The following is an excerpt from the English language version of Professor Alexei I. Osipov's book,The Search for Truth on the Path of Reason (Sretensky Monastery/Pokrov Press, 2009).

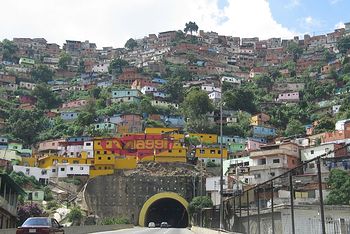

Caracas, Venezuela

Caracas, Venezuela

Our understanding of the source of the Orthodox view on social problems can be insufficient without first explaining other Christian points of view, first of all the Roman Catholic view prevalent during the Middle Ages, and the post-reformation view, which basically determined all recent history of European civilization.

S. N. Bulgakov assesses these two directions thus:

"The Middle Ages are directly opposed to more recent times, and yet they are very similar to each other, like the concave and convex of one and the same bas relief viewed from various angles. The Middle Ages stressed only Divine authority in life.… In their attempt to suppress, in the name of this Divine authority, human authority and man’s freedom, they fell into “holy satanism,” blasphemy against the Holy Spirit (for “where there is the Spirit of the Lord, there is freedom”). In more recent times, on the other hand, there is a one-sided reaction against Medieval mentality, a tendency to completely forget about Divine authority. Completely engulfed in an entirely human progress, [this age] borders upon godlessness, practically unrestrainedly sliding into pagan polytheism, naturalism, and idol worship.… The Middle Ages recognized an unearthly heaven, and made peace with the earth only as with an unavoidable evil. The latter times know for the most part only the earth, and that only for personal use; it only remembers heaven on holidays in church."[1]

By “Middle Ages” here Bulgakov means the era after the schism in 1054, when Catholicism’s loss of contact with the spiritual experience of the Ecumenical Church led to the appearance of extreme forms of asceticism.

The change from the Middle Ages to the new civilization happened on a religious basis and was conditioned first of all by the “Copernican” revolution of the Reformation in soteriology. If in Catholicism a person was supposed to be saved by bringing the appropriate satisfaction for his sins to God by good deeds, ascetic labors, and prayers, and receive what he has earned from Him, then the Reformation reduced the conditions for salvation to a minimum: neither deeds, nor prayers, and especially not asceticism, but faith and only faith saves a man. Man himself cannot do anything to save himself, inasmuch as faith itself, the only thing that saves a man, does not depend upon him, but only upon God. Man, in the words of Luther, is no more than a “pillar of salt,” a “block.”

Therefore, his salvation has nothing to do with his participation; there can be no talk of synergy; only God decides his fate. Thus, nothing is required from man for his salvation. A method was finally found to free us from any work on ourselves, from everything that is called asceticism in all religions. One can be saved, it turns out, without saving oneself [without laboring for one’s salvation]. There likely never was a greater “triumph of reason” in the history of religion.

This essentially changes the value of all the Christian’s secular activity, even his motivation for work. Instead of the Catholic understanding of work as punishment for the sin of our forefather (In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread [Gen 3:19]), and the means by which we redeem our sins from God, in Protestantism work becomes a free activity, directed only towards the satisfaction of earthly needs. For Christ already redeemed all the faithful from their sins; and for the faithful, sin is no longer accounted as sin. Work takes on a purely this-worldly value, to the exclusion of any eschatological significance. The energy of the spirit thus departing from Medieval man—energy which was earlier directed toward ascesis for the sake of salvation—is now completely freed up. All of his religious pathos was transferred from heaven to earth, from spiritual goals to everyday practical ones. The task of the Church as a society of believers is relegated essentially to social work from this point on.

The consequences of this soteriological revolution are entirely understandable: the borderline between life according to Christ and pagan life became even more indiscernible. The same S. Bulgakov wrote:

"Protestantism, as opposed to Medieval Catholicism, departs from the destruction in principle of any opposition between the ecclesiastical and secular or worldly. Worldly occupations, secular professions … are viewed as the fulfillment of religious duty, the sphere of which thus broadens to include all worldly activity."[2]

Any ordinary labor and, it follows, earthly life itself with all its values take on a sort of religious character for the faithful. There is a clear return to paganism with its cult of everything earthly. Theological, religious, and philosophical questions arise due to this, along with philosophical systems of thought based upon a new view of the meaning of human life, and man’s relationship to earthly activities. Materialism and atheism became the logical result of this process. The Protestant Church essentially turns into just one more charitable department of the government.

The concepts of an “unearthly heaven” and an “unspiritual earth” had different fates. The former, viewing the body as something contemptuous and any care for its needs as something approaching sinful, sank into the past. The second, for which material needs are not only the foremost, but in the final analysis, the only needs there are in the world, grew and developed rapidly during the modern era and is now marching triumphantly through the Christian world. The words of Christ—Seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness; and all these things shall be added unto you (Mt 6:33); These ought ye to have done, and not to leave the other undone (Mt 23:23)—are increasingly forgotten.

From the theological point of view, these positions could be characterized in Christological terminology as Monophysite and Nestorian, while the Orthodox point of view would be Chalcedonian. As we know, a referendum of the Fourth Ecumenical Council of 451 in Chalcedon determined that the Divine and human natures were joined in Christ “with no confusion, no change, no division, no separation.” The same Council also condemned the idea that Christ’s human nature is subsumed by His Divine nature (monophysitism), as well as the separation and autonomy of these two natures (nestorianism). In the context of the question at hand, this means that the one-sided spiritualism of the Middle Ages and the materialism of the Reformation are equally condemned. From this angle, the Chalcedonian dogma serves as a foundation for an Orthodox understanding of the nature of the Church’s social actions.

But how does the Church see itself as a subject of social action?

First of all, our attention is drawn to the paradox of sanctity and Divine truth abiding in the Church undivided and without confusion, on the one hand, and on the other, human sinfulness and mistakes. This requires an explanation.

The Church is essentially the unity in the Holy Spirit of all rational creation, following God’s will, and thus entering into the God-man Organism of Christ—His Body (cf. Eph. 1:23). Therefore, a Christian’s state of abiding in the Church is conditioned not only by the fact of his having received Baptism and other Sacraments, but also by his special communion with the Holy Spirit. All the Holy Fathers insist upon this.

In Baptism, the believer receives the seed of grace reborn by Christ in human nature, and thus also receives a real opportunity to begin growing spiritually. “Baptism,” writes Saint Ephraim the Syrian, “is only the pre-beginning of resurrection from hell.”[3] Saint Symeon the New Theologian explains, “He who has come to believe in the Son of God … repents … of his former sins and is cleansed of them in the Sacrament of Baptism. Then God the Word enters the one who is baptized as into the womb of the Ever Virgin, and abides in him like a seed.”[4]

That is, every baptized person partakes of the Spirit of God and abides in the Body of Christ only to the degree that he keeps the commandments and purifies his soul through repentance and humility. The Church itself abides in a Christian only to the extent that he allows space in himself for the Holy Spirit through the way he lives his life. Therefore, the degree of a believer’s participation in the Church and the character of his membership in it change continually, and his range of fluctuation can be very broad. The prayer of absolution read during the Sacrament of Confession over a member of the Church witnesses to this. It reads, “Make peace with him [her] and join him [her] to Thy Church.” The meaning of this prayer is understood. The member of the Church expels the Spirit of God from himself by his sins and falls away from the Church, the Body of Christ, but through repentance he once again partakes of the Holy Spirit and the Church. The measure of this return to the Church’s bosom is always relative; it is directly dependent upon the sincerity and depth of the Christian’s spiritual life.

But the Church is called a visible society (organization) of people, having a unity of faith, Sacraments, authority, and a ruling bishop. Its members are all those who have received baptism, even including those enemies of the Church who have simply not been excluded from it. That is, the image of any visible church always only partially corresponds to the Church’s First Image, for by far not all the baptized are true members of the Church—the Body of Christ; not all manifest and express its faith, or show themselves to be faithful witnesses and fulfillers of the truth preserved by it. This must be understood, for it is very pertinent to any discussion of social action in the Church.

The degree to which it [social action in the Church] is salvific proceeds entirely from an understanding of the two basic truths of Christian life, and mostly by the second commandment about love.[5] Nevertheless, the Christian understanding of love is by far not always the same as the generally accepted one. According to the Christian criteria, not every outwardly good deed is a testimony of love, or is actually good. That is, any benevolent or other social action in and of itself is not always an expression of Christian love. To put it another way, not everything considered good by worldly standards is actually good from the Christian point of view. What can prevent outwardly good deeds from being truly good?

The Lord looks at the hearts of men (cf. 1 Kgs 8:39) and not at their deeds. The Savior condemns those who do all their works … to be seen of men (Mt 23:5), and addresses these wrathful words to them: Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! because ye build the tombs of the prophets, and garnish the sepulchres of the righteous (Mt 23:29); But woe unto you, Pharisees! for ye tithe mint and rue and all manner of herbs, and pass over judgment and the love of God: these ought ye to have done, and not to leave the other undone (Lk 11:42).

The Holy Fathers call humility the supreme quality of Christian love, for humility is the foundation of its pure sacrificial nature, and its true unselfishness. According to the spiritual law revealed to the Fathers, there can never be even one true virtue where there is no humility. This first of all relates to the highest virtue, love. “If the supreme virtue, love,” writes Saint Tikhon of Zadonsk, “according to the words of the Apostle, is longsuffering, does not envy, is not puffed up, is not prone to wrath, and never fails, then this is because it is supported and assisted by humility.”[6] Therefore, Saint John the Prophet, a co-ascetic of Saint Barsanuphius the Great, said, “True [Christian] labor cannot be without humility, for labor by itself is vanity, and accounted as nothing.” [7]

The Holy Fathers teach most assuredly: good deeds are only those performed with Christian love, that is, with humility. Otherwise they lose their value, and even turn into evil; because, as the Apostle says, both sweet and bitter water cannot come from the same spring (cf. Jas 3:11). The spiritual law which the Savior Himself revealed to us also speaks about this: When the unclean spirit is gone out of a man, he walketh through dry places, seeking rest, and findeth none. Then he saith, I will return into my house from whence I came out; and when he is come, he findeth it empty, swept, and garnished. Then goeth he, and taketh with himself seven other spirits more wicked than himself, and they enter in and dwell there: and the last state of that man is worse than the first. Even so shall it be also unto this wicked generation (Mt 43–45).

According to the Fathers’ explanation of this passage, the soul that has been cleansed by Baptism but does not live as a Christian, and is not occupied by the spirit of love, becomes the abode of spirits more evil than those abiding in it before Baptism. That is why believers can be worse than pagans. This is caused by the ambition, pride, hypocrisy, and other passions that grow with particular fury in a Christian from an awareness of his importance, and deform his soul, turning his so-called good into an abomination before God. Jesus said to them, Ye are they which justify yourselves before men; but God knoweth your hearts: for that which is highly esteemed among men is abomination in the sight of God (Lk 16:15).

Saint Ignatius (Brianchaninov) clarifies it this way:

"Unfortunate is the man who is satisfied with his own human righteousness, for he has no need for Christ.[8] The doer of human righteousness is filled with self-opinion, high-mindedness, self-deception … he repays with hatred and revenge those who dare to utter even the most well-founded and well-intentioned contradiction of his truth. He considers himself worthy—most worthy—of rewards both earthly and heavenly."[9]

From the example of those outwardly righteous but spiritually rotten high priests, Pharisees, and scribes, we can see just what believers with a high opinion of their own worthiness and their service to God and people are capable of. They not only cast out the Savior, but sent Him to the cruelest execution. Apparently there is no question about how “pleasing to God” their social actions were. This illustration provides the key to understanding the activity of any Christian, and any Christian church.

Social action is performed by hierarchs, clergy, and laymen. Its Christian value can be quite varied. Their works can be the deeds of the Church only when they are performed not only by the decision of their superiors, but with Christian love, the presence and extent of which is hidden from people but clear to God, and directly conditioned upon the person’s spiritual and moral state. If Christians act for God’s sake, for the sake of fulfilling Christ’s commandment of love for neighbor, and have as their goal the acquisition of the Holy Spirit, then the Church works through them, and their works bring forth true fruits for both the benefactors and the needy. Saint Seraphim of Sarov said, “The true goal of our Christian life is the acquisition of the Holy Spirit of God … and every good deed done for the sake of Christ is a means for acquiring the Spirit of God.” He goes on to say, “Note that good deeds done for Christ’s sake will bring the fruits of the Holy Spirit.”[10]

As an example, we cite the following remarkable incident which occurred during Ivan the Terrible’s advance on Novgorod in 1570. Having sacked this city, he came to Pskov with the same intention.

In Pskov he met the fool-for-Christ, Nicholas Salos. Jumping onto a branch, Nicholas called out to Ivan the Terrible, saying, “Ivanushka, Ivanushka, come and eat (motioning toward the laden tables). Have some tea—you haven’t eaten enough human flesh in Novgorod.” Then he invited the Tsar to his tiny room, where a piece of raw meat lay upon a clean white tablecloth. “Eat, eat, Ivanushka,” he invited the Tsar, but the Tsar answered, “I am a Christian, and do not eat meat during the fast.” The fool-for-Christ then said to him angrily, “You don’t eat meat, but you drink human blood and have no fear of God’s judgment! Don’t touch us, traveler. Get out of here! If you touch anyone in God-preserved Pskov you’ll fall down dead—like your horse!” At that moment the Tsar’s stableman ran into the room, his face white as a sheet, and informed him that his favorite steed had died. The Tsar quickly left the city without touching a single citizen. Pskov was saved from the bloody horrors experienced in Novgorod. Such was the fruit of one Christian’s social work. This is the social work of a saint.

In contrast, social action can be taken by clergy and laypeople about whom the Lord said, This people draweth nigh unto me with their mouth, and honoureth me with their lips; but their heart is far from me. But in vain they do worship me, teaching for doctrines the commandments of men (Mt 15:8–9).

Needless to say, these people’s works, though they proceed from the highest ecclesiastical organs, have no Christian content beyond the form, and will bring no good. Even worse—such works often become a direct temptation for many, turning them away from Orthodoxy.

The idea that social activities performed by the Church are always and in all cases done according to the will of the Holy Spirit and do not depend upon the spiritual state, motives, or aims of those performing them, is seriously mistaken. The Church is both Divine and human. The actions of its visible members are only the actions of the Church—the Body of Christ—when they are done for God’s sake, and not for any other reasons. For wisdom will not enter into a malicious soul, nor dwell in a body subject to sins. For the Holy Spirit of discipline will flee from the deceitful, and will withdraw himself from thoughts that are without understanding, and he shall not abide when iniquity cometh in (Wis 1:4–5).

The spirit creates forms for itself. If baptized Christians remain pagans by their lives, then all their activities will be penetrated with pagan content and will in the final analysis be fruitless, even harmful, although they were done in the name of the Church; for God looks at man’s heart. There are plenty of motives for hypocritical good deeds and piety: seeking glory, riches, rank, approval from authorities, etc., and all those things that have often been hidden behind outwardly quite decent and benevolent social actions in the history of the Church.

At the present time, the character of many activities in Christian churches, especially in the West, testify to the steep drop in interest over matters of spiritual life, and a catastrophic sliding towards so-called “horizontal,” or to put it simply, purely worldly activity.

Very telling in this regard was the international conference of the World Council of Churches in Bangkok in 1973, on the theme, “Salvation Today.” Such a welcome theme this is. What more important topic is there for Christian discussion than that of the human soul’s eternal salvation? However, those few Orthodox participants, including those from the Russian Church, were deeply disappointed. Just about everything was discussed at this conference: social, political, economic, ecological, and all other problems of this life. The topic was salvation from various catastrophes: poverty, hunger, sickness, exploitation, illiteracy, aggression by trans-national corporations, and so on. The only salvation which was not discussed—the one for which our Lord Jesus Christ suffered on the Cross—was salvation from sin, from passions, from eternal damnation. Not a word was mentioned about this. The words of Alexei Khomyakov came to mind:

"There is a sort of deep falsehood in the union of religion with social concerns.… When The Church interferes in the discussion of bread rolls and oysters, and begins to put its greater or lesser capabilities of solving similar issues on display for all to see, thinking that it thereby witnesses to the presence of the Spirit of God in its bosom, it loses all right to peoples’ trust."[11]

There is no doubt that a Christian’s activities performed out of worldly motives do not lead to spiritual benefit and the evangelization of the world, but to the worldlification of the churches themselves.

This and similar worldlification in modern Christianity is a serious step in the direction of accepting the antichrist, for this false savior will solve (in any case, will create an appearance of solving) all the main social and other world problems. Thus, he will become the awaited christ for those so-called Christians who are seeking materialistic salvation today. Then unnoticeably, with Bible in hand, they will deny Christ the Savior.

Our Church has more than once expressed its criticism of such worldliness in Christian activity (“religious politicking,” as E. Trubetskoy put it). It has emphasized that the fundamental goal of the Church’s social service is to strive for spiritual and moral health in society, and not the growth of material well-being in and of itself. Saint Isaac the Syrian wrote, “With men, poverty is something loathsome; but with God, much more so is a soul whose heart is proud and whose mind is scornful. With men, wealth is honored; but with God, the soul that has come to humility.”[12] For the Holy Church, the words of Christ still show the way: Therefore I say to you, be not solicitous for your life, what you shall eat, nor for your body, what you shall put on. Is not the life more than the meat: and the body more than the raiment? (Mt 6:25).

Material prosperity, health, human rights, and so on, by themselves, without the acquisition of spiritual goods, do not make man better. Even worse—as the contemporary writer M. Antonov writes, “A person who no longer has need of material goods, but has never felt the need for spiritual development, is terrifying.”[13] He continues:

"Man is not a slave to needs and outward circumstances; he is a free being, but also a bodily being, and therefore he has to satisfy his needs and experience the influences of his environment. Apparently there exists a certain law of measure not yet formulated by science, according to which a person whose minimum requirements are satisfied is obligated to raise himself to a higher level of spiritual life, in order to avoid self-destruction. If this law is not observed, then material and fleshly requirements acquire hypertrophied proportions at the expense of spiritual essentials. Furthermore, this seems to apply to individual and society alike. The modern historical stage of Western countries, with the aggression in them of 'mass culture,' clearly proves the existence of such a situation."[14]

The modern psychological situation in the materially wealthy West is an illustration of this thinking. The Finnish Lutheran bishop K. Toyviainan summed up this situation:

"According to certain research, more than half the population of the West has lost its goal in life. We are convinced that the subject of psychiatrists’ work will be feelings of depression and despondency, to a much greater extent than suffering itself. A person’s motive for suicide is often his existential emptiness."

Social work in the Church can only be a service of the Church (and not purely secular activity) and bring spiritual good to people when it is based upon a sincere striving by its workers to fulfill the most important Gospel commandment, and thereby preach the name of Christ. The Apostle Paul wrote, And if I should distribute all my goods to feed the poor, and if I should deliver my body to be burned, and have not charity [love], it profiteth me nothing (1 Cor 13:3).

There are no reasons for social activity in the Church other than to preach Christian love, and turn each person to the path of salvation by teaching this love through word, example, and life. So let your light shine before men, that they may see your good works, and glorify your Father who is in heaven (Mt 5:16).