On April 10, 2012, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Ukraine stated that the military court in Libya has postponed its review of an appeal on behalf of 19 Ukrainians and one Russian citizen given prison sentences for allegedly supporting the government of Muammar Gadhafi. On June 27, 2012, Orthodoxy in the Ukraine, published an interview with priest Zacharias Kerstyuk about his ministry to these simple migrant workers caught in the merciless storm of “Arab Spring”. This article was recently translated for OrthoChristian.com.

* * *

I was naked, and ye clothed me: I was

sick,

and ye visited me: I was in prison...

An

Orthodox priest—Fr. Zacharias

Kerstyuk of the Department for External Church

Relations of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, went on a

mission to Libya, where he was able to meet with

prisoners. Recently, the Libyan court sentenced 19

Ukrainians to 10 years in prison, and the team

leader—a Russian citizen—to life

imprisonment.

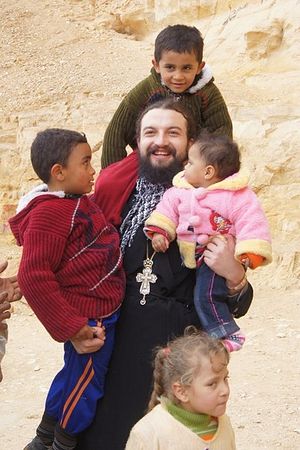

Archpriest Zacharias Kerstyuk.

What were the Ukranians actually doing in Libya and why of the 5 million people in Libya are there 2 million immigrant workers? Is it dangerous to preach Christianity in “liberated” Libya? And, why did an Orthodox priest go on a mission to the Islamic world? Archpriest Zacharias Kerstyuk tells us all about this as well as other topics regarding "Orthodoxy in the Ukraine".

"The average age of prisoners is 55 years, and these are people with far from excellent physical health"

—Recently, a military court in Tripoli accused the Ukrainian prisoners of fighting on the side of Gaddafi during the Civil war, and gave them 10-year prison sentences. From photographs, the prisoners look at us, the faces of engineers already elderly ...

—Are you able to determine their professions from their photographs?

—I mean those who are depicted in the photos do not look like people who run around with guns mercilessly killing everything that moves.

On the one hand, it is hardly possible to determine by their photographs: is this person a football player or engineer. On the other hand, it is possible.

The average age of the prisoners is 55 years old, and these are people with less than perfect physical health.

In general, it should be said that the social situation of our country [the Ukraine] is such that people have to leave the country in search of well-paid work. According to statistics, currently 8 million of our countrymen have left in search of a better life abroad. This "better life" is not necessarily as a permanent resident or with a high standard of living. These might just be some temporary jobs and life in poor conditions, which leaves a certain effect in the soul and mind of every man. People go to Africa, the Far East and Western Europe.

Some of these people who went abroad for such reasons ended up in Libya, where they found themselves hostages to the so-called "Arab Spring." One of the prisoners went to Libya to earn enough for his grandson to undergo an operation, another to collect money to make repairs in his apartment, and a third went to make money and pay off debts. That is, we need to understand and take into account the fact that people did not come to help put someone into power or kill someone. They came to earn money for the most essential needs. And they did not go there for the "good life."

This is a painful issue for our nation. Why? Because those people who travel abroad usually work there under difficult conditions.

If this is Spain or Portugal, people would work somewhere on farms, live 20-30 people to a room, manage to earn 800 euros a month of which 600 is to sent to their homeland, and the remaining 150-200 euros spent for living expenses.

If this is Italy, our immigrants work for Italian families—caring for the sick, the elderly, for children, or cleaning homes. The treatment by their employers is, in general, not very humane: A day off—Sunday—and all the rest of the time they live with these families. In fact, they are hardly given time to communicate with their own family or just to go on a walk.

If it is Africa, the people there are unable to communicate with their own family—there is rarely an internet connection or telephone available, and they rarely hear a native voice.

All this leaves an imprint, and somewhere in their hearts—let’s be honest—they hate their homeland, God, and family.

Children grow up without parents, parents without their

children, or missing their husband or wife. Most create a

‘temporary’ family abroad, justifying it by

the fact that they somehow need to survive. At home,

it’s the same situation.

It is not the immigration typical of the 19th and early

20th centuries, when the “best minds”

emigrated abroad. Whole families, columns, with carts of

posessions, cows and more. They were met with joy, given

housing, benefits, and they assimilated and found work in

their new homeland.

This immigration is simply a "physical resource." As soon as the physical resource is exhausted, our people will not be needed and will have to return home. It will be a massive return of people with mutilated souls and destinies. And it will be a painful issue for our state.

Therefore, the Church tries to somehow take care of our people abroad, to organize different missions, even in the most difficult and dangerous places on earth. Moreover, in addressing such problems, the Church, more than ever, must stand shoulder to shoulder with the State.

"With Muammar Gadhafi, of the 5 million total

population 3 million were migrant workers—who

created this situation”

—You mentioned that our people abroad have hate in their hearts for their home and God. But in fact there are cases when people who live and work abroad are brought closer to the Church, and then return home and bring their children closer to the faith.

|

However, when I meet them for the first time, they ask that I don’t even serve—better to tell them about their homeland. After listening to them, I tell them, let us pray together and talk about God.

Those who cling to this outlet— faith, of course—find their place in the church, and all that happens to them is open to different interpretations. They start to feel differently and lead a different type of life. Those who continually blame the county they find themselves in, their broken families, and the State, often go to the extreme in their thoughts—that it is all their fault, and that God has sent them special difficulties in their life. Hence the hatred of all things.

Here one’s ego comes to play, ones sense of self, because everyone thinks that it is heavier and worse for them than it is for everyone else, that no one understands them. Only "me", "me", "me" ... Unfortunately, the problem of ego is shared by almost everyone these days.

Something similar was experienced by the Epicureans and Greeks in the time of Christ. They experienced the same apathy, frustration and complete absurdity. These are usually symptoms of dying nations.

And what are Ukrainians typically engaged in—those who leave to work in Libya?

Our people who work there are mostly doctors. About 8

thousand Ukrainians were employed in the medical field

before the revolution.

In general, Muammar Gadhafi spoiled his people so much

that Libyans almost never worked. Free medical care, free

education, two men from the family were entitled to free

tuition at any state institution in the world, electricity

for the population was paid for, a young family received

from the state free housing and a car, all of the oil and

gas proceeds were distributed so each Libyan received a

$400 per month allowance, the unemployment payment was

$730, and the minimum salary was $1,000.

In fact, it did not make sense for citizens to work. In addition, they partly considered themselves a “chosen people.” Therefore in Libya under Muammar Gadhafi, out of the 5 million people it was the 3 million migrant workers who did all the labor.

The immigrant labor was mostly Egyptian, Turkish, and even Europeans. Libyans mostly held some public office or engaged in a lucrative business— that is, one that brought in a high income.

"In fact, the first time the leader of the group that captured the prisoners met us, he was carrying flowers."

—Lets return to your meeting with the Ukrainian prisoners. Why you were allowed to meet them?

God

made it happen! The meeting with our prisoners

was an incident unprecedented in world diplomacy. For

the first time the leader of the group that held the

prisoners, met us—basically, his

opponents—with flowers in his hands.

Moreover, all of the prisoners were put in a room where the floors were covered with carpets, had juice and water, and each was given flowers and gifts. For a long time I tried to understand the meaning of these gestures...

Maybe they wanted to say that "The prisoners are held in excellent conditions and, in fact, are loved?"

I do not think so. Usually, they do not care, they do not even attempt to show that they are humane and just say that people are guilty and therefore they are imprisoned.

By the way, the leader of this group was an Islamist, but he came out to meet us and congratulated us with Easter (the meeting was held during the Easter holidays): "I congratulate you on the great Christian holiday of Easter!" I even gave him an Easter egg (I decorated the eggs sitting there in Libya at midnight) and greeted him with the words "Christ is risen!" To which he kindly responded.

Then they all left the room, leaving only a couple of people at the entrance with automatic weapons. Because we stayed in the room itself, the prisoners had the opportunity to write letters to relatives in Ukraine and Belarus, which I later took and distributed to their families. I also carried a phone—I had not been searched, and the boys had the opportunity to call their loved ones. Some of the prisoners talked with their families for the first time since their travel abroad. The meeting lasted 2 hours and 40 minutes, so all of them had a chance to talk.

At first glance, the damage to them did not seem much. Of

course, the people looked very tired and exhausted. Nine

months in captivity will be felt, however well they were

treated in prison, especially so far away from their

homeland.

Currently the Ukrainian Embassy in Libya is making every

effort to influence the situation and change the

prisoners’ conditions.

And how were the meetings with the relatives of the prisoners?

The first meeting was very difficult in the spiritual sense; it lasted around 7 hours. I wanted to pick out words of support for the relatives, to comfort them. There were tears and joy. Then we agreed to meet regularly. The second time we met, they had confessed and received communion, I celebrated the liturgy and prayer service. This meeting was better spiritually and emotionally. With God it is easier to experience grief.

"If they see that an Orthodox priest ministers to the Libyans, all can be severely punished"

—In Libya, more than 90% of the population is Muslim. Are there Christians only among our people, or are there also Christians among the local population?

|

By the way, Muammar Gadhafi did not give citizenship to anyone except Libyans, and thus there were never clashes between Muslims and Christians.

But Muslims must be understood. They have a different temperament than we have, they speak loudly and emotionally, using vivid gestures, and visitors often feel like they are showing disrespect because of this. But in reality, it is simply a style of communication. It took me a long time to get used to this, but I funally understood that there is nothing in this.

If we come to Egypt and go to the market, traders lured us: "Come in, come in." We do not go in and they turn around, waving their hand at us in seeming malice, but in fact they wish us no harm. This is just their custom. And we, based on our own customs and mentality, thought they wanted to cheat us.

We are deceived most often because we want to be deceived. For Arabs, it is very important how you are feeling. They always carefully look at your eyes. If they see confidence, they will be courteous, and if they see the opposite—they might try to take advantage of you. You know, like children. If the child has a tantrum, and you are acting calm and ignore them, it disappears. But if you start to respond, it will incite them even further. The Arabs are in some ways child-like, and perceive things as children do.

For them, a very important point is resentment or betrayal. If they are hurt or betrayed, restoring the relationship is almost impossible. For us, betrayal has only recently ceased to be something awful.

If you negotiate something in the Arab world, and then leave and come back six months later, the agreement shall remain in force. As for us—as soon as we leave the office we hear “No one promised, I do not remember that being said..." In the Arab world there is nothing like that.

Many will say, "If the Arab world is that way, then why is there so much bloodshed there now?" I talked a lot about this. You have to remember that everything shown about the the so-called "Arab Spring" is not Libyan TV, you have to divide it by about 90%.

Gadhafi did not launch his airforce; as a result, allegedly, hundreds of civilians were killed. Rather he tried to do something to calm the people. Muammar Gadhafi was not a "tyrant and dictator,” but a guarantor of a quiet life in Libya.

But we swallow everything we are fed by the media about the "Arab Spring," along with the masses.

—How do Muslims of the current time view Christians? The journalists who cover the "Arab Spring," write that in insurgent activities in Syria are affected by religious background, and the facts point to destruction of temples and torture of Christians. Is this not similar in Libya?

The government of Libya currently consists of people who have lived in the US for 30 years, and for whom religious issues are practically of no interest. On the other hand, there are factions trying to come to power who represent a more radical Islamic movement—the Salafis. If they take over, then, of course, they will try to introduce Sharia law. In this case, Christianity will experience hard times.

But in fact there is virtually no Christianity in the region. If there is, it is just the pastoral care of foreigners.

By local laws, if they see that an Orthodox priest ministers to Libyans, severe punishment can result, including the death penalty. In such countries, the Ministry of Religion or religious police monitors this process. If a police officer is, for example, on the street and sees that during the time of Muslim prayer someone is not praying, they may deal out a blow with a stick, even if it is a woman. This is very strictly controlled.

"Libya is a hornet's nest. Once stirred, it cannot be put back together"

—In May 2012 a law was introduced banning praise of the Gadhafi regime and critique of the revolution. However, recently the BBC reported repeal of this so-called Act 37. Do the locals, at least amongs themselves, speak about Gaddafi?

Nobody is talking. Local people are intimidated. Former supporters of Muammar Gadhafi are few, and the city where the tribe associated with Gadhafi lived is wiped out. So, of course, no one even remembers.

This is normal for this kind of revolution, when the power comes from the outside and trys to destabilize the situation.

170,000 are officially recognized as killed in Libya and 530,000 missing. It is clear that these "missing" are dead. If we analyze these numbers, it is around 20% of the population.

The situation is difficult, but the war continues—every day we hear gunfire, even from tanks and anti-aircraft guns.

—How do you move around in Libya?

—In various ways, depending on where you need to go, and in what area you are located. In armored vehicles, cars, ambulances or on foot.

In Libya they cannot bring order, and probably will not. A million people are from the tribe of Gadhafi, incuding Gadhafi himself; they married their sons to girls from the other tribes, who were thus joined to his tribe. So at least half the population in this nation is hostile to the provisional government.

And what do blood feuds and family ties mean to the Arabs? For their family, they are ready to take revenge on anyone. Therefore Libya is a hornet's nest: once stirred, it can never be put back together.

"I once gave a child from the slums a handful of candy, he began to rustle the wrappers open… and threw the candy away”

—And

why the mission in Muslim countries, why Africa?

—I served nine years a priest, and the first time I really felt like a pastor of a flock, oddly enough, was is in Africa. At home our attitude to the clergy is stereotypical. Most believe that the priest "should, and must." Others believe that the priest exists only for the fulfillment of their desires and personal whims. Still others come to church, they listen to the priest, and decide: "His advice does not suit me, I'm going to look for some other advice and another priest."

In Africa, it struck me that people do not play double standards, do not look for something for themselves: "I stand before the priest as one person, leave the church as another person, and tomorrow I will be a third." No. Seeing that the priest came to them, they try to use it for the good of their soul, and cleave to grace, to the Holy Spirit. How they greet me and how they see me off is hard to describe. I want to return to them time and time again.

Another aspect which appeals to me is Africa itself. People there are not spoiled by the permissiveness of the modern world. We find it hard to understand what love is in a larger sense, mutual understanding, and respect—for them it is the norm.

There was one incident in Pakistan. The UN built free housing for slum dwellers. But no one moved in, and the UN could not understand what was going on. Imagine what would happen if we built a house and said: “Whoever wants to can move in.” There would be a fight for it.

We went to the slums with four local residents. I came to the locals and asked them, why isn’t anyone moving in? I was told—"How are we going to move, if the house is built for 5000, but 10,000 live here in poverty? I will live in good conditions while my neighbor, my brother, will live in the slums? I would not be able to sleep. If you want to help us, build a home for all of us.”

I tried for two weeks to explain to Westerners the reason for the refusal to move from the terrible slums into a new house, but they never understood.

There was another story in Sudan. Each day we were given a ration: a bottle of water, a tomato, an egg, cream cheese, jam, and honey. I would walk out of the hotel with these rations, and the children who were playing football would run up to me thirsty. I, with my own mercantile mind, said goodbye to the water: "Well, I will roast in the sun today without it."

The eldest took the bottle, opened it and gave it to the youngest to drink, and so they all drank a little and gave me the remaining water. They even tried to say “thank you,” in English and then ran to play more football. I stood there and thought, "How can this be?"

Once I gave a child from the slums a handful of candy. He began to rustle open the paper wrapper, and then threw candy on the ground. Again he asked me, "Give me something else." I took a piece of candy, opened it and ate it in front of him, took out another, and gave it to him. He ate three. It turned out that the children had never seen chocolates.

I told this to a representative of the United Nations, who I know well. He was so struck by this that we gave away 800 kg of sweets to children!

But not only have many never seen sweets, they have never seen money, never mind the means to receive an education.

I have a dream to go to Africa for good and teach the children. Soon I hope to get a pilot’s license, because it is convenient to move, organize a fund to help African children, and we will bring them pens, paper, sweets, and clothes. There are very few literate people—only in the capital city.

"Every time I travel in these countries I appreciate, more than ever, the simple things"

—What exactly is the mission of the Orthodox priest in Islamic countries?

—First of all, a priest, who is going on a mission to such countries should have a very strong desire to go there, and be tough. Because after arriving there, you face all sorts of difficulties ranging from climatic conditions that affect human health to life-threatening gunfire.

We must remember that this is not Europe, where there there is time to serve and then to rest; where it's safe. In 22 days in Libya I served 18 liturgies, and afterwards had hours of conversations with my compatriots.

General pastoral care abroad can be divided into stages. The first is meetings with people—this is the stage of silence. You listen to people talk all the time. This is the so-called silent sermon. People appreciate that the Orthodox Church sent them a priest. True, the word "come and sing us songs" is said more often than "come and serve us."

The second stage involves actaully talking about God and prayer, because people mostly are already going to church and face problems.

Therefore three things are important for priests: faith, love and endurance. And if we are in a war, psychological and physical preparation.

And we must remember that first and foremost we go to serve our own people, to come to our own churches as Christians.

By the way, when we managed to get permission to serve in

Libya for Easter, over 200 people attended. Imagine the

armies shooting, we are in the church, and all two hundred

people with one voice sincerely pray “Christ has

Risen.” It was indescribable.

Every time you get in those countries you appreciate, more

than ever, the simple things—water, bread,

peace—and those Gospel values—mutual support,

love, gratitude, fidelity, as the Lord says.

P.S. As the sentence has not yet been enforced, the Ukrainian prisoners ask for our prayers for their release and repatriation.