SOURCE: Icons of Insight · St. Alban in the Valley

by Father Michael Gillis

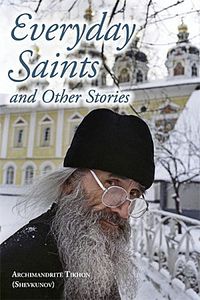

I’m reading Everyday Saints and Other Stories by Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov). I’m only 46 pages into this 500 page collection of stories about holy “everyday” people in Russia, but based on what I have read so far, I think I can fully recommend it. The translation is excellent, revealing Archimandrite Tikhon’s skill as a story teller.

The first story (or set of stories) in the book is about Elder John, Archimandrite Tikhon’s spiritual father for twenty-five years. These stories about Elder John are amazing, encouraging, and both fearsome and hopeful. Elder John at one point relates a story from his youth. It is a story of an Archbishop Seraphim, whom the then twelve-year-old John revered. On Forgiveness Sunday, the Archbishop drove both the Abbot and a deacon from the monastery, then went into the monastery church and conducted the service of forgiveness, prostrating before all present and begging their forgiveness.

“My youthful conscience was totally shocked,” Elder John relates, “by what I had just seen, because of the utter contrast: on the one hand, and act of driving out from the monastery, in other words, the absence of any forgiveness, and yet on the other hand, his meek plea for forgiveness for himself and others from all and to all. At the time I only understood one thing: that sometimes punishment can be the beginning of forgiveness, and that without punishment forgiveness may be impossible.”

Without punishment, forgiveness may be impossible. What a strange idea for my western mind. In our western way of thinking, punishment and forgiveness are opposites. We usually think of forgiveness as replacing punishment–that is, those who are not forgiven are punished, and those who are forgiven are not punished. But what Elder John speaks of is a punishment that makes forgiveness possible.

Certainly he does not understand punishment juridically. He does not understand punishment as a necessary paying off of one’s debt to society or to God. He does not understand punishment as a kind of balancing of the scales of justice that have been thrown off balance by one’s crime, by one’s sin, and require punishment to rebalance them. If this is not what punishment is, then what is it? How do we translate what a Russian Orthodox elder means by punishment into language that a contemporary western English speaker can understand?

One way to begin to understand what an Orthodox elder might mean by “punishment leading to forgiveness” might be to look at some of the work that has been done by truth and reconciliation groups trying to bring peace to war-torn parts of the world. What they have found is that in order for reconciliation to take place between alienated factions, truth must be told. That is, those who have perpetrated heinous crimes must admit what they have done. However, this is not easily done, for those who commit heinous crimes often do not view themselves as criminals. They may view themselves as patriots or as innocent victims themselves merely following orders, or as initiators of a new and better order of things; but they certainly do not see themselves a criminals. Nevertheless, if reconciliation is going to take place, truth must be told.

Similarly in a spiritual sense, confession of sin must precede forgiveness. This is, of course, from a human perspective–God has already forgiven everyone. We are the ones who need to experience forgiveness. God always forgives everything. But in order to experience God’s forgiveness, we must accept that we have sinned. Just about everyone is willing to admit that they have sinned in some way or another, or to own up to a vague sinfulness. However, the real difficult part is to admit, to really own, specific actions, words, thoughts and attitudes as sinful. Often, and this has been the experience of the Church, only a certain amount of suffering will bring us to our senses. It seems that in our pain we are able to see a little bit of the pain we may have caused others. It seems that in our pain we cry out to God for help, to a God that may seem to us to be silent, even absent. But this prayer itself draws our attention to what is in our heart, to the truth that we have striven so mightily to deny.

This suffering we call punishment, again not because we are paying for a crime, but because we know at some level that our suffering (and the suffering of others) is connected to our sin. In fact, admitting this fact, that our suffering and the suffering of others is in some way connected with our own sin, often is a first step in finding healing, in finding reconciliation with God and neighbor. The parable of the Prodigal Son is an example of this. It is his suffering, which is not unconnected to his sinful actions, that brings him to his senses, that brings him to admit to himself and to his Father, “I have sinned against heaven and before you, and am no longer worthy to be called your son….” The Father holds no grudge. He does not delight to see his son suffer. The Father is ready to forgive, indeed has already forgiven; but for the son to experience this forgiveness he himself must “come to his senses” and admit to himself that he has sinned.”