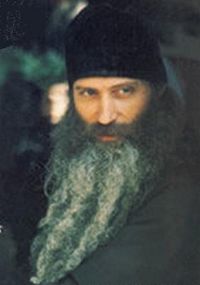

Hieromonk Seraphim Rose.

Hieromonk Seraphim Rose.

Early years.

Born Eugene Rose to an ordinary lower middle-class family in San Diego, California, the future Father Seraphim was distinguished even from early childhood by his seriousness and strong intellect. His natural self-restraint and willingness to submit to his parents made him their pride and joy. He inherited the practicality and ability to see through falsehood from his hard-working, no-nonsense mother and his meek but wise father, both of whom were the American salt of the earth, forged under the pressures of the Great Depression.

His teachers at school even felt a little intimidated by his seriousness. They felt as if they had to be on their toes in his presence, so not to waste his precious learning time. He excelled in all subjects, especially mathematics and foreign languages. Despite his obvious genius, Eugene’s modesty never allowed him to feel better than his peers, and the satisfaction of scholastic mastery never overpowered his awareness of being somewhat isolated from the rest. This same unpretentious studious drive would later manifest itself in a desperate search for truth that would take him down a dangerous path, but finally deliver him home to a greater truth found only in Christ.

University.

Eugene’s family was Protestant and church-going, and this provided the religious background of his formative years. But by the time he entered the conservative Pomona College in Southern California, he had rejected the Christianity of his childhood as too complacent and materialistic. His diamond sharp intellect had pushed it all aside, as can be seen from a paper he wrote in his freshman year entitled, “God and Man: Their Relationship”. ‘Universe’ is my term for ‘God’”, reasoned the critical Eugene. “It is an improvement over the latter term, I believe, for it far more readily conveys the impersonal, unified, concept I wish to present…. All science points to the existence of the Universe, the totality of all things. Nothing in science points to the existence of a God removed from the Universe. For the present time, since I have not yet developed my own theory of knowledge, I assume for convenience’s sake that I can gain knowledge (as certain as can be obtained) through science. Therefore, I believe in the findings of science that point to the existence of the Universe; I reject the concept of an independent God for insufficient evidence.” Nevertheless, he had not rejected the concept of human happiness. “Man should live for his happiness, accepting the times when he is not happy merely as passages to higher times; his love of the Universe will tide him over to better times.”

The rational approach to belief in God combined with a natural, irrevocable need for some form of personal contentment could not but impel Eugene towards a search for happiness without God. As his biographer, Hieromonk Damascene writes, “Young idealists who are rebelling against the Christianity of their childhood, who can accept nothing above the rational and yet are seeking something else to satisfy their spiritual needs, are apt to hear the call of a number of different siren voices.” So it was with the young, intellectually vigorous Eugene. His longing for something greater than himself led him like a moth to the flame of such German philosophers as Friedrich Nietzsche, whose heated embrace of a “Superman” had drawn him into the delirium of nihilism, and eventually closed his aging lips with the muteness of insanity.

Eugene’s end, as we know, was very different from that of Nietzsche. But he would have to pass through the same dark furnace in order to reach a permanent, eternal light, a cool refreshing place of eternal happiness. As Hieromonk Damescene writes, “Eugene had begun his philosophic search by repudiating the very thing he was seeking. At the deepest level, he was being driven to find God, but he would have to go full circle before unexpectedly returning upon that from which he was running.”

From a mathematician Eugene became a philosopher. He remained an amiable young man with a good sense of humor and a close circle of friends, but there was an enigmatic side to him that no one around him understood. He would often take solitary nocturnal walks, brooding over something that he revealed to no one. This introverted brooding would later spill over the surface in rare moments of lowered self-restraint, when he would literally rage against a God he didn’t believe in, challenging that very God to make Himself known.

Oriental philosophy.

The material light of Western philosophy finally burned down and fizzled in Eugene’s mind. It had left him wanting, and so he set off in the direction of Oriental philosophy. The early 1950’s saw the rise in fame of a former Anglican priest who had embraced Zen Buddhism, Alan Watts. Watts had something alluring to say to a spiritually dispossessed generation, and he became very popular. “Watts surprised his young listeners by telling them that the whole structure of the Western thought they had been studying was completely wrong-headed…. The secret of life is to stop thinking about it, and just experience it.” Watt’s Western assimilation of ancient Oriental thought would prove to be a turning point in American popular culture. Although it was taken from a tradition of strict self-discipline, its transplant onto American soil would produce fruits of plain hedonism and a seeking of what “feels good”—experience for the sake of experience. Watts himself would become disillusioned and bitter toward the end of his life, left unsatisfied and empty.

Eugene’s exploration of Zen Buddhism did not conflict with his atheism. But it would never really answer his deeper questions and needs. His close friend Alison would later relate that Eugene had thrown out his aspirin and alarm clock as thing unneeded by a practitioner of Zen. As a result of his “renunciation”, she would have to supply him with both, because he couldn’t function without pain relievers, and if she didn’t knock on his door he would be late for class. She said about that period, “Zen helped Eugene in a negative way. He went into it with the idea of finding knowledge of himself, and what he found was that he was a sinner. In other words, it awakened him to the fact that he needed something, but provided no real answers.”

This same Alison was a believing Christian in the Anglican faith, and was ironically the only person who, as Father Seraphim would later note, actually understood him. “Although Eugene was the most openly atheistic of all her peers at Pomona,” Hieromonk Damacene writes, “Alison recognized him as being also the most spiritual. ‘Even when he was an atheist,’ she says, ‘he gave it his all’.”

After Eugene had moved to San Francisco to enroll in Watt’s Academy of Asian Studies, he began to reach the culmination point of his own spiritual despair. Amidst a plainly hedonistic life of tasting all that city had to offer, he still pondered the writings of the nihilist Nietzsche. This once brought him to what he would later know to be the brink of hell, a partial state of demonic possession. One day, after spending hours reading Thus Spake Zarathustra in the original German, he took an evening walk against the blood-red sky of a San Francisco sunset. “As he came to a certain spot on the street, he heard Nietzsche’s poetry resonating inside of him. He felt that ‘Zarathustra’ had actually become alive and was speaking to him, breathing words into him. He felt the power of those words as one feels the charge of electricity, and he became terrified.”

“Deep calleth unto deep.”

There is an enigmatic passage in the Psalms that says, “deep calleth unto deep”. In the Russian Church Slavonic, it sounds more like, “the abyss calls to the abyss”. Some patristic writings explain this passage: The abyss of depravity and sin often exist right next to a depth of wisdom and faith. When a person reaches the very pit of destruction, he may be not far from a complete turnaround to the depth of wisdom. San Francisco, known as a very elite and refined type of “sin city”, would turn out to be the place where the future Orthodox monk would turn away from the siren song of a burned out Alan Watts to find a holy man and wonder-worker of the Orthodox Church—St. John Maximovitch of the Russian diaspora.

Realizing that Watt’s dilettantism satisfied neither his soul’s desire nor his scholarly scruples, he began to study the French philosopher, René Guénon (1886–1951). Father Seraphim would later write in a letter, “It was René Guénon who taught me to seek and love the Truth above all else.” This philosopher inspired Eugene to get to the core of Chinese philosophy by studying it from its traditional practitioners, in the ancient Chinese language. It started him on his honest search for authentic religion, which finally took him to a Russian Orthodox Cathedral.

Full circle.

San Francisco was the final home of a large number of Russian refugees from the Bolshevik revolution. Most of them had been brought from China by their saintly archbishop, John Maximovitch. After years of excruciating search, now open to the concept of authentic religion, Eugene was persuaded by scholarly colleague to at least explore a Church where original Christianity can be found—the Orthodox Church. When Eugene entered the Old Russian Cathedral of the Mother of God “Joy of All Who Sorrow,” he knew that he had found his home. It proved not to be a passing moment, for Eugene would soon be received into the Orthodox Church, and catechized by a man who that same Church would later glorify as a saint. Seeking more than simple contentment and religious life in the world, Eugene was to find the final refuge for his deep, truth-thirsting soul in the wilderness of Northern California, as a monk in the ancient Orthodox tradition.

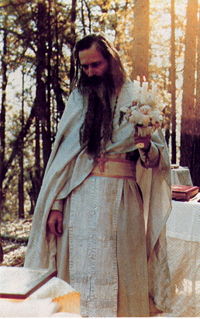

Father Seraphim lecturing in Platina,

Father Seraphim lecturing in Platina,

Father Seraphim’s life in the wilderness monastery dedicated to St. Herman of Alaska, which he co-founded in Platina, California, was intensely fruitful but relatively brief. He did not live to venerable old age, but died at the age of forty-nine. The illness that had almost killed him in San Francisco before his monasticism led him to fervent prayer to the Mother of God. Having at last found his soul’s desire, he begged for time to redeem himself. This prayer was answered, but now the time had come when this flame now burning with divine light would no longer be seen in this world, only to burn brighter in the next.

His repose.

Father Seraphim suffered intensely from a rare illness of the colon an entire week before his death. He was hospitalized during that time, and the doctors did all they could to save his life, but the disease had progressed too far before he felt the need for medical help, having always been accustomed to bearing fatigue and physical discomfort as a true ascetic. His spiritual children and his co-struggler, Father Herman, the abbot of the St. Herman Brotherhood at the time, kept constant vigil at his hospital room, and one of the sisters of St. Xenia Skete, a monastic community for women Father Seraphim had started for his spiritual daughters, was the last person to see him in this world.

Those close to him would feel this great loss for perhaps the rest of their lives, but Father Seraphim seemed to reach out to them even on his deathbed, and beyond. One of these was his close friend, Mrs. Helen Kontzevitch, who was living two hundred miles away in Berkeley, California. On the morning of Father Seraphim's death she had a dream. “I was in the company of a priest unknown to me…. Together we entered a large, palatial hall. At the end of this hall a man was standing on a raised platform and singing. It was difficult to see him well because of the distance. In a most beautiful voice he was singing the magnification hymn [to the Mother of God], ‘My soul doth magnify the Lord…’ The singer was a tenor with a voice like Father Seraphim’s, whose singing I had heard years ago in the San Francisco Cathedral. That had been in the early 1960’s when, standing in the kliros, he alone had sung the Matins service from beginning to end. Never in my life had I heard more prayerful singing. My soul had been uplifted to the heights…. Now in my dream, I heard that same incomparable singing. It was the same voice, but it sounded like that of an angel, a dweller of Paradise. This was heavenly, unearthly singing. Waking up, I understood that there was no hope for Father Seraphim’s recovery.” It is interesting to note that Father Seraphim died during the after-feast of the Dormition of the Mother of God.

Father Seraphim’s old friend Alison, now a widow living in Kansas, was also given a mysterious indication of Father Seraphim’s impending death. She did not previously know about his illness. In a dream she saw him tied to a bed (as in fact he was due to the unbearable pain), and she saw terrible physical agony in his eyes, such that it was painful even for her, a nurse by profession, to behold. She saw that he was unable to speak. She immediately wrote to the monastery to find out if anything was wrong, but received an answer only after he had passed away.

Father Seraphim in blessed repose. His face was so peaceful and beautiful that the traditional face cloth was removed.

Father Seraphim in blessed repose. His face was so peaceful and beautiful that the traditional face cloth was removed.

The church was filled to overflowing, and all felt an incredible outpouring of grace. It was more like a solemn and joyous feast than a funeral service. The sorrow of those there turned to joy, when at the lowering of the coffin into the grave, all spontaneously began to sing the victorious Paschal hymn, “Christ is Risen from the dead!”

Spiritual help from the heavenly realms.

Even after his repose, Father Seraphim served to strengthen converts to Orthodoxy in his native land. The books he had written during his ascetical life in the Platina monastery have had a far-reaching effect, and brought many to the faith. He has even appeared to people at crucial times in their lives, such as in one incident experienced by a former Catholic. This man was preparing to participate in “Operation Rescue”, a protest before an abortion clinic that would take place on Holy Saturday, the day before Easter. He had seen Father Seraphim’s picture on a copy of the periodical Orthodox Word, which is published by the St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood in Platina. Very anxious about the Operation the night before, he fell asleep restlessly, “only to be awakened shortly thereafter with Father Seraphim Rose’s face gleaming at me,” he would later write to the monks at the St. Herman Monastery. “I knew that I was to pray to him that he would pray for my protection in ‘Operation Rescue’…. When I awoke in the morning, Father Seraphim was still with me.” When the man took his place blocking the doorway to the abortion clinic along with thirty-two other Christians, he could see Father Seraphim looking at him and protecting all of the other Rescuers.

Although the group was arrested, they were treated very kindly by the police, much unlike previous Operations, and charged with no more than a “Class A” misdemeanor. The police intentionally put their case on the docket of the only pro-life judge in the precinct. This man, Dr. Stephens, was received three months later into the Orthodox Church along with his family, taking the new name Seraphim out of gratitude to Father Seraphim Rose. His is now a priest in the Orthodox Church, serving in Virginia Beach, Virginia.

Another future Orthodox priest, Father John Mack, had a miraculous conversion through Father Seraphim. At the time he was a minister in the Reformed Episcopal Church, studying at the theological school in the University of California, Berkeley, and was in a serious spiritual crisis: “I had been a Christian all of my life, yet I did not know God,” he relates. I knew a lot about Him, but I had no relationship with Him and did not know where to start. To make matters worse, I was closely involved with other religious leaders and found that, like me, they too were empty. Everything religious seemed fake to me, without authenticity and without meaning…. I was at the end of my rope; I had even come to the point where I did not know whether I could believe in God. ‘Is it real?’ ‘Is this just a game that people play in order to manipulate and control others?’ ‘Is there such a thing as a holy man?’ I knew that the answer to my question could only be found in the existence of a holy man or woman. Nothing else could answer the longing of my heart.”

He was sitting in the University library doing research, when this crisis came to a head. He could not help but cry out to God, “Is it real? Does a holy man exist?” He wept, years of struggle and disappointment washing over him in waves. After some time, he came to himself and absently looked over a stack of books, but found nothing to solace him. He then returned to his desk, and was taken aback by a catalogue advertising books that he suddenly found amidst his books and papers. He saw on the front page a picture of a man who he learned from that catalogue was Father Seraphim Rose, and his questions were immediately answered. He knew right away that he was looking at the image of a holy man. As he stood pondering the effect that this picture had on him and what was this Orthodox faith that he found advertised in the catalogue, he felt a man touch him on the shoulder. “Would you like to be Orthodox?” the unknown man asked him.” “I don’t even know what Orthodox is,” he responded. The man scribbled a name and phone number on a piece of paper and gave it to him, saying, “Here, call this priest. He can answer your questions.” He looked at the paper and saw the name, Father Antony, but when he looked up again, the man was gone. He asked others at the library, but no one had seen him come or leave.

The future Father John called the surprised Father Antony when he arrived home. As it turned out, Father Antony had only just moved to that locale three days before, and only a few people knew his number; not even the Archdiocese had it yet. Father Antony was also a convert from Protestantism, and was able to give needed guidance to this confused Episcopalian minister who had just been introduced to the Orthodox faith by the picture of a man he recognized as holy—Father Seraphim Rose.

Memory eternal.

Father Seraphim at his last Paschal service in Platina.

Father Seraphim at his last Paschal service in Platina.

Holy Father Seraphim pray to God for us!

Information for this article was taken from the biography by Hieromonk Damascene of the St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood entitled, Father Seraphim Rose. His Life and Works (St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood, Platina: 2003). For more information on this biography, please see the website, stherman.com.