There is a Russian proverb: Odin v pole ne voin—“One man on the field isn’t a soldier,” or “One man can’t win a war alone.” But Fr. Seraphim Galik has shown that one soldier can win.

God alone knows how many lives Fr. Seraphim has saved, how many hours, days and months this father with many children of his own has spent standing in front of abortion facilities in order that little children would appear in other families, too. One day an old woman came up to him and said, “It’s so good that you’re standing here. I killed my child and even now 40 years later I am still crying.” Fr. Seraphim has dedicated his life to helping assure that there will be as few such women as possible.

Fr. Libor Seraphim Galik.

Fr. Libor Seraphim Galik.

—No, my mother gave me the Czech name Libor. My last name is Galik. Libor is my legal name. And in the Protestant church I was baptized as Libor, but afterwards when I converted to Orthodoxy, a priest told me that I had to be baptized, and he asked my name. I said, ‘Seraphim,’ because I revere St. Seraphim of Sarov very much. After baptism other priests told me that it hadn’t been necessary to baptize me again. So for that reason I use both names—Libor and Seraphim.

—Fr. Seraphim, how long have you been involved in protecting the lives of unborn children?

—In 2002, when I was in the Theology Department in college (university), I wrote my dissertation about abortions and demographic problems. Then I met a priest from New York, who told me about his experience working with abortion facilities, and he suggested that I try to do the same thing in our country, in the Czech Republic, in the city of Brno. On May 8, 2003, I prayed, “Lord, give me the strength not to be afraid of people who have betrayed Thee and who have not been faithful to Thee.” Three days after this a priest[1] from New York named Philip Reilly gave a lecture in Prague, and said that people who either want to murder or murder a child in the womb are condemned to the eternal torments of hell. These words called to me, to my Christian conscience. Philip Reilly said, ‘It is important to pray in front of the clinics where the doctors are murdering children, so that we would remember what is going on there.’ To the question of why, from the very beginning, so few people carry on this spiritual battle, Fr. Philip answered, ‘It happens because people are afraid. But the Mother of God and St. John the Apostle stood under the Cross. And we need to be there, too, where the Cross is.

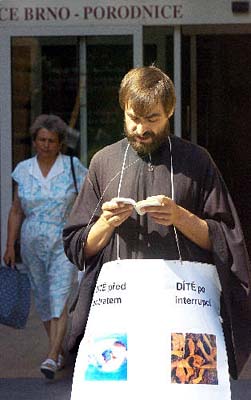

Then I returned to Brno, put on the black garments of a priest and took a small Bible with the Psalms, and I began to read them in front of the hospital. On the first day nothing happened; on the second day they called the police on me. I said that I was speaking in support of women after abortions who had post-abortion syndrome. Then every day it was either the police or different members of the press: newspapers, radio, or television. They thought if they said disparaging things about me on television that I would get scared and go away. But that didn’t happen. It’s a good thing that people saw a priest referring to abortion on television as murder.

For the first few months, when I would return from this clinic, I would be all tired out from the bad things they said, from the bad people—most of all from the workers at the clinic. I felt their hard hearts. Because of this, when I would come home to have dinner together with my wife, I would collapse and go to sleep for a couple of hours. Later it wasn’t like that, but at the beginning I was exhausted. Maybe it was some kind of temptation from satan, that I felt this evil more than other people, more than the people who were helping me.

Then there were the first two marches in Brno. The first time 50 people came, the second—100 to 150. Then 25, 20, 15 people took part. In the last few years there have only been 10 people. In the first year we had these marches every two weeks. The best time was at the beginning, when the officials and the clergy didn’t say anything against us. That was something new. At that time, our Czech deputies (members of parliament) wanted to forbid abortion. Later—maybe a year and a half or a year after that—the deputies in our parliament threw up their hands. By their bad example they influenced the rest of the leaders, bishops and priests. People gradually stopped helping. I continued my daily battle on the street, except on Saturdays and Sundays. I think that it would have been better if it hadn’t gone so badly with our deputies, and then with the officials, bishops and priests. If there are leaders who defend life, then the people will also defend it. But if the leaders remain silent or are against it (secretly against it, not openly), then the whole nation will perish.

A march in Brno.

A march in Brno.

My friends thought that a thousand people would come to me, but they didn’t. That showed the truth about what kind of Christianity there is in my city and in our country. It is a very frightened Christianity—people talk about love, but they don’t want to defend love if someone is against it. Jesus Christ said that the people who are afraid will be in the first place in the lake of fire—then the other sins. All sins begin with this. When the Apostle Peter said, I don’t know Christ, he was afraid. If he hadn’t repented, from this sin would have come other sins, there would have been more and more sins. We have to overcome our sinful body, our sinful society—conquer it and then gain the victory over satan and all the demons. They attack, too, but we shouldn’t be afraid of this.

—And what is your attitude towards a union with Catholic organizations in the fight against abortion?

—In this battle, we ought to work with other Christians, because this is murder. Historically, the Czech Republic was Catholic for many centuries, so without working with Catholic laypeople, I can’t do anything. There were Catholic Pro-Lifers praying in front of the abortion place, with Catholic prayers. But I used my own prayers.

—Have they used physical violence against you? Have they caused any serious injuries?

—They must have done it about five times. They broke a cross two meters high. Then I took a cross three meters high, and they didn’t break that one. I had a megaphone in a tree, and they broke the tree and damaged the megaphone. They assaulted me, poured paint on me, spat on me, and doused me with water from a hose, but it was hot, so nothing bad came of it. That was only three times in nine years. They said that they were going to beat me, they wanted to frighten me. Before arriving at this clinic I prayed at night that the Lord would help me, that I wouldn’t be afraid. I prayed when I came to this street that these people wouldn’t be there. And the Lord gave me a sign: you need to come when they aren’t there yet. Later, when I would come to this street and they wanted to assault me, suddenly a police car would arrive, and they couldn’t beat me up. That happened several times—always by accident.

—You were talking about the politicians who didn’t want to help you. Is it worth constructing a dialog with the authorities, some kind of interaction with the people, in order to receive their support?

—I only knew one deputy of the Czech Parliament who used to talk with me and who defended me in front of the bishop at the time when some priests wanted me to stop this activity. Under their influence the bishop wanted to forbid me, because he was afraid, but the deputy wrote that this was a good thing, and so my bishop did not forbid me.

Once some people from Slovakia wanted me to drive around the cities of Slovakia with them and speak in front of the abortion clinics in Slovakia with a megaphone, while showing large photographs of murdered children. In one town they showed it on television, and the Slovakian Orthodox bishops saw it. One archbishop got scared and told my bishop in the Czech Republic that I could never travel to Slovakia and that I couldn’t speak anything against abortions. My bishop was afraid of the archbishop and told me that I couldn’t travel to Slovakia. When that archbishop died, they put another one in his place, and my bishop told me that now I could travel to Slovakia and speak against abortions. That’s the way it is sometimes—sometimes even death helps.

In Holy Scripture it says that we should give birth to children, so that there would be many of us. I fear that if a person simply doesn’t want to have children, he or she also will be punished by hell. But for murder comes punishment by means of war, because when human blood is spilled, the blood of the murderers also will be spilled. It is the Lord Who said this. This means that following the murder of a child there will be war. And in order to avoid war or punishment of death from the Lord, we have to fight against abortions, so that children would be born. Today the faithful don’t believe the Lord, that they will have money to support children, that they will have a large apartment and so on. They have forgotten that their forebears had smaller apartments and less money. People have to learn this; it’s life in the faith.

—It seems to me that we have to expend more effot on preventing abortions, that is, on the upbringing of children. Very few priests talk about the harm of abortions, about how they can’t be allowed. But there is a Greek monk, Metropolitan Nektarios of Argolis who is not afraid to speak even to 8-9-year-old children on this topic. And the children remember these conversations for their whole lives. Have you had similar experience of working with children?

—We always had children in our marches against abortions—my own children and children from other families. They see the photographs of murdered children and ask, “What is that? Who is that?” They know right from childhood that abortion is murder. I think that all children should know this. If it is possible to talk about this in the parishes, then let all priests talk about it; if in the schools, let it be in the schools—it isn’t all that bad.

—Often priests complain about not having enough time, but this is an important matter, and we need to find the time for it.

—How many parishioners in the church? If some families want to go to the school—let them go. Maybe it happens that one priest isn’t enough for a lot of people, but there are other people who can help this priest.

—How many women have you talked out of having an abortion?

—Once I was talking with twenty women, who told me that they thanked me, that they weren’t going to get an abortion. These women spoke openly, others have not said anything, so I don’t know whether I have helped anyone or not. It’s a mystery of the Lord—He knows, I don’t know. But you have to speak out against abortions. That it is murder is evident in the photographs of the child in the mother’s womb. Even an atheist sees murder. In Russia, even atheists are against abortions, because they don’t want a genocide of the Russian people. They saw the photographs and they said, “Yes, that’s murder.” You didn’t have such photographs before, but now there is evidence for the materialists and for the atheists—these photographs.

Path to Orthodoxy

—Fr. Seraphim, how did you come to Orthodoxy?

—I came to Orthodoxy by a long route—through Protestantism and Catholicism. That was easier for me, since one was a little bit similar to the other. I didn’t have any acquaintances who were Orthodox. I was born in 1966 in Prague. Now I’m a priest in the Orthodox Church. My wife and I have six children. When I was born, my parents didn’t baptize me—they were atheists at that time. As a child I never participated in religious ceremonies, I never went to any church—Orthodox, Catholic, or Protestant. Maybe, when I traveled to some city or other where there was an old church, I would drop in as a tourist, but I never went to a service. Once I ran into a group of Protestants, and they said to me, “If you want to believe in the Lord, pray, and perhaps the Lord will show Himself to you, that He exists.” Until 1984 I did not believe in the Lord and had never held the Bible, the Koran, or any other religious books in my hands.

I remember how till about age six I used to pray with my mother, grandmother, and my grandmother’s sister: “O my Guardian Angel, keep my little soul, so that it would always be good and always love the Lord God. Keep my soul and body, O Angel, my Guardian.” My suffering after my parents’ divorce forced me to think: was there a God, or is He only something from fairy tales?

Then someone told me that, on the basis of all that exists, there should be Someone Who is the beginning of everything. I realized that this, perhaps, was the Lord. But I didn’t want to associate with the Lord. I didn’t want to say “Please” to someone unknown, so as not to have to say “Thank you” later. But when I was 17 or 18 years old and couldn’t sleep, I decided to say something to the Lord, and then to say “Thank you.” Once at night, when everyone had already gone to bed, I went down into the dark cellar and, standing there, I said, “Lord, if you exist, help me!” I didn’t see anyone, but I felt someone bring me to my knees, so that I would not be standing, like some master, but so that I would be on my knees. And I felt then the Lord’s tremendous love for me—the Lord, Who was still unknown to me. I didn’t see Him, but I felt that it might have been an angel who brought me to my knees. And I felt in my heart that the Lord loved me more than my mother, father, or anyone—more than any person, far more than mothers love their children. From that time on I know that the Lord exists, that He loves me, and that it is good to be with the Lord. That’s the way I stopped being an atheist in 1984.

—And before that, had you thought about God or about the meaning of life? How did you relate to people who went to church and believed in God?

—I believed in evolution, I believed that we came from apes. I didn’t meet a single schoolchild in elementary school who believed in God. When I was in high school (from 15-18 years old)[2], I heard that—out of 25 people in my class, maybe three or four believed in God. But they didn’t talk about the Lord; they talked among themselves, about how there was a church and someone went to it.

—You have been a Protestant, and a Catholic, but you came to Orthodoxy. Was your way to Orthodoxy long?

—Once, when I was in the forest looking at birds, I had to swim across a river. I didn’t know that there was a dam there, that they drained the water there, and I found myself in this river when they had opened the gates and the water was coming. The water caught me up, and in the water were large trees. I was under these trees and couldn’t breathe. I knew that I was going to die, but I didn’t want to die and I said, “Lord, help me! If You help me, I will listen to You, obey You.” He saved me, and I’m alive. Later I related this to a Protestant minister and asked him to baptize me, and I became a Protestant.

I didn’t know anything else. I had one Protestant friend, and he acquainted me with other friends. I didn’t know history, I didn’t know what the difference was between Protestantism, Catholicism, and Orthodoxy—I didn’t know anything. I only took the Bible in my hands, and sorrow went away. I didn’t understand the words. But after I was baptized, when I read the Bible, then I began to understand. That was like food for me. I read all the time; I always had the New Testament in my pocket. My mother was really afraid that I was going to become a Catholic priest—they live without a wife or children. When she saw that I was reading the Bible, she threw it all the way across the room. I read the New Testament secretly in a place where I could lock the door—that was in the bathroom! When I wanted to read the Bible, I had to go into the bathroom and lock myself in there so my mother wouldn’t see. I read the whole New Testament by locking myself up in the bathroom.

I was fascinated by biology, and at first I thought that it was possible to unite evolution and faith in the Lord. When I began to read the Old Testament about the Flood, and the other books, I saw that it is impossible to believe in the Old Testament and in evolution. I had already studied First-Year Biology in college[3], but I left near the end of the first year. I left university, and in only 14 days I was taken into the army for two years.

“I was afraid to go into the church where the Mother of God is held in esteem.”

In 1988 in my last six months in the army they sent me to the psychiatric clinic twice, because I was talking to the soldiers about the Lord, and they thought that I was abnormal. But there was nothing wrong or sick about me, and they sent me back from the hospital into the army. But they didn’t want to take me into the army, and they sent me where there were no soldiers, only coal. At this time I was a Protestant, but Protestants don’t respect the Mother of God—Catholics and Orthodox respect the Mother of God. So I was afraid to go into a church where they honor the Mother of God. I stepped into that church very cautiously. Later I began to believe that it wasn’t a sin to venerate the Mother of God. I, a Protestant, wanted to become a Catholic.

Then I met a person who said that he was Orthodox, but didn’t say anything more. And I wanted to know more about this teaching. I found out from one person that there was a theological school in Slovakia where you could study Orthodox theology, where they would tell you what Orthodoxy is. And they took me there. In 1994 I became Orthodox, and a year later I was ordained a priest. The parish was a long way from my town of Brno, on the border with Poland. That was a very difficult time.

—Wasn’t there a single Orthodox person there?

—Not one. There were Czechs there who said to me, “Father, we don’t need to go to church. The priest who was here before you only prayed the “Our Father” and went home. You do the same thing, too—we don’t need the Sacred Liturgy.” But I was told that it is necessary that the Holy Liturgy be every Sunday. But they said, “No, don’t—once a month is enough.”

—I don’t have a person who could be an example to me. My flock is very small—just my family. And there was one other family—Adventists who became Orthodox. But later they took offense at me because of their son, who was getting poor marks in school. They wanted advice from a Catholic priest. And he told them that they had to go to a psychiatric hospital. I said to them, “Don’t go—I worked in a psychiatric hospital and it was not a good experience.” I worked there for half a year, before I was a priest, and I saw these people. I didn’t think that pills could help them.

—Father, it’s very hard to live with relatives who don’t believe in God—you feel very sorry for them, but you can’t do anything. Do your relatives believe in God?

—When I myself came to believe, then I started to be afraid that my parents, brother and sister were all going to go to hell. I was very afraid of this and I began to pray for them; I fasted, I didn’t eat anything at all. I continued to pray for them in the army, too. Once when I was on leave I came home to my mother and prayed for her, for my brother and sister, that they would begin to believe in the Lord, that they would not go to hell in the future. And suddenly I heard a voice that said to me, “Ask for something” and I said, “Lord, please, that my parents and brother and sister and friends would be saved, that they would believe in Thee and not go to hell.” From that day on I wasn’t afraid any more. Many, many years passed before my father began to believe in the Lord. But remember, for example, Blessed Augustine. His mother was a Christian, but his father was not a Christian—he forbade his son to be baptized. St. Monica prayed for her husband and for her child. And before his death, her husband began to believe in the Lord and was baptized. And her son, also, after 20 years of his mother’s prayers, was baptized, then became a bishop and helped many people come to the Lord.

—Father, may I ask what means you have to live on? Do you have any donations? Do they sell candles in the churches?

—In the Czech Republic we have a small salary from the government. If a person doesn’t have a church, there are no donations; if he has a church, then there are candle donations, but that is very little. You can’t live on it, because we have in a parish, for example, maybe two or three people or four or five—very few. It isn’t even enough for bread for a week.

—And how many children do you have?

—Six children.

—How do you raise them?

—On this small government salary. I don’t smoke, I don’t drink, I don’t have a car or a dacha.

—Father, when you were younger did you have any bad habits?

—No, I didn’t. I was a proper student. I was an atheist. I was the school valedictorian. I was an honors student.

—Has it ever occurred to you to move to Russia or Greece, where there is more respect for priests?

—I don’t know. I have only visited Armenia, but I don’t know Armenian. I’ve been to Russia twice—to St. Petersburg and to Moscow, and I’ve been to the Ukraine twice.

—And how did you manage to learn Russian so well?

—I studied on Skype. Gleb from St. Petersburg talked with me every day on Skype. I listen a lot to recordings, the lives of Russian saints. We don’t have any Orthodox literature in the Czech language. It’s only possible to find out about Orthodoxy from Catholic books. I used to read Catholic books about Orthodoxy. Later, when I was already a Pro-Lifer, I read Russian ones.

—Do you yourself write books, Father?

—I’ve written a diary about my fight against abortions, but it’s in Czech. One person that I worked with made 300 copies of this book and then I gave them out to my friends.

I know that our fight against abortions is not only a fight against something bad in our state; it is a fight against those who are paving the way for the rule of the antichrist. As Elder Joseph of Vatopedi said, “The coming of the antichrist to power is being prepared, and there will be a great war against the family. But the Lord will have mercy on us.

The Church has to be pure, to be prepared for this war with the antichrist. Now, if it were the rule of the antichrist, how many martyrs would there be? Most Christians would do the same thing as the Apostle Peter, they would say, “I don’t know Him,” and “I’m afraid.” And what would become of them at the time of the antichrist, if they get frightened? There will no longer be any forgiveness, there will be no possibility of going to confession. Therefore the Lord will have mercy, according to the words of Joseph of Vatopedi. During this war, the enemies of life will not unite, but just the opposite—they will be against each other. Many people will perish, but after this war it will be better, because these enemies of life will have been killed—they will kill one another. There’s that hope, but there is no joy in the fact that there will be some kind of war. When I became acquainted with this information, I was very frightened, because I don’t want a war. But the holy fathers say that if there weren’t this war, there would be no repentance. Now there is no repentance—you have the murder of children. People are going to hell without repentance; they are going to hell for all eternity. With repentance, it will be better. So that’s why such horrible events lie ahead.

These elders have said that you have to fear sin, so as not to sin. Now we are saying openly that abortion is murder, we are showing these pictures, these photographs. Once, when I was standing in front of a clinic, an old woman came up to me and said, “It’s so good that you’re standing here. I killed my child and even now 40 years later I am still crying.” She gave me some money and said, “Don’t stop.”

Earlier, during Communist times—and even now—they told people that it wasn’t murder: you’re going to the doctor, everything is fine. If your tooth hurts, you go to the doctor. So people think: “I’m a good person, I haven’t killed anyone.” But he has killed and doesn’t want to feel like a murderer. When he comes up against this photograph, he sees a child who was killed in its mother’s womb. The thought comes to him: Am I a murderer? No, I don’t want to be. But later, when there is a war, people will die, and he might remember that he saw someone with a photograph of a murdered child, and now he sees murdered adults, and thinks: I understand—it is a punishment from the Lord. I killed, now they are killing me. If he didn’t have this information, if he hadn’t seen this child in the photograph anywhere, he would not have any means of repenting when it is very bad, when there is war. That’s what I think.