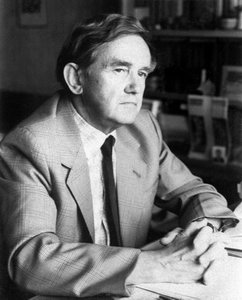

The author of this article published

in the Journal of the Moscow

Patriarchate in 1993, Andrei

Cheslavovich Kozarzhevsky, was born in Moscow in

1918. From 1924 to 1936 he was an altar attendant and

then a reader at the Church of St. Elias the Prophet

in Obydensky Lane, Moscow, and a spiritual son of Fr.

Vitaly Lukashevich, rector of this church, who died

in an Ussuri prisoners' camp in

1938.[1]

From 1958 to the end of his life, Andrei

Kozarzhevsky taught at the faculty of Ancient Languages

at Moscow University, and was appointed chairman of

that department in 1967. He authored many works on

religious themes, in particular, on the sources of

early Christian literature, and translated works by the

holy fathers. One of the themes of his scholarly

research is history of parish life in Moscow. He

delivered lectures on Moscow churches, monasteries and

church life at the Znaniye (Knowledge) and Staraya

Moskva (Old Moscow) societies, the Cultural Foundation,

the All-Russia Society for the Protection of Monuments

of History and Culture, and at various educational

establishments, including the Moscow Theological

Academy. Andrei Cheslavovich Kozarzhevsky departed this

life on March 26, 1995.

Andrei Cheslavovich Kozarzhevsky.

* * *

Whenever the theme of the Church’s position during the first two Soviet decades is discussed, attention is usually concentrated on the tragic side of her life; thus parish life, the life of ordinary worshippers, pastoral activity (Fr. Alexiy Mechev perhaps being the only clergyman given scholarly attention), and traditions which have already become a thing of the past, unfortunately escape researchers' attention. All this is preserved in reminiscences of old parishioners, whose number is naturally and inexorably depleting.

However, the theme of repressions against the Church, the aggressive state-encouraged atheism, the role of the Obnovlentsy (Renovationists) cannot be avoided here, either. Our insecure, troubled life is not guaranteed against a recurrence—even if on a different scale and in different forms—of evil doings of the past.

To what can we, ordinary parishioners who do not know the whole truth about the crimes perpetrated against the Church, testify as eye-witnesses?

Naturally, I cannot remember what was experienced by our fathers and grandfathers during the first few years of my life: brutal killings of clergymen, desecration of churches, the opening up of relics, plunder of church valuables on the pretext of raising funds for famine-stricken people, deportation and exile of religious thinkers, the persecution of His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon and his premature death. I learned about all this later from my relatives and friends.

My generation witnessed the second wave, which began in the year 1929 ("the year of the great change", as it was called by the Soviet press). This involved mass exiles, arrests and executions of clergymen. My godfather, Archpriest Ilya Zotikov, was an associate of His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon. Prior to his arrest, Fr. Ilya was the rector of the Holy Spirit Church at Prechistenskiye Gate (in Soviet times called Kropotkinskiye Gate). Serving in this church together with Fr. Ilya was a deacon, Fr. Mikhail Astrov,[2] a man remarkable for his Christian conviction and devotion to the Church. He would seat me on his lap and initiate me into the fundamentals of Orthodox catechism. In the late 1920s, when I was still a little boy, I assisted Fr. Ilya who served in a cemetery church in the city of Vladimir, which, after the closure of the Dormition Cathedral, served as the cathedral church of the Vladimir diocese. Together with other clergymen, including Archdeacon Konstantin Lebedev, Fr. Ilya was sent to the Vladimir prison, notorious for its brutal regime. Fr. Ilya died of a heart attack on the way to the place of his execution.

Priests

and other clergymen—so-called "servers of

the cult" who survived repressions, were not

only disenfranchised, but deprived of food ration

cards. Of course, the faithful did all they could to

save their pastors from starvation. Churches were

being closed down and destroyed before my very eyes.

Here are just a few statistics which are probably

already known to the reader: in 1917 there were some

700 churches on the territory within Moscow’s

present motor ring road. By the beginning of World

War II, half of them had been torn down, an

insignificant part had been turned into museums, and

only some 40 churches continued to function. The rest

of the churches, reduced to a pitiful state, housed

various enterprises, establishments and

warehouses.

Fr. Vitaly Lukashevich

I remember the destruction of the Cathedral Church of Christ the Savior, which was situated opposite my house. Its demolition was preceded by an unbridled campaign in the press, which some scientists, even art scholars, were not ashamed to take part in, especially since at that time the Byzantine-Russian style of the mid-19th century was almost considered a failure in the development of Russian architecture.

Recently I saw a newsreel about the destruction of the Cathedral Church of Christ the Savior, as well as some other churches. I was literally thrown off balance by the merry mischief with which workers and hired peasants destroyed the cathedral and the nearby Church of the Laudation of the Mother of God, by the jauntiness with which women no longer young, their eyes undimmed by tears, took out icons and threw them into a bonfire. Very often people explain all of this by some dark, directing force. But what about the people themselves? It is quite unlikely that in 1917 they suddenly became atheists en masse as if on somebody's orders. Consequently, prior to the revolution neither the government nor even the Church—and this is emphasized by Archbishop Luka Voino-Yasenetsky (†1961) in his diaries—showed due concern for the religious education of people. In his famous "Letter to N. Gogol", Vissarion Belinsky wrote with bitterness about our superficial religiosity. Poet M. Voloshin was also quite right when he said in his poem, "The Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God", that during that wrathful time, some people themselves gave up the keys to their shrines, and the Virgin Protectress left Her desecrated strongholds. I remember that people not only burned icons, but also used them as boards, that they wrapped herrings in beautifully ornamented Gospel pages, wore capsmade of Church vestments; chapels were turned into lavatories... But against the dark background of the mass apostasy, new martyrs, whose blood washed the Russian Orthodox Church, shine all the more bright, like stars.

Monstrous

taxes were imposed on surviving churches. Before the

reading of the six psalms at matins, a church rector

wearing his epitrachelion would come out onto the

ambo, bow to parishioners, explain the situation, ask

for help, and then take a plate and go around the

church collectings donations himself. A strict state

control was imposed on the performance of all church

offices. By far not all people ventured to baptize an

infant, celebrate a wedding, or order a funeral

service: "bold spirits" ran the risk of

being sacked. In order to hold a wedding

ceremony, for example, special precautions

were taken: they closed the outer window shutters and

switched off the light in the vestibule through which

the bride and the bridegroom stealthily entered the

church. On Easter, hooligans were sent to churches;

they whistled, swore and rocked the tightly packed

crowd of worshippers. Amplifiers were installed near

churches to muffle church singing with the thunder of

vulgar music. Chinese students from the Communist

University of Oriental Peoples burst into the

Cathedral of Christ the Savior, extinguished lampadas

and candles, and, using great inventiveness and

assiduity, put small paper balls into candlesticks to

prevent worshippers from placing candles in

them.

Church of Christ the Saviour and the Church of the Laudation of the Theotokos in Bashmakovo

In 1930, bell ringing was banned in Moscow, and bells began to be thrown down from churches. I think I still hear the moan of bells being broken. The Vorobyovy Hills were then located outside the city boundary, which ran along the circular railway, and Muscovites used to go there to listen to the ringing of bells in the modest Trinity Church before this tradition became a taboo everywhere.

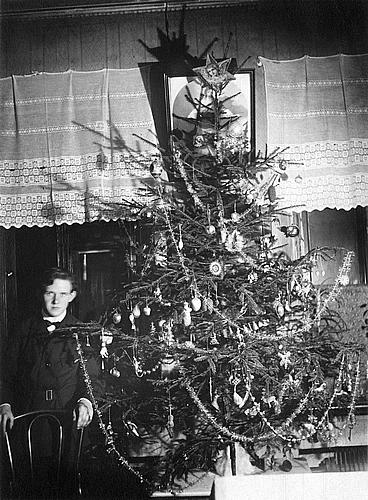

There was a time when Christmas-trees were also prohibited, and people had to decorate them behind carefully drawn blinds, lest the "politically conscious" (those who broke off with religion were called "people who came to know what's what") should inform the authorities.

In

childhood I used to go to church on the sly, taking

every precaution; boys from our yard nicknamed me

"priest"; they lay in wait, beat me and

threw bricks at me behind my back. In the school I

attended, they set up a board with the names written

on it of the pupils who dared to miss lessons on

Orthodox feasts (if a church feast fell on Sunday,

that day was proclaimed a working day).

Andrei Kozarzhevsky, age 2.

My childish soul was particularly badly wounded by the unbridled anti-religious campaign, which was usually stepped up on the eve of church feasts. Spasms contracted my throat when quite by chance (I did my best to avoid this) I saw in the magazine Bezbozhnik (Atheist) or on a fence, caricatures ridiculing the images in front of which lampadas burned in the right corner of our home, images which were infinitely dear to the heart—the meek sufferer Christ, the kind and sad Mother of God, the always helpful and yet stern St. Nicholas. I have retained for the rest of my life the almost physically intolerant attitude to Moor's drawings and Demyan Bedny's poems.

Strange as it may seem, but a few years ago, when this country witnessed the beginning of the revival of spirituality and normalization of relations between the Church and the state, on somebody's initiative the Sovetsky Khudozhnik (Soviet Artist) Publishing House brought out an album of anti-religious caricatures of the 1920s-1930s.

The anti-religious shows staged during October and May Day demonstrations were disgusting. Dressed in real church vestments and wearing attachable red noses and wigs, young people represented priests and yelled obscene ditties.

I was lucky: my parents managed to

teach me the fundamentals of catechism and

Church Slavonic, to accustom me to constantly read

the Gospel and the Lives

of saints. Later, when I was a high school

student and then a college student, I saw in our

library rules (as far as I remember, it was in

paragraph 14) religious books and pornography

grouped in the same paragraph of prohibited

literature. Thus, for many decades people were barred

from reading "the book of books", the

Bible, let alone Church literature. That is why, in

spite of their higher education, people of my age

often lack what in civilized countries is viewed as

elementary knowledge. One can hardly believe now

how difficult it was to buy a little cross or

miniature icon at that time.

Kozarzhevsky with a Christmas tree.

I cannot remember, of course, how the Renovationits movement came into being, but I was an eye-witness of its development. I shall abstain from describing the so-called "red Church" and her ideological leader, the self-styled metropolitan, "apologist and preacher of Christ's truth", A. Vvedensky—a lot has already been written about it.[3] The Moscow authorities confiscated the Cathedral of Christ the Savior and other churches, first of all cemetery churches, from the Patriarchate and turned them over to the Renovationists. Prior to this, as I vaguely remember, my mother and I attended one divine service in the overcrowded Cathedral of Christ the Savior. We stood with candles in our hands in the gallery, by the marble plaques bearing the names of heroes of the War of 1812. I cannot say for sure what day it was—Palm Saturday or Holy Thursday, but it was a patriarchal service, I think. It was considered a sin to visit the church that had come into in the hands of the schismatics and so, walking in the nearby garden, I was just watching from afar how A. Vvedensky arrived at the cathedral in a luxurious taxi and was welcomed on the stairs by his ecstatic admirers. Later I visited the church of St. Pimen (naturally, I did not receive Holy Communion and did not come to the priest for blessing) where the "metropolitan" had moved his cathedra after the Cathedral Church of Christ the Saviour was torn down. The church was visited by a pitiful handful of his adherents. I watched hasty and slipshod divine services, and listened to pretentious sermons. The last time I saw Vvedensky was in 1946, shortly before his death and the complete collapse of the renovationist schism. People whom I highly respect, including well-known clergymen, said of Vvedensky that he is an unfortunate man and deserves pity. I understood this to mean that because he was deprived of God's grace, the apostate who had ruined many people was generally unhappy despite his seeming prosperity, and he should be especially prayed for as a great sinner.

However, among the renovationist hierarchs there was a man who was respected even by the "Tikhonites" for his fulfillment of his ministry, his strict monasticism, and adherence to traditions. I am speaking of Metropolitan Vitaly Vvedensky (†1950), namesake of the renovationist leader. His cathedra was in the Church of the Resurrection in Sokolniki. Many Moscow shrines—the Iveron, Bogolyubovo, "Passion", Georgian, and "Unexpected Joy" (now in the St. Elijah Church in Obydensky Lane) icons of the Mother of God, appropriated by the renovationists, were there at that time. Metropolitan Vitaly was one of the first to repent before the patriarchal Church, to which he was reunited in the rank of archbishop.

In the house next to my own lived Vladimir Bykov, an renovationist who served in the Church of the Rzhev Icon of the Mother of God on Prechistensky Boulevard (under Communism, Gogolevsky). Wearing a kind of lace cloak instead of traditional priest's vestments, he would sit down in the middle of the church and pray aloud, say, for a woman he knew to buy good potatoes in the nearby market. He arranged spiritualistic séances in the surviving tower of the Conception Convent; once he even showed me his book with photographs of the "spirits" of great people, such as Napoleon.

I shall mention one more clergyman, but this time with a feeling of deep respect. I mean Bishop (later metropolitan) Boris Rukin (†1943) of Mozhaisk. He lived in the parish house of the clergy of the Cathedral Church of Christ the Savior. Unlike other clergymen, he appeared in the streets not in civilian clothes but in a cassock. As is known, he and Archbishop Hilarion Troitsky (†1929) of Verea were among the people closest to His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon in the last period of his life in the Donskoy Monastery. In the 1920s, he often read on Thursdays the Akathist Hymn to the Vladimir Icon of the Mother of God, in the St. Elias Church on Obydensky Lane. Refusing to accept the leadership of Metropolitan Sergius Stragorodsky (†1947), he joined Grigory's schismatics,[4] who had Moscow's Church of Forty Holy Martyrs, opposite the New Monastery of the Savior at their disposal. In all probability, this was due to the circumstance that, unlike the Renovationists, the Grigorians did not intend to modernize the Church and merely refused to accept Sergianism’s administrative aspect.

I remember that Moscow worshippers and clergymen were outraged not so much by the 1927 Declaration,[5] as by the interview Metropolitan Sergius gave in 1930, in which he said that "some churches are being closed down, however this is done not on the authorities' initiative but at the population's will and in some cases even in accordance with the faithful’s decision", and clergymen are persecuted only for political hostility.[6] It was simply impossible to understand and justify this. God alone knows what motives guided the Metropolitan... it is not up to us to judge... Probably, after such statements the primate counted on abatement of repressions. But this did not happen—persecutions were stepped up. I saw Metropolitan Sergius closely only once—in 1931, on the Feast of St. Elias, when, during the ceremony of the vesting of the bishop, I brought his saccos (the stole worn by a bishop) from the sanctuary. I was thirteen at the time, and as far as I could understand at this age, the attendants did not display the usual touching popular reverence for a hierarch.

The Theophany Cathedral in Dorogomilovo was the Metropolitan's chief cathedral. It was pulled down shortly before the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945. After that the Church of the Epiphany in Yelokhovo was made the cathedral church. Metropolitan Sergy liked to conduct services and ordinations in the Church of the Protecting Veil in Krasnoselskaya St.

The Transfiguration Cathedral in the square of the same name (destroyed in the years of Khrushchov's persecutions) was another hierarchal residence. Serving there was Vladyka Sergy Voskresensky (†1944). He was Bishop of Kolomna, then of Bronnitsy, a vicar of the Metropolitan of Moscow; he edited The Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate till the day of its decease; he subsequently became the Metropolitan of Lithuania and Vilna, Exarch to the Baltic Region. I often came to the Transfiguration Cathedral to attend his services. Nature endowed him with an impressive appearance, artistry, vitality, a strong voice (tenor) and excellent articulation but, in my opinion, his services lacked inspiration and spirituality.[7]

Orthodox

Moscow’s favorite was Metropolitan Triphon

(Turkestanov) (†1934). The Liturgy of the

Pre-sanctified Gifts, which he celebrated in the

Church of the Ascension at the Nikita Gate, was noted

for its special spirituality and beauty. Pavel Korin

painted the hierarch's portrait. Metropolitan Triphon

was buried at the Vvedenskiye Gory Cemetery. The

inscription on the base of the cross on his

grave reads: "Children, love the church of God;

the church of God is heaven on earth".

Metropolitan Tikhon (Turkestanov).

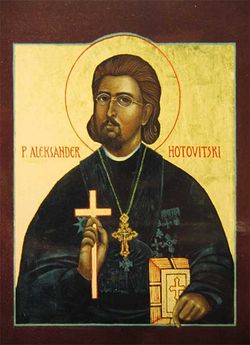

In pre-war years I often attended services conducted by well-known Moscow priests. Archpriest Alexander Khotovitsky, together with Fr. Ilia Zotikov, accompanied the future Patriarch Tikhon on his mission to America, and later concelebrated with him in the Cathedral Church of Christ the Savior. He was known for his ardent sermons and congregational, or common, confessions. For some time afterwards, he was the rector of the Church of the Deposition of the Lord's Robe on Donskaya Street. After repeated arrests he was executed by shooting.

I

received some mementos associated with the name of

Fr. Alexander Khotovitsky, after the death of M.

Avdeyeva, our family friend (she lived not far from

him in the house occupied by clergymen of the

Cathedral Church of Christ the Savior on

present-day Saimonovsky Passage). These included the

poem written by Fr. Alexander in America on the

occasion of a triple event—the Feast of St.

Elias, Fr. Ilia Zotikov's name-day, and his departure

his home country. The poem is prefaced by an

inscription: "Dedicated to my best friend Fr.

Ilia Zotikov". Well preserved is also Fr.

Alexander’s prayer book in a home-made binding

with all but indelible entries made in pencil. On one

of its sides there is a calendar with some dates

struck out crosswise, the other bears an inscription:

"Thank you, dear Marusya, for this prayer book.

It was my best, faithful companion, friend and

comforter during the harsh years of my imprisonment.

May Christ keep you safe." It remains to be

determined when and in what prison he used this

prayer book. There is also a precious photograph of

the archpriest and new martyr, excellently

conveying his ardent and infinitely kind

nature.

New Martyr Alexander Khotovitsky.

I remember Fr. Alexander Voskresensky and his splendid services and edifying sermons at the Church of St. John the Warrior in Yakimanka Street, Fr. Pavel Lepyokhin of the St. Nicholas Church in Khamovniki, Fr. Alexander Skvortsov of the former Jerusalem Metochion in the Arbat, Fr. Georgi Chinnor of the Dormition Church in Moghiltsy, Fr. Pavel Tsvetkov of the St. Elias Church in Cherkizovo, Fr. Stefan Markov of the Church of the Icon of the Mother of God "Of The Sign", Frs. Alexei Mechev and Sergy Mechev of the Church of St. Nicholas in Klenniki. In the mid-1980s, a most worthy pastor, Alexander Tolgsky, succeeded Fr. Vitaly as rector of the Church of St. Elias the Prophet in Obydensky Lane. These were illustrious personalities, people who were staunchly devoted to Orthodoxy and who left an indelible trace in the ecclesiastical life of Moscow; they raised a generation of people who have lived to see this day when the Church is no longer persecuted. Now that some eye-witnesses of the past are still alive, it would be appropriate to compile for the church press essays devoted to Moscow clergymen (and not only Moscow clergymen, of course) of the past. Their names should be constantly remembered in prayer in the churches where they once served, especially during the years of persecution. The fine words of a Soviet era poet: "nobody has been forgotten, nothing has been forgotten", have lost their value in our life full of vanity, and only the Church preserves the prayerful memory of people who have passed away, and who are still alive.

Although there were rather few churches left in Moscow, there was often a shortage of priests for celebration of early Liturgies on Sundays and feast days. Retired priests were often invited in such cases. Thus, Fr. Phillip, a very aged priest from the then closed St. John Convent, was usually invited to serve in the Church of St. Elijah in Obydensky Lane. There were no schools for training clergymen. True, in the 1930s, the personnel of the miraculously surviving churches was replenished as a result of the merger of parishes. It goes without saying that, as a rule, clergymen were far from young, and they enjoyed the love and profound respect of their parishioners.

In those distant years there was a custom to invite well-known archdeacons on local or patronal church feasts. One of the greatest favorites of Orthodox Moscow was Fr. Mikhail Kholmogorov. His peculiar appearance was immortalized by Pavel Korin in his famous canvas, "Departing Rus". Unlike Fr. Vladimir Prokimnov, another famous Moscow clergyman, Mikhail Kholmogorov continued his church service to the end, and during the last years of his life served in the former Jerusalem Metochion in the Arbat. His voice lost its former strength but preserved its noble timbre even in old age. The archdeacons had their favorite repertoire: Lyubimov's "Blessed is the man", M. Strokin's "Lord, now lettest Thou thy servant depart in peace…", P. Chesnokov's "Save us, O Lord", A. Arkhangelsky's "Creed", Communion "concertos" by various composers. I happened to attend a church service conducted by Maksim Mikhailov; true, it was not long before he became a professional singer.

Needless to say, in those years clergymen were very highly qualified; they knew liturgical services by heart and could do well without the service book. Sermons were of a purely religious nature, without any excursions into science and politics. There was no abuse of apocryphal traditions. It never occurred to anyone at that time to touch upon issues which preachers sometimes discuss today: whether or not the Mother of God experienced pain during the birth of the Savior, what did She look like, who to pray to before shopping, etc. And, of course, there were no lists on church walls recommending what saints to pray to for specific occasions, like Martyr. Antipas for a tooth-ache, St. Artemy for a rupture, and so on.

Church awards were generously dispensed. Practically all Moscow priests were mitred, which is quite understandable—they were elderly people and had a long record of priestly service.

Sisterhoods became widespread. Young girls, adult and elderly women, wearing modest dark clothes and white headscarves, maintained order during divine services, lighted candles, adjusted lampadas, led children and infirm worshippers to the Communion chalic, the Cross and icons, and went about the church with a plate, collecting parishioners' modest donations.

Sisterhoods' functions were limited to the church; charity and similar activities were prohibited by the civil legislation then in force. Sisters were not nuns; many of them were married and had children.

As a rule, the psalm readers who served in churches were excellent. They read distinctly, observing logical pauses and stresses; their reading was devoid of indifferent mumbling or deliberate, purely secular, expressiveness. And, of course, they knew Church Slavonic and service procedure to perfection. For instance, one fine point, which is marked in all Horologions but invariably ignored today, was strictly observed at that time. Church people were reluctant to use liturgical books with secular type (as opposed to Church Slavonic lettering). Very often the Six Psalms and pre-Communion prayers were read by parishioners, who did it with great reverence and diligence.

In divine services, particularly at Vespers, Compline, and Matins, some reductions were allowed at the expense of stichera and Old Testament readings. Lights were not switched off during the singing of "Open unto us the door of repentance".[8] Akathists and molebens with the blessing of the waters were not conducted in churches as often as they are now, and there were no mass or congregational Unction services.

The time of divine services was fixed to suit working people and not only pensioners: on weekdays Divine Liturgy was celebrated at 6:30 a.m., and evening service started at 6:30 p.m.

What was church singing like in those distant years? The famous synodal choir, conducted by Danilin, which sang in the Kremlin Cathedral of the Dormition, has long since become a thing of the past, but Danilin's name has not been forgotten. Yukhov's choir changed hands, becoming a radio company, and the choir conducted by Chesnokov is no more. In the late 1920s-early 1930s, the best church music ensemble was the choir conducted by Nesterov and then Antonov. It sang in the Dorogomilovo Cathedral. Part of the choir was invited to sing in other places, for instance to sing the Akathist to the Icon of the Mother of God "Unexpected Joy" in the Church of the Laudation of the Mother of God (the louder, the better), often without going into the meaning of the words. Besides, this deprives us, probably for ever, of the possibility to enjoy the wonderful, profoundly prayerful music: A. Kastalsky's and A. Grechaninov's "I Believe..." (The Creed), and "Our Father" by Kedrov, K. Shvedov and P. Chesnokov. In general, without favoring a vulgar, concert style of church singing, it is hardly worth neglecting the aesthetic side of divine services, including singing, reducing everything to custom and completely rejecting the heritage of church music composed by our native composers. God granted them talent, and they devoted it to the service of God. We are sure to become spiritually poorer without D. Bortnyansky's "Cherubic Hymn", A. Lvov's "Mystical Supper", P. Zinovyev's "God Is With Us", P. Turchaninov's "Let All Mortal Flesh Keep Silence" and much else. Besides, as opposed to anti-human and depraved rock music, the melodious, profoundly national, exalted and inspired Orthodox music purifies spiritual nature of people, especially young people—and not only of those who regularly attend church, but also of those who come there out of curiosity.

Inasmuch as religiosity was cruelly persecuted, and at school and in "politically conscious" families children were educated as atheists, very few young people visited the church. In my childhood and youth, and even as recently as some six years ago, parish Sunday schools and children's choirs singing in churches were well nigh impossible. But can one fail to rejoice now at the sight of children dressed in their Sunday best, calmly standing on the solea, assiduously making signs of the cross, kneeling, collecting candle stubs from candle stands, and joining adult parishioners singing? People of my generation cannot but be happy for the young men and women who now stand in churches, following the divine services with awe and attention, using books published by the Moscow Patriarchate.

Most of the pre-war parishioners managed to acquire elementary religious knowledge before 1917, knew liturgical routine well and were free from the prejudices that have become so widespread now; such as passing candles only over the right shoulder, stretching forth their palms at the pronouncement of “Peace be to you all”, lighting candles before specific saints’ icons for specific categories of requests (according lists earlier mentioned), and did not go to cemeteries to pray for the dead on Bright Monday, since the day the Church has designated for this is the Tuesday after Bright Week (Radonitsa). The religious intelligentsia did not combine Christian convictions with anti-Christian mysticism — astrology and other doctrines.

People stood still in the church, and it never occurred to anyone to walk about, elbowing parishioners. They usually went to one and the same church, especially on feast days. They kept to their own parish, knew each other well, and each had his or her own usual place for praying. An atmosphere of kindness and goodwill reigned in church: nobody was rebuked, nobody hissed spitefully at bare-headed women. Service personnel was not unceremonious with shrines, there was nothing deliberately masterful in their deportment, nor did they bark out orders, spoiling parishioners' moods. Prior to Khrushchev's "reform", the main figure in church was the priest, and not the churchwarden or charwomen. Incidentally, despite the oppression and control on the part of the state in those years, priests managed, with the hem their black cassocks tucked up under their coats and accompanied by psalm-readers, to go about (though on the sly) to the homes of the parishioners they knew on Christmas, Theophany, and Easter to serve molebens there.

Regrettably, I must say that at that time people were not overly particular about fasting; they rarely took Holy Communion—for the most part on Holy Thursday and Palm Sunday, and on their name-days.

Looking

back at the life of Moscow parishes in the not so

distant past, one can see its strong and weak points.

But though we rejoice in the reopening of churches,

their being attended by numerous worshippers, the

great number of needs and offices conducted there,

the religious radio and TV programs and various

publications on religious themes, it would be too

early to celebrate victory: in many respects the

process is going ahead in breadth rather, than in

depth. Looking at the experience of former parish

life in Moscow—the center of Russian

Orthodoxy—can be of extremely great benefit: it

will help to duly appraise and revive religious life

today.

"Requiem" by Pavel Korin.

From The Journal of

the Moscow Patriarchate, 1993, No. 4. Edited by

OrthoChristian.com.