Tundra.

Tundra.

So I went there. Not alone though, but with my mother. It took me one hour and a half to get to the very eastern area centre of the district. The name of the area is quite simple—Chukotsky, it comes from the name of the region. Five thousand people, six villages scattered throughout the vast territory. Eighty per cent of the entire population are Chukchi natives. No plants, only one road that does not take you very far anyway—it only connects two villages of the area. To get to the mainland one needs a plane or a helicopter. All this place has is two seal farms and the infrastructure required for living. Almost a reservation, a pass is required to both enter and leave the place. My mother and I were looking through the window of the plane, below there was boundless tundra, lakes, rivers and hills. No one was waiting for us in Lavrentiya, no one invited us… We did not even know whether anyone needed us there. I asked my mom: “What are we going to do with Chukchi people? I have never dealt with them before”. My mother has worked for the Anadyr narcotics abuse clinic for many years, and she knew about the Chukchi from her life experience—not from books. She gave me a wise answer: “We are going to treat them to sweet tea, and they will like us.”

The local administration gave us the abandoned building of the former village council. Windows were knocked out, the roof was partially demolished, the heating system—just hopeless. We furnished a small room; now we use an oil heater, and conduct services. Only two people came to the service on the first feast day—the Transfiguration. On the feast of the Dormition, my mother and I were the only people at the services. But in September several people came—several women. I am beginning to understand the peculiarities of local life—it is summer, the time of vacations. Half of the Russian population of the village goes to the mainland for vacation, and the other half substitute for them. Most Chukchi people do not go anywhere, and do not come to church either.

So it is time to check my mother’s missionary technology—treat the Chukchi kids to tea and cookies (kav-kavka in Chukchi). They bring us boards, straighten nails, and help us in construction. They drink tea with great pleasure. There are several boys, and girls, their younger sisters. Their parents drink; the situation at home is just terrible, but they are cheerful and joyous just like all kids. We show a girl, Olesya, a children’s Bible and a picture depicting the Garden of Eden. She looks at palm trees and says: ‘grass, deep grass’. She calls a crocodile a rat; all other animals are dogs to her. She has never seen trees in her life. We turn a page and see the outcasts, Adam and Eve, warming themselves by the fire. Olesya’s eyes are showing more interest now. She asks why they were cast out. My mother thinks a minute and then answers—they got drunk with vodka, which is very bad, and that is why they were cast out! Olesya does not understand—her parents are always drunk, and their guests get drunk, too… Why is it bad? Well, it’s a real challenge to explain something like this!

We fixed the heating system in the church building, broke walls in three rooms that used to be offices, and made it into a worship room. Our main news is that Liuba came. She is a young lady, graduate of church choir school. She is so brave that she was not afraid to come here. She wants to see Chukotka and do something good in her life, sing the services in the middle of nowhere, and teach others to sing. It was such a gift for us! By winter more people started coming to worship, and we had around five people at the Sunday liturgies. We started Sunday school for the children who used to come for tea. Everything is almost the same, except for the moral teaching before tea, reading from the children’s Bible and a music lesson for dessert. Someone has donated a piano, so now during polar nights one can hear inspired singing coming from the church windows: “To verkhom, to peshkom po userdiyu, my idem k prepodobnomu Sergiyu…” (Meaning in English: “Both on horseback and on foot we zealously walk towards Saint Sergiy…”)

These words bring tears to one’s eyes and create the desire to go to the Lavra of St. Sergius. Also, we would like to believe that there, in the Kingdom of Heaven, father Roman[1] hears the Chukchi children singing his song. They sing it with such inspiration, even though they never saw the Lavra, neither do they know who Saint Sergiy is. The meaning of the lyrics is not clear to them but, they feel it is something good and pure. I try to tell them the Lives of Saints, then look in their eyes and realize—it is useless. So we start learning something they would understand—a beautiful song about the local land:

“Inogda ot lyudey ya slyshu (Sometimes I hear from

people),

Chto u nas ne zhit’e, a gore (That our life is

nothing but sorrows),

Zlye vetry sryvayut kryshi (Wicked winds tear off

roofs),

Postoyanno bushuet more (And the sea rages all the

time)…”

This poetic and true description of the advantages and disadvantages of Chukchi life ends with the following words:

“Inogda ot lyudey ya slyshu (Sometimes I hear from

people),

Budto zhizn’ u nas bez prosveta (That our life has

no hope),

No my znaem zemlyak s toboyu (But, brother, you and I

know),

Chto ne pravda, ne pravda eto (That it is not true, not

true at all).”

The history of our Sunday school is not rich in educational victories. Chukchi kids are dirty, constantly hungry, all have lice, wearing old worn clothes. In winter they go around in light jackets… In both seminary and academy we were taught everything but how to organize a Sunday school. But even if they had taught us this, I do not think that knowledge could help me in such specific environment.

Half of the problem is that children come from families of alcoholics, and because of this they have some developmental delay. It is not surprising that they have difficulty focusing on subjects, have no skills of assiduity and diligence, and are only interested in games and cartoons. All education is brought to nothing by their everyday life, their families and friends—all completely opposite of what we teach them. Conceived in drunkenness, born in drunkenness, grown up in an atmosphere of irresponsibility and indifference… Souls crippled from their very infancy. It was very difficult to understand them and get used to the fact that these children had entirely a different psychology; they came from a different world, a different life to which we had no access, and absolutely no desire to enter.

Here is an example. Two twelve-year-old girls became witnesses to a murder. Drunken men tortured and killed a boy of their age, their relative, before their very eyes. Then they took the body outside and hid it in a snow pile by the house. What is most surprising is not that they did not tell anyone about this, even though a thorough investigation was conducted. What is most surprising is that no psychological trauma was noticeable in them. They kept coming to our classes; they sang, laughed and had fun just like before. Only a few months later one of them betrayed herself when speaking to a friend, so the crime was revealed. When I asked girls why they were silent about this, they answered simple-mindedly: “No one intimidated us. The guys just told us to keep silence, so we did”.

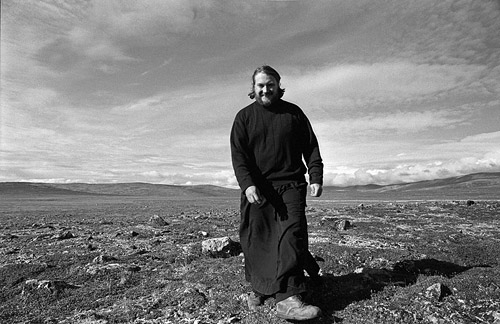

Fr. Leonid and his mother.

Fr. Leonid and his mother.

We were dreaming about the next Christmas. We thought we would go all over the village in dog-drawn sledges, with jingle-bells and stars, and praise Christ. Unfortunately, the next year there were different kids in our school, and different songs, too. Every group of our Sunday school normally united around the leader, who would bring his friends there. And leaders would leave us, sooner or later. Usually the reason was the same each time—stealing. It is our headache and major problem in relations with children. It was difficult and unusual to live in constant tension, cautious. Did someone steal money from a purse left in a pocket? Where is the tin of condensed milk that was in the refrigerator, or a bottle of Kagor wine from the offering table?

At times, constant suspicion would grow into a mania, and I would think sadly, “What kind of circus is this? Everything lost its meaning a long time ago… it is not a temple but a den of thieves. The right thing would be to kick everybody out.” But if we kicked our students out right away without giving them a second chance (sometimes event third, fourth or fifth chance) we would not have a Sunday school. We had to tell some to leave, some would leave by of their own accord after another recurrence, and some would just grow up and lose interest. Only during the fifth year of the Sunday school’s existence did the third group begin learning and memorizing things, doing dishes; and, what’s most important, these kids deserved our credibility.

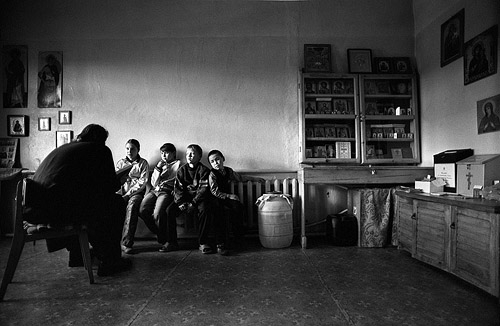

A very comforting scene.

Every winter, on Theophany, our congregation would go to the Lorinsky thermal springs. We would order a local bus—a URAL truck with a cabin for people. About forty parishioners, children, and just friends would get together, serve a greater blessing of the waters, and bathe in the hot water.

On one such holiday, in the morning, during the liturgy, the weather started getting worse. Strong winds made the snow drift; on top of that, the temperature was more than thirty degrees below zero, Celsius. The bus came to the church building but there were only were five parishioners there. The weather kept getting worse, so we almost decided not to go, and bless the waters inside the church building instead. It was sad—the holiday did not look like a holiday any longer. But then a crowd of kids covered with snow burst into the building—all students of our Sunday school. They looked at me with such joyous anticipation that we had no choice. It was quite dangerous and a great responsibility to cover thirty kilometers of tundra in a blizzard, but we went anyway. There were five adults and twelve children along.

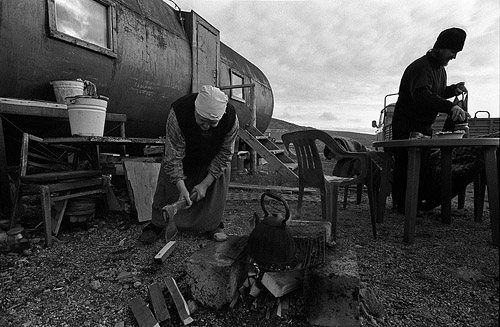

At the thermal springs.

At the thermal springs.

Of course, at the time I had no doubt that the time and strength we spent for these kids was to good purpose. Only God knows whether they will make the most of our relationship, whether our classes and tea will influence their life in the future, whether good seeds will be rooted in their souls and bring fruit. I doubt that we will be able to change their life essentially; it seems to be too hard and hopeless. But they did help us, for sure. They helped us not to become disheartened. In this isolated, drunken, Chukchi village, they were our support. Well, perhaps we did not teach them much, but we treated them to tea. And it was pleasing to God; I have no doubt about this.

I was the only priest for four districts.

So, I began traveling through Chukotka. Summer 2002. Huge distances, the only transportation is aircraft. Lavrentiya, Providence, Egvekinot, Cape Schmidt, and other settlements. Every area center has a congregation and premises for worship.

In Providence, church meets in a former pharmacy building, in Egvekinot, services are held "in a secular way," in a redesigned two-room apartment. I received a warm welcome—for local Orthodox people, a priest is a rare and dear guest. Normally, for the first few days, many people come to confess, take communion, or be baptized. They ask me to bless their apartments, or invite me to a school or hospital. But after three days they become less active, fewer people come to church; the few people that come are regular parishioners. Three more days and you understand that the religious needs of the settlement have been met for a month or two, so it is time to go home.

It is nice to come to such parishes—people meet you, find a place for you, feed you, and see you off. It is even possible to collect some money for tickets. If you take scheduled flights, each trip costs at least ten thousand rubles. If weather is bad and flights get cancelled, you can wait for a week or two in relative psychological comfort. You can serve, read books, and walk in the neighborhood… There may be few parishioners, but they all are Orthodox, they love and respect you.

It is entirely different at the ethnic, pagan, Chukchi settlements. There are few or no Russians there. For the first three days, you just walk around the village; all the people stare at you and treat you like an alien—a priest has come! Chukchi children stare at you with surprise and ask, “Who are you? God? Then why are you wearing a skirt?” Drunken adults cling to you in the street, cross themselves in the wrong way (from left to right) and ask with a faltering tongue: “How can we… well… What do people do in your church? Get baptized, or something like that?”

God’s protection from evil forces is something every Chukchi understands. No one has doubts about the existence of spirits in the tundra. No one usually questions the fact that there is one God, and that He is the One to ask for help. They willingly bring their children to have them baptized, even though the adults themselves rarely proceed to this sacrament. I do not seek to baptize adults either, when I see that they are not ready to become Christians, and that their life is not going to change. The main task of my coming to such village is to let people get used to me, to convince them that I did not come to destroy their traditions and way of life, and that I am not going to force anything on them. It is very important that people be ready to listen, and not be aggressive towards you.

Before leaving, I usually try to serve a liturgy, most often in order to do this I have to ask for a room in the local club. I give Communion to children and adults who show deep interest. I do not look at the clock during services. I read the books of the Epistles and Gospel in Russian, because in such an environment Church Slavonic is taken as something entirely foreign. Russian people, even if they are far from the Church, show respect for the language of worship, take it as something sacred, given to them by ancestors, as a perhaps little understood, yet important part of their own culture. Chukchi people simply do not understand it, and show no reverence for it.

It is not realistic to serve an All-night Vigil in such villages. All that can be done is prayer services and short requiems, the rest should be prayed in simple words. It is very difficult to work in such places. It is difficult because the standard patterns of a priest’s conduct do not work here. I was ready to give them what most people need—services, confession, conversations about problems. But these things interest them least of all. What is needed here is a demonstration of faith in all its depth and simplicity, in clear words and specific deeds. There is no use in missionary trips, baptisms and sermons if you just go away afterwards and leave everybody at a loss.

The seeds of faith will only come up and give real fruit if an Orthodox congregation is formed. And the congregation will only be established if there is a person who can unite all these people. A priest has to go to all corners of this huge territory, so he can only come to each village two times a year at best. So I doubt that the priest can become that person.

The more experience I was getting in these trips, the more humble I was becoming. Sometimes I would meet all locals and baptize about sixty people… At times many people would come to a service, or I would go to school and speak long with both students and teachers, which made me feel good. I would do "the whole program" and leave feeling satisfied. Six months later, I would come to this village again and it would look as though all was in vain. The only good thing is that they greet me like someone they know.

Then I understood that there had been no success at all, since people do not care. Quality "work" is not enough here. One must live here; this is a place where podvig is required. This is where one can truly understand Christ’s words, Without Me, ye can do nothing—with your whole heart and not just with the mind. If you achieve any results here at all, they are normally through a miracle, and require almost no participation from a priest.

An amazing example of the above-mentioned.

An amazing example of the above-mentioned is how the Orthodox congregation in Enmelen village was started. I suppose this is the only case when a village congregation consisting of Chukchi people did not fall apart right after it was created. It is still healthy, in spite of almost complete isolation.

Zoya Oreshkina, director of the only store in Enmelen, lost 300,000 rubles. The sale proceeds for a month just disappeared as she was travelling in a cross-country vehicle, in the tundra. She was taking it to the area center, Providence. An incredible incident… Where could money disappear in the tundra? No one believed her so the woman was accused of embezzlement, and an investigation started. Out of despair, an ardent pagan who had never cared for Christianity came to church. This is where I met her.

What could be done in this situation? We had a prayer service, lit candles and prayed in our own words. The next day, the money was found. It turned out that an eight-year old boy who was in the same vehicle had stolen it. No one even suspected him. After this, Zoya was baptized, and went home happy. Two months later, when I went to Providence again, she called me to invite me to Enmelen.

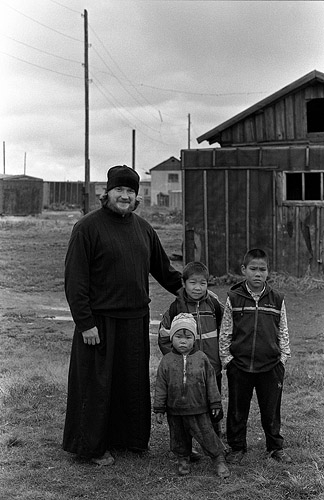

Fr. Leonid with children in Lavrentiya, Chukotka, Russia.

Fr. Leonid with children in Lavrentiya, Chukotka, Russia.

There was a congregation of Pentecostals in Enmelen, so almost all the people who started coming to Zoya’s had been to Protestant worship services at least once. Some had attended those services for quite a long time. Our parishioners successfully borrowed some elements of Protestant worship. Women would read akathists and canons from the prayer book, the Bible, and Lives of Saints, and drank tea. They also prayed for different needs when they could find appropriate prayers in Slavonic, and when they could not find them they used their own words. Every time I came, we would have a Liturgy; everyone would confess and take communion. During evening services, every one present had to read out loud at least one prayer. During Sunday worship services, the small room in Zoya’s house was packed. Adults would crowd around a small table that served an altar. Kids played in the back row, on the couch, and every now and then, cried and acted up. Ubiquitous dogs tried to get in the middle, barked and howled with indignation, and bit the legs that did not let them get in the middle. It looked unusual, but my heart greatly rejoiced! I cannot find appropriate words to describe how comforted I felt!

I tried to come to Enmelen as often as possible, at least four times a year, especially in the beginning. Every trip would take from three to six weeks. Most of this time I had to spend in Providence while waiting for a helicopter or a cross-country car going my way. Time and again I would stop at other villages of the area (Chaplino, Noonligran, Sireniki) but nothing could compare with Enmelen.

The Providence area had been actively worked by Pentecostal and charismatic missionaries. In every settlement, they started their congregations long before the Orthodox did. What was almost a miracle to us was a usual thing to them. Preachers did not at first start congregations in small villages; they just selected the right local candidates and sent dozens of them to their Christian centers (usually located in neighboring Alaska) for education. As a result, one out of ten managed to go back to their home village and start a viable congregation there. Of course, it was easier for charismatic missionaries than for the Orthodox. This denomination seemed to be created for Chukchi since it complied well with the deep archetypes of their religious consciousness, rooted in shamanism. I think we should adopt the best of their organizational experience, even more so if life itself is telling us this is the right thing to do.

There are many other things I would like to tell you about—missionary groups of students and priests of Moscow Theological Seminary and choristers, who visited our settlement three consecutive years. About their concerts, or the places they visited. About the development of our parish in Lavrentiya, or about our amazing pilgrimage (the first and only in the history of our diocese) to the cross at Dezhneva Cape.[2] About the only sponsor who has been helping our parish all these years—the Swiss charity foundation, "Faith in the Second World." But it is impossible to tell everything—readers will grow tired of so much information. So I am ending the story with a thought that is dear to me, even though it is not new: In real life, missionary work in remote areas boils down to the most important thing—one must survive as a Christian. One must not fall or become degraded, not quench the light of his faith, and not become an alcoholic. The Lord Himself will add the rest to our weakness.

Courtesy of Noga Art