became a center of learning and had its own scriptorium for copying sacred texts and writings of the Church Fathers. The community increased and developed, and with it the local village grew, finally becoming a small port-town of local importance that even sent ships with grain to London. It was also recorded that not only did the convent support the mission of St. Boniface and other apostolic figures with gifts, but it also sent several of its own missionaries. Like nearly all early English monasteries, Minster was probably built of timber and wattle with roofs of thatch, though the main church after its rebuilding was of stone.

Unfortunately, Minster Abbey was many times attacked and plundered by the Danes, and its nuns each time had to take refuge in Canterbury during the raids. Such attacks continued for more than two centuries, from the 750s till the early eleventh century; in the ninth century, Minster produced its own martyrs. For some time from the tenth century on Minster belonged to the crown in order to protect the site for future religious life. From 1027 the site was administratively attached to the monastery in Canterbury. Soon after the Norman Conquest the building of the new (Catholic) monastery began in Minster, and from the twelfth century till the Reformation there was a monastic community of men there that was a sort of dependency of the Monastery of St. Augustine in Canterbury. Minster monks enlarged the main church, took pastoral care of the neighboring communities, and were involved in the construction of some eight more churches in the vicinity. The brethren preferred tireless manual labor, and farmed the soil themselves. The community had its own Norman tithe barn (where, as in many other monasteries, tithes in the form of grain were kept).

Minster Abbey

Minster Abbey At the time of the Reformation in about 1540 all the English monasteries, including Canterbury and Minster-in-Thanet, were dissolved. In Minster the abbey church was pulled down, while monastic and other buildings were either left derelict or transferred to the crown for secular uses of wealthy families. Nearly everything in Minster Abbey was finally destroyed, except for the west and north wings, of early English and Norman origin respectively, which are practically intact to this day. The whole estate of Minster was passed from one hand to another right until the twentieth century. In about 1930 the manor house with the adjacent territories of Minster were acquired by the Senior family. Soon archaeological investigations were carried out and foundations of the early English and Norman abbey churches were discovered, even the original location of St. Mildred’s shrine was found.

Finally, in March 1937 Minster was purchased by Catholic Benedictine nuns from St. Walburga’s Abbey in Eichstätt (Bavaria, South Germany) and reestablished as a monastic community for women. Thus, 400 years after its dissolution and 1270 years after its first foundation this holy site again became the home of monastic community and a place of monastic prayer and labors.

According to the Minster Chronicle (cited by the priory’s website), “Abbess Benedicta of Eichstätt, received the letter from Minster (with an offer to buy the property, which had been used for 400 years as a private house, for monastic use) on the same day as an officer of the SS demanded part of the abbey property for the use of Hitler’s “storm troops”. Abbess Benedicta saw the hand of providence in this coincidence and resolved to view the property.” The abbess fell in love with Minster from the moment she stepped on its land, saying that centuries of prayer left a great sense of peace. It was decided to buy the property, but under the Nazi regime it was impossible to take money out of the country. Fortunately, American foundations set up a trust and raised funds to buy Minster.

It was decided to dedicate the new convent to St. Mildred (all three holy women connected with the site are greatly venerated by the Minster sisters). In the first years of the convent, before and after the war, the sisters carried out all the hard work themselves: labored in the field, restored and rearranged the nunnery, sewed vestments for clergy, often limiting themselves to bare necessities of life or even managing without them, relying on God alone. In 1939 England entered the Second World War and the nuns who had come to Minster from Germany (as it was a risk for their lives) had to leave the nunnery and temporarily move to a Catholic convent in Devon, far in the southwest, where they felt safer. Late in 1944 the nuns returned to Minster-in-Thanet and monastic life resumed there. A true miracle happened in 1953: in that year a portion of the relics of St. Mildred, which for centuries had been kept in Deventer, Holland, was solemnly returned to England and enshrined in the Minster Convent. Since then popular and liturgical veneration of “the fairest lily of the English” was rapidly revived. An extensive rebuilding program was carried out in the following decades. Notably, the chapel to the Mother of God and the Apostle Andrew was opened in 1993. The precious relics of St. Mildred were placed inside it and are now available for veneration by pilgrims.

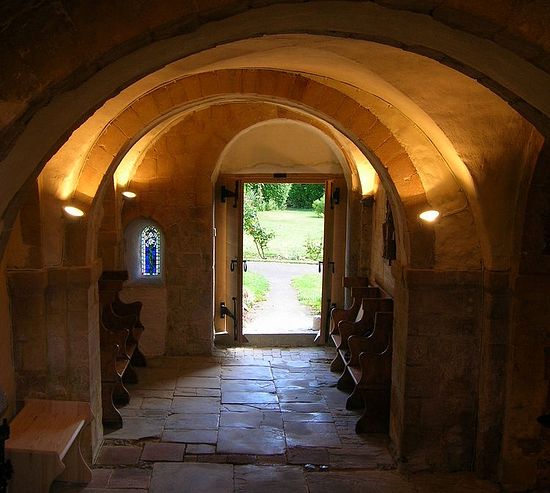

Minster crypt chapel (photo provided by Minster nuns)

Minster crypt chapel (photo provided by Minster nuns) For the first 70 years of its existence the community in Minster was dependent on the Bavarian Abbey of St. Walburga,2 but in 2006 it became an independent priory. Now the sisters of Minster-in-Thanet, apart from their hard monastic labors and prayers seven times a day, receive many pilgrims and guests (as it was under the three holy abbesses of Minster and their successors), arrange tours around the ancient holy site, which can boast of beautiful gardens and a park. A large and splendid carved image of St. Ermenburgh with her hind can be seen on the side of the abbey chapel. Among other remarkable relics surviving in the convent from the distant past we can mention the Norman great hall with an early vaulted passage, ruins of the massive medieval tower and a large carved image of Christ.

Ruined west tower in Minster (photo provided by Minster nuns)

Ruined west tower in Minster (photo provided by Minster nuns) To this day Minster-in-Thanet remains nearly the only ancient monastic settlement in England that has recently been reconverted for monastic life in modern times, despite the Reformation and consequent spiritual decline and secularism of our days. Today the community consists of thirteen nuns of various nationalities, and among the guests of St. Mildred’s Priory in Minster are Orthodox Christians.

Sisters in the Chapel of Our Lady and St. Andrew (photo provided by Minster nuns)

Sisters in the Chapel of Our Lady and St. Andrew (photo provided by Minster nuns) Conclusion

So we see three examples of holy women who were abbesses of Minster successively. St. Ermenburgh, who underwent many trials amid the political disputes in her married life in her young years, and had as the result of her sorrows the foundation of the great convent by the grace of God.

Sts. Domneva (Ermenburgh), Mildred, and Eadburga (Edburgh) - photo provided by Minster nuns

Sts. Domneva (Ermenburgh), Mildred, and Eadburga (Edburgh) - photo provided by Minster nuns Mildred was of a mild disposition, displayed kindness and concern to others and worked miracles. She indeed justified her name, which means “gentle strength”: as a person she was gentle and quiet on the one hand; but on the other hand her relics, veneration and even monastery outlived and overcame the Danish invasions, the Norman Conquest, the Reformation and the Nazis of the twentieth century. In ancient times Mildred was called “a white lily shining among roses”, “the pearl of Mercia”, and “the star of Albion”.

And there was the very talented and practical Edburgh, who encouraged missions overseas. All these nuns and those living after them were witnesses in quite difficult and unstable times, full of dangers and challenges, but in spite of everything they unceasingly glorified Christ, loved their neighbors and practiced hospitality and prayer.

Holy Mothers Ermenburgh, Mildred and Edburgh, pray to God for us!