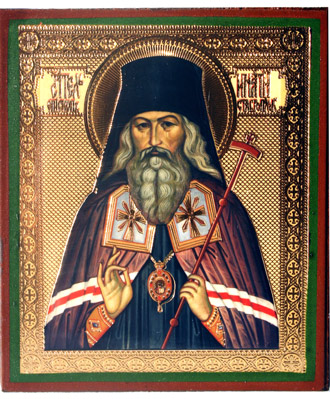

Bishop Ignaty (secular name, Dimitry Aleksandrovich Brianchaninov; 1807-1867) was an outstanding ecclesiastical writer and ascetic of the nineteenth century. He had no special theological education. He studied at the main engineering college in St. Petersburg and in 1824 graduated from it, receiving an officer’s rank. During the following four years he fulfilled various obediences as a novice in several monasteries, after which he took monastic vows and was appointed in 1883 as Father Superior of the St. Sergei Hermitage of the St. Petersburg Diocese. He gained profound experience in the knowledge of God by studying the works of the holy fathers. In 1857 he was consecrated bishop of the Black Sea and the Caucasus. In 1861 he retired for reasons of health and settled in the Babaevsky Monastery of St. Nicholas. Besides his feats of prayer and extensive correspondence with his spiritual children, Bishop Ignaty devoted much of his time during these years to literary work. The reader of his works discovers in their author a pastor-ascetic engaged in an intense spiritual combat and who is tragically depressed by setbacks in this struggle. The main motivation behind his ascetic works is his awareness of the damage done to human nature by sin. He wrote: “Our nature is contaminated by sin so that it is quite natural for it to generate unnatural sin” (Essays of Bishop Ignaty Brianchaninov, 3rd edition, St. Petersburg, 1905, Vol. 5, p. 435). “The Christian discerns within himself the human Fall inasmuch as he can see his own passions. Passions are the sign of the sinful mortal disease which afflicts the entire human race” (1.528). “In order to achieve success in the spiritual life, it is necessary for our passions to reveal themselves by coming to the fore. When passions reveal themselves in an ascetic he comes to grips with them” (1.345).

These ideas are further elaborated in all of the works of Bishop Ignaty. In all of his writings on any subject, including practical pastoral advice, Bishop Ignaty takes the reader back to the understanding of the root cause of the misfortunes of the human race, which helps to combat each and every concrete manifestation of sin. Thus defining monastic self-reproach, he points out that it is “a good cause, counterposed to and counteracting the morbid condition of our fallen nature …” (1.345). Elsewhere he writes: “Speaking of books, one should say … that it is necessary to choose among them not the most elevated ones, but the ones that are nearest to our own condition, which describe actions pertinent to ourselves” (2.292). “When a person does not arrange his responsibilities in due order, does not attach to each of them the priority it deserves, then the fulfillment thereof cannot yield virtue, but will only produce sinful mistakes which are all the more dangerous because they have a virtuous appearance” (4.421).

The works of Bishop Ignaty reveal the remarkable literary gift of the author. Being confined to the boundaries of theological-ascetic reflection, he never expressed his thoughts in trite terminology, reducing the spirit to stereotypes, but always finding ways to give new life to concepts that had long become standard elements in theological schemes. This is how he describes, for example, the fruits of the Church’s prayer: “Unity is above earthly sensations; there is something heavenly in it; it includes an anticipation of the life to come, in which the spirit will unite” (4.338). His literary style conforms to the spiritual realism of ascetic edification. The most important element is the thought; it is not built and developed by means of terse logical forms, but like a sculpture cut from a rock is resolutely freed from everything that conceals it from view. But with all that, when there is a need to convey some more sublime spiritual notions, Bishop Ignaty makes skillful use of literary imagery: “Only he can see the fruit of the Spirit upon the tree of his soul who had nurtured this fruit—holy and tender—using much patience with courage” (2.9). “Having grown old and weary through much suffering while being barren, when it finally yields, beyond all hope, a spiritual fruit, the souls says, after the manner of Sarah, God hath made me to laugh (Gen. 21:6), that is it has been granted an unexpected and inalienable joy of betrothal with the joy eternal” (5.446).

The literary style of Bishop Ignaty is distinguished not only by his use of aphorisms, compressing a thought into just a few words, but he manages to convey in these terse periods spiritual experiences of extraordinary force: “Woe is me if the spirit, having parted with the body, dies the eternal death” (5.458). “If, wounded by an enemy arrow, you suddenly feel yourself contaminated by passions, do not despair!” (5.59). All this makes it possible to speak of a proximity between the words of Bishop Ignaty and poetic literary genres, the difference being that instead of going into the aesthetic aspects of sensual experiences, he conveys to the reader a charge of spiritual energy and the will to repent as uniting with God.

Fr. Mikhail Dronov

* * *

Enter into thy closet, and when thou hast shut thy door, pray to thy Father which is in secret; and thy Father which seeth in secret shall reward thee openly (Mt. 6:6).

The Lord Who has given us this commandment concerning secluded prayer very often resorted to such prayer Himself during His earthly life, as we learn from the Gospel. He had nowhere to lay His head, and therefore more often than not it was not in some secluded cell, but on remote mountain tops and in the shade of vineyards that He said His prayers.

Before His Passion at the cost of which the salvation of the human race had to be bought the Lord went to pray in the secluded Garden of Gethsemane. There the God-Man kneeled down and prayed; and being in agony, He prayed so earnestly that His sweat was as it were great drops of blood falling down on the ground.

The Garden of Gethsemane was of centuries-old olive trees, so that even in daytime and bright sunlight there was deep shadow down under the trees, and at that particular moment it was enveloped in the pitch darkness of a Palestinian night. There was no one to share with the Lord His solitary prayer: His disciples dozed off nearby and all of nature was in slumber. And it was to that spot that the traitor led the armed multitude, for he knew only too well the place and the time wherein Jesus liked to say His prayers.

The darkness of night hides objects from an idle gaze and the silence of night does not distract one’s mind. In the still of the night one can better concentrate on prayer. The Lord preferred to pray in seclusion and at night, and He did so that we not only obey His commandment concerning prayer, but also follow His example. Was it really necessary for the Lord Himself to pray? While being as man with us on earth, He, as God, remained in constant union with the Father and the Spirit, sharing with them the one Divine will and one Divine sovereignty.

Enter into thy closet, and when thou hast shut thy door, pray to thy Father which is in secret (Mt. 6:6). Let no one know about your prayer, neither a friend, nor a relative, nor vanity itself which lurks in your heart and prompts you to let your feat of prayer be known to someone, at least by just dropping a hint about it.

Shut the doors of your cell to people who come for idle gossip and in order to steal from you your prayer; shut the doors of your mind from idle thoughts that will come to distract you from prayer; shut the doors of your heart to sinful feelings that will tempt and try to defile you and go and pray.

Dare not to offer up to God prayers of many fine words which you may compose no matter how powerful and touching they may seem to be: they are but the product of the fallen mind, and being a defiled offering, they cannot be accepted on the spiritual altar of God. And while admiring the fine expressions of the prayers you invent and mistaking the action of vanity and voluptuousness for the consolation of consciousness and even for the action of grace, you will drift far and away from real prayer and that at precisely the time when it would seem to you that you pray in abundance and have already achieved a degree of perfection pleasing to God.

A soul embarking upon the path leading to God is plunged in profound ignorance of everything Divine and spiritual, though it may have in abundance the wisdom of this world. Because of this ignorance it does not know how and how long it should pray. To help this soul in her infancy the holy Church has established Her rule of prayer.

The objective of the rule is to furnish the soul with the necessary amount of prayerful thoughts and feelings which are also correct, holy and truly pleasing to God. It is with such thoughts and feelings that the grace-giving prayers of the holy fathers are suffused.

For prayerful exercise in the morning there is a special set of prayers known as morning prayers or the morning rule; and there is another set of prayers which are to be said before retiring to bed in the evening, which are known as the evening rule. A special set of prayers is to be recited by persons preparing for Holy Communion, which are called the Holy Communion rule. People who have decided to devote the greater part of their time to pious acts (monks) recite around three o’clock in the afternoon a special set of prayers, called the daily or monastic rule. Some recite daily several kathismata, read several chapters of the New Testament, and make several bows, and all these things are also called the rule.

The rule! What a fitting name borrowed from the nature of the effect produced upon a person by prayers which are called the rule! The prayer rule sets the soul unto the right and holy path, teaching it to worship God in spirit and in truth (Jn. 4:23), because being left unattended, the soul would have been unable to find the right path of prayer. Being afflicted and blinded by sin, the soul would keep straying from that path, often into pitfalls, such as distraction or idle dreaming, or wander after all sorts of empty and deceitful mirages of elated prayerful states invented by vanity and lust.

Prayer rules help keep the one who prays in a salvific disposition of humility and penitence, teaching him constant self-judgment, nourishing him with true emotion and fortifying him with the hope pinned upon God, Who is Good and All-Merciful, and giving him the joy of the peace of Christ, of loving God and neighbors.

How lofty and profound are the prayers before Holy Communion! They put into order and adorn the chamber of one’s soul with wonderful thoughts and sensations that are pleasing to God. These prayers present a majestic picture of the greatest of the Christian Sacraments, and in contrast to this height they depict, vividly and truly, the shortcomings of man, showing his infirmities and unworthiness. Shining from these prayers like the sun from the sky is the inscrutable goodness of the Lord thanks to which it pleases Him to be closely united with man even despite man’s unworthiness.

The morning prayers seem to emanate the cheerful vigor of daybreak: seeing the rays of the material sun and the light of the earthly day a person learns to aspire after the vision of the supreme spiritual Light and the Day that is without end which emanates from the Sun of Truth, from Christ.

The brief rest in sleep at night offers the image of the long sleep in the dark grave. And evening prayers remind us of the approaching passing into eternity, help us take stock of everything we did during the day, and teach us to offer up to God the confession of our sins and repentance.

The prayerful recitation of the Akathist to Our Sweetest Lord Jesus, besides being worthy in its own right, offers excellent preparation for prayerful exercise with the Jesus Prayer, which is as follows: “O Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy upon me, a sinner.” This prayer offers nearly the only consolation to those who have achieved perfection in ascetic feats, who have achieved Christian simplicity and purity, for whom any excessive abundance of thoughts and abundance of words is but a burdensome distraction. The Akathist shows what thoughts can accompany the recitation of the Jesus Prayer, which strikes one at first as being too dry. The Akathist depicts only the plea of the sinner to be forgiven by the Lord Jesus Christ, but this plea takes on a variety of forms to suit the infant state of mind of those embarking upon such acts. It is just like how they feed infants with soft and palatable food.

The Akathist to the Mother of God glorifies the Incarnation of the Divine Logos and the greatness of the Theotokos who is called blessed by all generations (Lk. 1:48) for giving birth to God Who became man. The Akathist depicts, like on a grand canvas, with countless and marvelous colors shades and traces of the great Mystery of the Incarnation of the Divine Logos. And just as the right lighting helps to enliven a canvas, so also the radiance of grace lights up the Akathist to the Mother of God. This radiance has a particular effect: it enlightens the mind and fills the heart with joy and good news. The incomprehensible is accepted as a matter of course thanks to the miraculous effect produced [by the words of the Akathist] upon the mind and the heart.

Many devout Christians, especially monks, observe a very long evening rule of prayer, taking advantage of the quiet and darkness of light. They add to the evening prayers readings of Kathismata, the Gospel, the Apostol, recitation of Akathists and the making of bows accompanied by the recitation of the Jesus Prayer … These servants of Christ shed tears in the silence of their cells, offering up to the Lord their fervent prayers … In joy and with a wakeful spirit, with a sense of extraordinary concentration of the mind upon things Divine and readiness to do all manner of good deeds, servants of God meet the new day, following the night which they had spent in the feat of prayer.

One should in no way be in a hurry while reciting the rule or making bows; both should be done without any haste and with all possible concentration. It is better to recite fewer prayers and make fewer bows but with utmost concentration rather than do these things in abundance but in an absent-minded manner.

Choose for yourself a rule you have the strength to observe. What the Lord said about the Sabbath, that it is for man and not the other way around (Mk. 2:27), can and should be applied to all devotions, including the prayer rule. One can say that the prayer rule is for man and not the other way around; that the rule should help man attain spiritual perfection and not be a cumbersome burden, crushing man’s bodily strength and tempting the soul. Nor should it ever give grounds for pernicious arrogant pride, or for ruinous condemnation and humiliation of fellow men.

The prayer rule, chosen prudently to suit one’s strength and manner of life, offers great support to those seeking to attain salvation. Observance of the rule at the proper times of day and night turns into a habit, into a natural and indispensable requirement. And as soon as the one who has acquired this happy habit comes near the place where he usually performs the rule, his soul is filled with a prayerful mood, and before he can even begin reciting his prayers, his heart is filled with emotion and his mind withdraws into his inner chamber [the heart].

“I prefer,” said one great abba, “a rule that is not long, but is constantly observed, to a long one which is given up after a short while” (St. Mathoi, Alphabetic Skete Patericon). And this is what always happens when one chooses a rule that surpasses his strength: gripped with enthusiasm, a person keeps the rule for some time, paying, as one can expect, much more attention to the quantity than to the quality, and then his strength runs out, being exhausted by the exploit surpassing his strength, and then he is forced to reduce his rule more and more.

It often happens that having heedlessly chosen too difficult a rule, people engaging in ascetic acts simply give up and stop praying. When this happens, and even when the rule is reduced, such a person is gripped with doubts, his soul is plunged into disorder and he becomes despondent. This feeling continues to grow, causing flabby indifference, and then the person plunges into a life of idle distraction and commits with indifference some of the worst of sins.

Thus, having chosen for yourself a prayer rule in keeping with your strength and spiritual needs, try and keep this rule with all due care and constantly: this is necessary to keep up the moral strength of your soul, just like you have to take every day at certain hours a sufficient amount of healthy food to maintain your bodily strength.

St. Isaac the Syrian says:

It is not for abandoning Psalms that we shall be adjudged by God on His Judgment Day, not for abandoning prayer, but for the entry of demons into us which follows. When demons find the place, they come in and shut the doors of our eyes, and then they use us, as their instruments, to perform forcibly and uncleanly, with the worst of vengeance, everything forbidden by God. And because we abandon a small [rule], which grants us Christ’s intercession, we fall under the sway of demons, as one most wise abba wrote: ‘He who fails to submit his will to God, such a one shall submit unto his adversary.’ These rules may look small to you, but they shall be the walls protecting you from those who want to take you prisoner. The keeping of these rules within your cell was most wisely established by the makers of the Church rule, by a Divine revelation, in order to safeguard our life (Homily 71).

The great abbas who always remained in a state of prayer from an abundance of God’s grace did not discontinue their rules of prayer which they were used to performing at certain hours of day and night. And we see many proofs of this in their Lives: St. Anthony the Great, while observing the rule of the Ninth Hour (corresponding to three o’clock in the afternoon), was granted a Divine revelation; and when St. Sergius of Radonezh was reciting the Akathist to the Mother of God he beheld the Blessed Virgin accompanied by the Apostles Sts. Peter and John.

My beloved brother! Do submit your freedom to the rule: having deprived you of ruinous freedom it will bind you only to the extent that it will give you spiritual freedom—freedom in Christ. At the beginning the chains may appear heavy, but later on they will become precious for the one who wears them. All saints of God took on and bore the good burden of the rule of prayer; and so you too should follow in their footsteps and thus follow the example of our Lord Jesus Christ Who, having become man, and having set us the example of how to behave, acted the way His Father did (Jn. 5:19), and said what His Father commanded Him to say (Jn. 12:49), being determined to do the will of the Father in all (Jn. 5:30). The will of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit is one. With respect to men it consists in their salvation.

O All-Holy Trinity, our God! Glory to Thee! Amen.

Bishop Ignaty Brianchaninov, translated from Sochineniya (Works), Vol. 2, Ascetic Exercises, St. Petersburg, 1865, pp. 181-191; in the Journal of the Moscow Patriarchate 6 (1986)