See The Roman Trial of Christ, Part 1

Now let’s continue our lesson. This is part “b” of the Roman trial of Christ. Pilate was the governor of Judea for ten years, from AD 26 to 36, and this was a rather long time, considering that the length of a governor’s tenure was normally about two years, and we know also from historical records that Pilate was recalled to Rome to answer charges of cruelty and oppression because he had killed a large number of Samaritans. There is an actual record of this proceeding, and I went to look it up because I was so curious to see what happened. But the emperor Tiberius died in the middle of the proceedings, and because of this the case was dismissed, so he never actually was punished for any wrongdoing—there are various legends about what happened to Pilate. Eusebius of Caesarea, who was the first Church historian, tells us that he committed suicide, and there are some other legends with respect to Pilate. There is an Ethiopian tradition that he became a Christian and is a Saint in the Ethiopian church, but I think that’s extremely unlikely. We need to remember, dear brothers and sisters, that simply because something is “a tradition” doesn’t mean it’s true. There are various stories and legends about what happened to Pilate, but he seems to have simply faded into obscurity. Some people say that he died in Gaul in exile, but there’s really no clear understanding of what happened to Pilate. I think that Eusebius would know probably better than anyone what finally happened to Pilate, because he had a lot of historical sources available when he was writing his Church History. Eusebius is another one of those people, by the way, who is called a “Father of the Church” by the Catholics but isn’t by the Orthodox because he’s not a saint. He had tendencies toward Arianism, he believed in the Arian heresy—at least at one time—and this is why Eusebius of Caesarea is not a saint. But nonetheless, let’s continue talking about Christ and Pilate.

So Jesus was taken to Pilate, and as I told you, normally He would have been in the Roman city Caesarea Maritima and would have heard the case against Jesus or anyone else in a special room at the governor’s residence designated for hearing court cases. It was called an auditorium, and we still use that word, but that was where he would hear the case. You see that root word of hearing cases—auditorium. As the case was, he happened to be in Jerusalem for the Passover, living at the Antonia Fortress, and was just steps away from the Temple. Thus, it was very, very convenient for the Jewish leaders to be able to take Christ to him right away.

The King of the Jews

Now let’s return to what Matthew tells us about the trial in verse 11. “Now Jesus stood before the governor; and the governor asked him, ‘Are you the King of the Jews?’ Jesus said, ‘You have said so.’” Now, where does this come from? John tells us that obviously the Jewish leaders had told Pilate that Christ claimed to be the king of the Jews. This is really the charge against Him. This is now a political charge. So when they bring Him forward, they do not say, “He claimed to be the Son of God.” They must say something that is a violation of Roman law: “He claimed to be the King of the Jews.” Treason or sedition was one of the worst crimes in Roman law. The Romans were very paranoid about treason because they had a huge empire that they had to govern, and they were always on the lookout for people who might be a threat to Roman order. So this was a very easy charge to make.

Christ Himself, of course, had never claimed to be a king and never gave the slightest hint of political ambitions, but let’s start with the fact that Pilate questions Jesus. Now this is one of the powers that a governor had in connection with his right to dispense justice. This was called “cognitio”—judicial examination or inquiry. Cognitio was the way of handling a case that was different from specific procedures and penalties created by statute. If you were being tried for a specific crime, there were actual courts for specific kinds of crime. But this power of cognitio was very useful in the provinces, especially for people who were not citizens, because the governor was not restrained by specific procedures required by the law for certain kinds of crimes. And the judge, in this case the Roman governor, could relax penalties or aggravate penalties entirely at his discretion; so cognitio gave him wide latitude in which to prosecute the case.

Now it was routine, and even expected, that penalties and treatment of prisoners would vary according to their social status. People of low social status, poor people for example, were treated much more severely than people with wealth, position and power. In fact, status in the Roman Empire was everything. It was extremely important, and nobody would have said, “Oh, that’s not fair because you’re treating this poor person differently than the rich person.” They would have expected that. But also elasticity of the powers of cognitio gave the governor the right to dispense justice in what could be a very arbitrary and capricious manner.

Notice that Pilate does not ask Christ about threats against the Temple. He says, “Are you the king of the Jews?” Right? This is a political charge, a crime that carries the death penalty under Roman law. Chrysostom, of course, notices this also. Here is what Chrysostom has to say about it: “Do you see what He is first asked? For since they saw Pilate making no account of the matters of the law, they direct their accusation to the state charges. What did Christ say? 'You say so'. He confessed He was a king, but a heavenly king.” Notice that this manner of response is exactly like what Christ said to Caiaphas. Do you remember that? “You say so.” It is an affirmative answer just like what Chrysostom noticed here; it’s an affirmative answer. Chrysostom says, “He confessed He was a king, but a heavenly king,” and there, of course, he’s referring to the Gospel of John, where Christ tells Pilate that His Kingdom is not of this world.

Now, continuing with the quotation from Chrysostom. He says that, “Neither they nor this man should have an excuse for accusing Him of such things. And He gives a reason which cannot be refuted, saying, ‘If I were of this world, my servants would fight, that I should not be delivered’. For this purpose, I say, in order to refute this suspicion, He both paid tribute and commanded others to pay it, and when they would make Him a king, He fled.” Now there Chrysostom is reminding us that Christ had just told people you should pay the tax to Caesar—remember that? That was one of the ways that they tried to trap Christ, and that was in the Gospel reading of early Holy Week. Also, this reference to, “when they would make Him a king He fled,” is from John 6:15. After the feeding of the multitudes, the multiplication of the loaves, it tells us that the people wanted to seize Christ and make Him a king, and He fled into the mountains. So Chrysostom notes as he continues that, “For these reasons, because there was absolutely no evidence that Christ wanted to be considered a king, He did not reply but held His peace and answered only briefly so as not to have a reputation for arrogance from His continued silence, because He was not likely to persuade them.” That’s what he said in His homilies on Matthew. Chrysostom also notes that He was dispelling the fear Pilate had been entertaining that Christ had designs on power. And, of course, we know that there was nothing to suggest that He had any interest in political power.

More about the Roman judicial system

Now let’s look at the next verse, verse 12. “But when He was accused by the chief priests and the elders, He made no answer.” It says, “when He was accused by the chief priests and the elders.” So let’s take a moment and talk about accusers under Roman law. As I mentioned, there was no such thing as a police force, there was no such thing as a professional prosecutor, a state’s attorney, a district attorney, who would try the case in the name of the people. Instead, private citizens had to initiate actions to bring someone to justice. It could be the injured party, it could be an enemy of the accused, or even an anonymous accuser or informer—and you could see how this would lead to an abuse of the process. Normally, however, there was an accuser. Sometimes there were paid accusers, sometimes there were anonymous accusers; and accusations could easily be made by people with malicious intent, because if you allow, especially anonymous accusation or paid accusers, under such a system, without having state prosecutors, without people who were supposed to at least be impartial, without an interest in the outcome, you were likely to achieve a lot of injustice. And here, in the case of Christ, the accusers are present. They are the Jewish leaders, who make the accusations of the violation of crime. And since Christ is silent, they keep talking, and they’re saying everything they possibly can to try to convince Pilate that He has committed some kind of crime and deserves to die. It is also clear that they are motived by their own self-interests, and Matthew tells us straight out that Pilate knew that they had delivered Christ to him “out of envy.”

Now what’s the role of the judge in all of this? As the judicial system continued to develop during the imperial period of the Roman Empire, judges began to behave more and more as inquisitors. Even in cases where there was an accuser present to prosecute them, the powers of cognition allowed the governor to easily fall into a kind of situation in which he was the inquisitor, and he would assume a very active role in the trial as opposed to simply an judge or a praetor.

In the earlier period of the Roman republic there was a judge who presided solemnly and silently over jury trials. This is what the situation was during the Roman republic, but now in the provinces where we have the cognitio operating, we have the beginning of inquisition. In this case, Pilate is the judge, and he’s also asking the questions. He is, in a way, prosecuting the case. He’s asking questions, controlling the proceedings, questioning the parties, interrogating the witnesses, etc. So when you have someone who is engaged very actively in the proceedings, that means the person is usually less objective.

Now we also know that the defendant had a right to respond, and this is why Pilate asked Jesus, “Don’t you have anything to say about these accusations against you?” There was a burden of proof, and the burden of proof under Roman law was on the accuser. We see here that the Jewish leaders are losing because Pilate is not convinced that Jesus has done anything that was a crime, or certainly not deserving of death. So it was very important that the accusers make their case, and it was not uncommon that they would hire an advocate to argue or an orator to argue on their behalf, since their chance of success depended a lot on power of persuasion and rhetorical ability.

Now here, as in the Jewish trial, we see that Christ refuses to defend Himself. And of course, this is very much a fulfillment of prophecy. We remember this during the service of preparation, before the Divine Liturgy, when the priest prepares the bread and the wine to become the Body and Blood of Christ, and he’s preparing what is called the lamb—the center of the loaf of bread.[1] He says, “As a lamb he was led to the slaughter and opened not His mouth” (Isaiah 53:7). So the fact that Christ was silent continues to be remembered by the Church, that He refused to defend Himself. Nonetheless, Pilate was not persuaded by the arguments of the Jewish leaders, that He deserved death under Roman law, and he seems to be prepared to release Christ, and it was entirely within his power to do so.

Now when they would evaluate witnesses and demeanor, it was entirely within his discretion to consider the status of a witness, his behavior, the reputation, the general character of a witness. In Roman eyes, rich people were usually afforded much more latitude. Their testimony was considerable more reliable, more trustworthy than that of poor people. They assumed that the people would use all of their influence and their prestige and their power in order to sway the proceedings. In other words, they had no idea of fairness and impartiality regardless of one’s social status. Sо influence was expected to hold sway in Roman courts of law.

Pilate “wondered greatly”

So Pilate continues to ask Christ questions. In verse 13 it tells us, “Do you not hear how many things they testify against you?” Because the right to confront witnesses was a right accorded to people. The accused was allowed to speak on his own behalf or to have someone speak for him. He was allowed to respond to what the witnesses had to say against him. And there were no particular rules of evidence or custom. The witnesses could say whatever they wanted. They did not have to meet certain standards to prove the truthfulness of what they were saying, and sometimes the facts were completely irrelevant to the issue at hand. But as I said, the Lord remained silent, and it tells us that, “He gave Pilate no answer, not even to a single charge so that the governor wondered greatly.” I think that this is very striking, because Christ remained silent, just as He had in the trial before the Sanhedrin. I’m not at all surprised that the governor, as it says, “wondered greatly” in verse 14. I’m sure that Pilate was accustomed to defendants vigorously defending themselves, pleading for their lives, and Christ’s silence must have really perplexed him. St. John Chrysostom comments on this also. He says, “At these things the governor marveled, and indeed it was worthy of admiration to see Him showing such great forbearance and holding His peace—Him that had countless things to say. For neither did they accuse Him from knowing of any evil thing in Him, but from jealousy and envy only.”

Barabbas

Verse 15: “Now at the feast the governor was accustomed to release for the crowd any one prisoner whom they wanted.” Most likely what motivated Pilate to release a prisoner was not humanitarianism, but as I had mentioned before, Jerusalem had swelled during Passover to a very large population of extremely religious and zealous people who were remembering their deliverance from the bondage of slavery in Egypt. It was a good time to release a prisoner to let off a little bit of steam, show the great clemency of Rome, etc.

Now this particular detail that the Gospels agree upon, that Pilate released Barabbas instead of Jesus, that it was his custom to release a prisoner, has been attacked by people as historically inaccurate, because there doesn’t seem to be any evidence that the Romans had such a custom of releasing a prisoner. But what is interesting is that there are some Jewish sources that speak about the release of a prisoner during feast days (especially prior to the Passover) as being a Jewish custom. So I think it’s very possible that the Evangelists knew exactly what they were talking about, that it was a custom of the governor—not because it was a Roman custom, but because it was a Jewish custom. He was respecting and observing that custom. In this instance, it would have served Pilate’s purposes very well. He could bring in a few thousand troops to try to quell an uprising, but it would be very difficult against hundreds of thousands of Jews, so it was much better to try to placate the crowds by releasing a prisoner to them. Chrysostom had the following to say: “For he [that is, Pilate] wished that He should defend Himself and be acquitted, but since He [Christ] answered nothing, he [Pilate] devised yet another thing. It was a custom for them to release one of the condemned, and by this means he attempted to deliver Him. For if you are not willing to release Him as innocent, as guilty pardon Him for the feast’s sake. See how the order is reversed? For the petition on behalf of the condemned it was customary to be with the people, and the granting of it to be with the ruler; but now the contrary had come to pass and the ruler petitions the people.” Isn’t that an interesting observation Chrysostom makes? That normally, yes, the people petition for the release of a prisoner and the ruler grants it, but instead here we have the ruler suggesting the release and the people saying who will be released! A very insightful observation there.

Let’s go on to verse 16. “Now they had then a notorious prisoner called Barabbas.” St. John the Evangelist describes Barabbas as a “bandit” (John 18:40), but this does not mean that Barabbas was a simple highway robber. The same word, the Greek word lestes is used for revolutionary bandits or guerilla warriors, and Mark confirms this detail, that Barabbas was a revolutionary. Mark describes Barabbas as one of a group of prisoners who had committed a murder in an insurrection, and Matthew describes him as “notorious.” So Barabbas was very well known, possibly a leader of a gang of religious and political zealots intent on freeing the nation from Roman rule. So Pilate doesn’t really like the idea of releasing Barabbas because that’s exactly the kind of person who is a threat to Roman order.

Verses 17-19: “So when they had gathered, Pilate said to them, ‘Whom do you want me to release for you: Barabbas, or Jesus who is called Christ?’ For he knew that it was out of envy that they had delivered Him up. Besides, while he was sitting on the judgment seat, his wife sent word to him, ‘Have nothing to do with that righteous man, for I have suffered much over Him today in a dream.’” Now Pilate is already persuaded that Christ has committed no crime and that the motivations of the Jewish leaders are less than pure. He is really reluctant to take action and looks for some way out of this. He’s receiving a great deal of pressure from the Jewish leaders to convict Christ and to have Him executed.

Now you must remember that not only did the Jews have to cooperate, as Caiaphas had to cooperate with the Romans in order to keep his power, but also the Romans had to cooperate with the Jews and sometimes do the things that they didn’t particularly want to do to keep them happy. So he’s feeling the pressure here to convict Christ, he’s looking for some way out of this problem, and the message that he gets from his wife gives him yet another reason to try to distance himself from this case.

Pilate’s wife has been the subject of some speculation and there are a lot of traditions about her. Reportedly her name was Procula or Claudia, and she is considered a saint, however, there isn’t very much known about her. Nonetheless, I think there’s a little bit more to substantiate tradition about her having become a Christian rather than Pilate becoming one. There doesn’t seem to be any evidence that Pilate became a Christian.

Two different crowds

Verse 20: “Now the chief priests and the elders persuaded the people to ask for Barabbas and destroy Jesus.” Now this goes to what I have been talking about earlier when I told you about how ridiculous it is that certain preachers like to talk about the crowds, how fickle the crowds were—that on Palm Sunday they hailed Christ as the Messiah, but then on Friday those same people were shouting, “Crucify Him!” Here it’s obvious from the Gospels—and common sense would tell you—that this was not the same group of people. It tells us that the chief priests and the elders persuaded the people to ask for Barabbas, but it was more than that. They not only persuaded the people, they probably created the crowd. They generated the crowd itself to ensure that the crowd would ask for Barabbas. If it was a custom of Pilate to release a prisoner, the Jewish leaders would certainly know to assemble a crowd. They were the ones who knew that they were taking Christ before him, didn’t they? The ordinary population had no idea that this was even going on. They didn’t even know at this point that Christ had been arrested. Christ’s followers obviously knew, but the population at large did not know, and this was one of the busiest days of the year. It was the Eve of Passover. People were not paying attention to this.

They were busy getting ready for the feast.

Considering the popularity of Jesus it would not have been unlikely that they would want to make sure that Pilate would release Barabbas and not Jesus, and again, considering the fact that this is taking place very early in the morning on the Eve of Passover when people were distracted by other pursuits, other chores that they had to do prior to the start of the feast, it is extremely unlikely that there was simply a big crowd milling around outside the governor’s residence for no reason, a crowd of unbiased people who shouted suddenly, “Crucify Jesus!”. No, this was specially arranged by the Jewish leaders, otherwise it’s quite impossible to explain the crowd’s rejection of Christ now after they had adored Him and proclaimed Him the Messiah only a few days prior. It really doesn’t make sense to explain it in any other way, and of course we have the hints here from the Gospels which indicate that.

Verse 21: “The governor again said to them, ‘Which of the two do you want me to release for you?’ And they said, ‘Barabbas’.” The fact that the crowd shouted for Barabbas of course might indicate that his crime, murdering a Roman soldier, insurrection etc., was an act of patriotism. So it’s possible that there were people who really wanted to release Barabbas because he really was more of a Messiah figure than Jesus, since Jesus seemed to be a friend of the Romans. He was telling people to pay the Roman taxes, he cured the servant of the Centurion etc., and He had told people to turn the other cheek. But there was a great deal of meaning in the fact that the people cried for Barabbas, because the name “Barabbas” means “son of the Father”. “Bar”—son, and “abba”—father. So Barabbas has the name, “son of the Father”; and ironically the crowed chooses the one who bears the name, but the one who was not, in fact, the real Son of the Father.

Verse 22-23: “Pilate said to them, ‘Then what shall I do with Jesus who is called Christ?’ They all said, ‘Let him be crucified!’ And he said, ‘Why, what evil has he done?’ But they shouted all the more, ‘Let him be crucified!’” The Gospel of John provides more details about Christ’s appearance before Pilate. There Pilate states three times that he finds Jesus guilty of no crime, and he knows that Christ has not committed any crime nor is he a threat. And even the accusation of kingship is clearly understood by Pilate as metaphorical or spiritual when Jesus explains that His Kingdom is “not of this world,” and yet, the crowd will not be at peace. They are relentless. Pilate sees that he has no choice and he simply finds that in order to prevent a riot from breaking out, it tells us in verse 24, he decides to let them have their way.

“I wash my hands.”

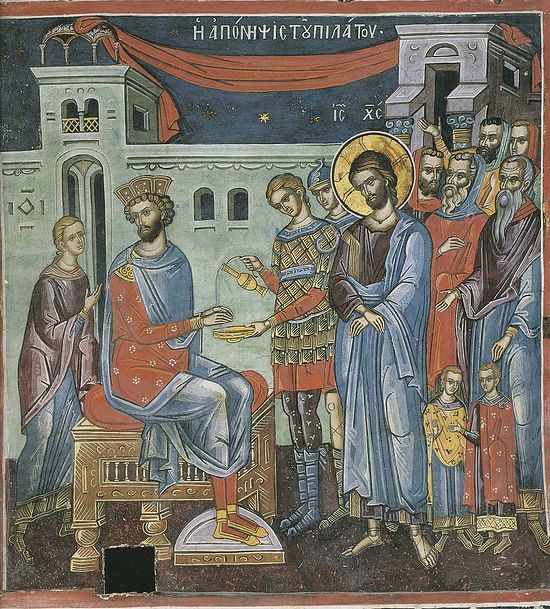

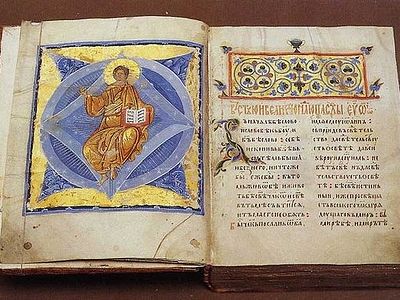

Christ Before Pilate. Pilate Washes His Hands. Fresco in the Church of St. Nicholas in Prilep, Macedonia. C. 1290.

Christ Before Pilate. Pilate Washes His Hands. Fresco in the Church of St. Nicholas in Prilep, Macedonia. C. 1290. Verse 24: “So when Pilate saw that he was gaining nothing, but rather that a riot was beginning, he took water and washed his hands before the crowd, saying, ‘I am innocent of this man’s blood; see to it yourselves.’” It’s quite ironic, I think, that Pilate washed his hands and considered himself innocent of the blood of Christ when after all he’s the one to whom we attribute the death of Christ. We mention His name every time we say the Creed, that Jesus was “crucified under Pontius Pilate.” So he remains responsible, ultimately, for the death of Christ. And Chrysostom said: “They themselves had brought Christ to him in order that the crucifixion might be the result of a verdict pronounced by the governor, but just the opposite happened; He was, rather, acquitted by the verdict of the governor.” Chrysostom knows the irony. They wanted Christ crucified, they (that is, the Jewish leaders) wanted to absolve themselves of responsibility for Christ’s death, but it is the governor who proclaims his innocence and puts the responsibility for his death back on the Jews. And of course, the entire purpose of releasing the prisoner was about to be thwarted. The idea was to prevent a riot or a rebellion, but since that is exactly about to occur because the crowd is insisting upon Barabbas, Pilate decides not to press the issue and instead gives the people Barabbas. I’m sure he did not want to do that.

St. Luke adds an interesting detail found only in his Gospel. When Pilate learned that Jesus was a Galilean, he found another way to try to avoid involvement in the case, and he sent Christ to Herod Antipas to be tried, because Herod had authority in Galilee, which was Jesus’ domicile. So even though the offense might have occurred in the different forum, that is Judea, which was under Pilate’s jurisdiction, Jesus was a citizen of Galilee. He was under the jurisdiction of Herod, so Pilate finds a way to try to absolve himself of any trouble with this case by sending Christ to Herod. But of course, Herod does nothing about it.

Now you mustn’t imagine that they took Jesus in the middle of the night all the way to Galilee–no. Herod was in his palace which was, again, a few steps away from here, near the Temple Mount, and he was there for the feast of Passover so it was easy to take Him there. But of course Herod did not want any part of this. He amused himself by asking questions of Jesus and asking Him to perform miracles, but Christ is silent. So when he is unable to have any fun at Christ’s expense, he simply mocks Him and returns the Lord to Pilate.

The “blood curse.”

So after Pilate washes his hands off the matter, the people respond in verse 25: “His blood be upon us and upon our children.” A very, very shocking statement, the famous “blood curse.” Chrysostom has this to say about that: “See here to their great madness! For be it that you curse yourselves, why do you draw down the curse upon your children also? Nevertheless, the lover of mankind, though they acted with so much madness both against themselves and against their children, so far from confirming their sentence upon their children, confirmed it not even on them, but from the one and from the other received those that repented and counts them worthy of good things beyond number. For indeed, Paul was one of them, and the thousands that believed in Jerusalem. And if some continued in their sin to themselves, let them impute their punishment.” That expression, “the lover of mankind”, or “the one who loves mankind,” is the word “philanthropos,” and that is a very, very typical way of referring to Christ in the Orthodox Church. So here it is translated as “the lover of mankind.” The one who loves mankind is Christ. And I think this is a beautiful insight which Chrysostom has, that Christ Himself did not accept the curse which they placed upon themselves and upon their children. So this “blood curse” should never be an excuse for anti-Semitism.

Unfortunately over the generations many people have used the trial of Christ to commit terrible acts against the Jewish people, to blame them for the death of Christ, to call them “Christ-killers.” This should never happen; and you see how Chrysostom is not an anti-Semite as he’s sometimes accused of being. He says that this curse was not accepted by Christ; instead, He forgave them. “The curse was not accepted or confirmed upon them, but He received those who repented and He counted them worthy of good things.” Chrysostom notes that Paul was one of the people who persecuted the Church of Christ and that there were many, many Jews who believed in Jerusalem. We must remember that all of the first believers were also Jews, and it is never acceptable to blame Jews, especially Jews today, for the death of Christ. This should never happen, and there is never an excuse for anti-Semitism, even though the Gospels have been abused by people and used to justify terrible acts against the Jewish people. This is very, very unfortunate, especially because many Jews today hate Christ because they identify Christ and Christians with persecution—and this is very unfortunate.

Roman flogging

Verse 26: “Then he released Barabbas, and having scourged Jesus, delivered Him to be crucified.” Now in John’s Gospel, Pilate had Christ scourged first before passing judgment, hoping that this terrible punishment might satisfy the Jews and avert the death penalty. Luke also confirms that Pilate believed that Jesus had done nothing to deserve death, and had Him scourged to as if “teach Him a lesson,” and then Pilate intended to release Him. This is what I was talking about, this is something different. The scourging is different from the flogging or the whipping that Christ might have received at the hands of the Jews. We’re going to talk about what a scourging was in our next lesson when we discuss the Crucifixion. But this came under another important tool of criminal justice under the governor’s power of what is called “coercitio,” which is the root word of our word “coercion.” You can see that the word coercitio was a governor’s right to force compliance or obedience without first engaging in the legal processes, so the governor’s power of coercitio gave him the right to beat people, to scourge them, imprison them, fine them or even execute them. It was called an extrajudicial power; it was distinct from his other powers, because it wasn’t used to punish a crime, but to force compliance or cooperation. This was one of the most important privileges of Roman citizenship, the freedom from coercitio, the freedom or the right not to be coerced. Not to be beaten or scourged or imprisoned without a trial, was one of the privileges of Roman citizenship. Not being a Roman citizen, Christ was not given this right to be free of coercitio, and instead He is scourged. Chrysostom says about this: “Having surrendered Himself over completely to the interests of this life, Pilate had no desire to do the right to the point of heroism, even though his wife’s dream must have terrified him greatly. On the contrary, nothing influenced him for the better, nor was he moved at all by unworldly considerations, but handed Christ over to them.”

Well, that concludes the Roman trial. Next time we will talk about the Crucifixion and all of the things it involved, and hear what the Fathers had to say, what spiritual insights they had to give us about the Crucifixion.

Now let’s say our closing prayer. “Lord, now let Thy servants depart in peace according to Thy word, for our eyes have seen Thy salvation which Thou hast prepared before the face of all peoples, a light to enlighten the Gentiles and the glory of Thy people Israel.” Amen.