Source: The Times of Israel

October 26, 2016

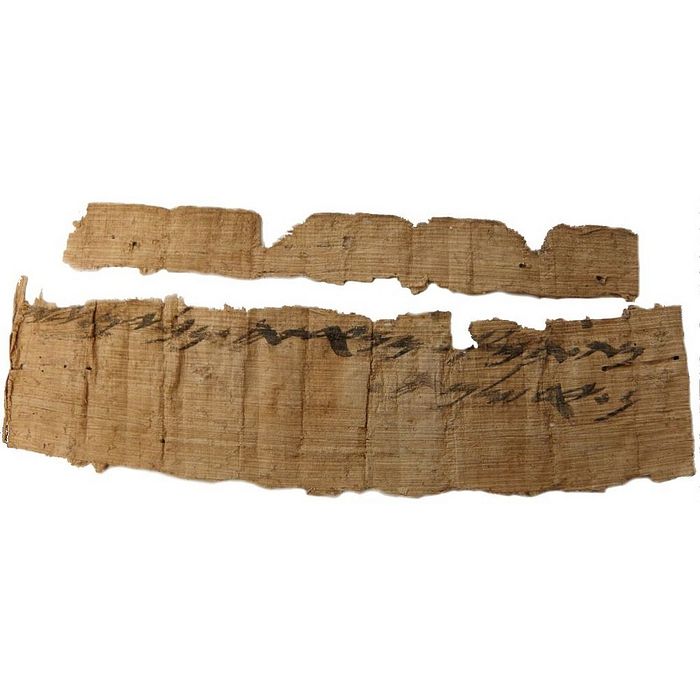

A rare, ancient papyrus dating to the First Temple Period — 2,700 years ago — has been found to bear the oldest known mention of Jerusalem in Hebrew.

The fragile text, believed plundered from a cave in the Judean Desert cave, was apparently acquired by a private individual several years ago. Radiocarbon dating has determined it is from the 7th century BCE, making it one of just three extant Hebrew papyri from that period, and predating the Dead Sea Scrolls by centuries.

The slip of papyrus, which was formally unveiled by the Israel Antiquities Authority on Wednesday, measures 11 centimeters by 2.5 centimeters (4.3 inches by 1 inch). Its two lines of jagged black paleo-Hebrew script appear to have been a dispatch note recording the delivery of two wineskins “to Jerusalem,” the Judean Kingdom’s capital city. The full text of the inscription reads: “From the female servant of the king, from Naharata (place near Jericho) two wineskins to Jerusalem.”

The fact that the note was written on papyrus, rather than cheaper clay ostraca, suggests the consignment of wineskins may have been sent to a person of high status.

Israel Prize-winning Biblical scholar Shmuel Ahituv arrives for a press conference to discuss an ancient papyrus featuring the earliest Hebrew mention of Jerusalem, October 26, 2016 (Courtesy)

Israel Prize-winning Biblical scholar Shmuel Ahituv arrives for a press conference to discuss an ancient papyrus featuring the earliest Hebrew mention of Jerusalem, October 26, 2016 (Courtesy)

Ahituv also said it was significant that the text features the “Yerushalem” spelling of the city’s name that is more commonly found in the Bible. There are only four instances in the bible, he noted, of Jerusalem being spelled “Yerushalayim,” with an additional letter Yod, the way it is pronounced in modern Hebrew.

Ahituv studied the papyrus after its acquisition by an individual who has requested anonymity.

Amir Ganor, head of the IAA’s antiquity theft prevention division, said the papyrus was determined to have come from a cave in Nahal Hever in the Judean Desert. The arid, cool location near the Dead Sea enabled the fragment’s preservation over the millennia.

The IAA’s Eitan Klein said the dating of the papyrus had been confirmed by comparing the text’s orthography with other texts from the period.

While there are more than a handful of ancient Hebrew texts etched into stone and scrawled on bits of pottery from this period, the only other known Hebrew papyrus texts from before the fall of the Judean Kingdom in 586 BCE were the Marzeah Papyrus, believed to be from mid-to-late 7th century BCE trans-Jordan, and a papyrus palimpsest found at Qumran.

The Israel Antiquities Authority has moved to prevent antiquities thieves plundering the country’s archaeological heritage, with particular emphasis on the limestone caves dotting the cliffs leading down to the Dead Sea. Those remote caverns have yielded two of the most significant collections of ancient Hebrew texts: the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Bar Kochba letters.

Stings in recent years have busted treasure hunters and traders in the act in Judean Desert caverns and Jerusalem hotels, while archaeologists race to excavate the area’s remaining caves in the hopes of discovering scientific data and, possibly, more scrolls.