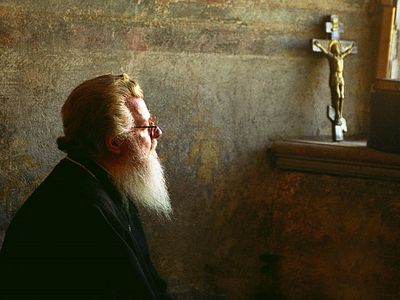

In 1998, my family and I were received into the Orthodox Church. I had served as an Episcopal clergyman for 18 years prior to that. I left a large parish with a wonderful staff and tremendous programs. I took up the work of starting an Orthodox mission. Of course, such a life-change creates awkward moments for your friends, colleagues, and former parishioners. What do you say to someone who just chucked a career to start a mission in a warehouse? Perhaps the common expression, typically American, was, “I’m glad you’re doing what makes you happy.” It would have also been beyond awkward had I responded by telling the truth: “Actually, it makes me miserable.” And the difference between their thoughts and mine, their actions and mine, is all the difference in the world. It was a difference that was at the heart of my conversion and it separates Orthodoxy from the modern world.

The Scottish philosopher, Alasdair MacIntyre, dates the collapse of modern moral thought to the rise of choice and the decline of character as the basis of virtue. Without becoming too academic in that analysis, we can simply say that modern people tend to honor choice above everything else, and have almost no understanding of character. And, not strangely, they consistently use their freedom to choose people of bad character to govern them. They look for leaders whose rhetoric most closely resembles their own choices, not understanding that the world is formed within the depths of our being, in the molding and shaping of a virtuous soul. They do not understand that their ill-driven choices may actually be bad for them. Stated boldly, it is possible to say that modern people have become the kind of persons upon whom freedom is wasted.

And thus, the banal responses to my conversion. “Happy” is one of the acceptable choices in our society. “Successful” is another one. “Following your passion” has become the new catch-phrase for “happy.” To say to someone that you willingly and freely chose a path that you thought would be hard, possibly disastrous, and that made you miserable sounds like insanity to the modern mind. Why would anyone do such a thing?

My answer is that you do such a thing if you believe it is the truth and that choosing such a path sets your feet on the road to salvation. You do such a thing if you believe that other paths are the way of destruction and that, no matter how much pleasure they might bring, they are to be abandoned sooner rather than later.

Character is the word that answers the question, “What kind of person are you?” It is a good predictor of the things you might choose, indeed, it is almost the only reliable predictor of human behavior. The word “character” comes from the Greek (surprise) and means the image left behind in wax after the seal has been pressed on it. It is something that is formed and shaped. Virtue is a name given in classical thought to the habits of character that have been well-formed in a great soul. Bad character describes someone whose character has been shaped by passions and the vices.

You can trust a person with bad character – to act in his own self-interest. And if his character is truly bad, then you can trust that what he perceives as “self-interest” is relatively short-term and pleasure-centered. But you should not trust him with your money or your wife, much less your children.

Modern culture, as MacIntyre and others have observed, has abandoned the notion of virtue and replaced it with a false anthropology of freedom and choice. Such an anthropology of freedom and choice is false, because it fails to ask the simple question, “What kind of person is doing the choosing?”

This is the failure of modern democracies. Freedom and democracy alone guarantee nothing. The prior question must be, “What kind of people are doing the voting?” To be a Jew in a room full of Nazis who are free to choose is not good news. America’s founding fathers were closer to classical Christian civilization than we are. A number of them knew that democracy was never any safer than the character of the people it served. If the people become vicious (governed by vice), then the Republic will become a vicious state. However, their experiment in creating a new civilization failed to institutionalize the making of virtue. In time, the laissez faire approach to character has proven itself to be a failure.

The same approach has come to be adopted within modern Christianity. Faith is now seen as a choice to believe, made by free persons. The assumption is that, given sufficient and accurate information, people will choose well and rightly. A primary sacrament of this flawed theology is adult-only baptism. Infants are not able to choose and are therefore disqualified from Baptism. The presumption is that somehow, a person will become an adult and freely choose to follow the right way. No other civilization in history has made such a foolish gamble with their children.

Character and virtue are formed over years through various “practices.” Practices are a set of actions and behaviors and relationships engaged in for a common good. They are by nature not simply ideas to be studied, but things that must be done. The goods of a practice “can only be achieved by subordinating ourselves within the practice in our relationship to other practitioners” (AV191). This is a philosophical way of saying that character and virtue are acquired through apprenticeship. We learn them and acquire them in the same manner we would learn a trade.

Of course, a practice requires some knowledge of the good it wishes to acquire. And this is the role of tradition. Tradition is the living memory of the good that is to be desired. It is the memory of what it means to be a virtuous person.

All of this sounds like something out of a fantasy novel. Who in your life has taken you on as an apprentice in order to teach you virtue? And what kind of “practices” do you engage in within your life?

There are many practices. If you are in a profession, then you acquired it as a practice. But it may be in deep disarray in that its “good” is either not known, ill-defined, or rarely mentioned. Teaching is such a thing. But many teachers and the systems in which they work today no longer understand the nature of the good. What constitutes a well-taught high school graduate? Etc.

Sports and the military are two of the practices within our culture that still work. The military still knows how to train an effective killer (among other things). And sports know a great deal about what kind of character is required to win. Of course, both of the goods envisioned by those practices may not necessarily embody virtue.

The Christian life, as lived in the Church, is a practice or a collection of practices. The Church is, properly, a school of virtue. The practices that its people engage in should be productive of virtue. The Church should ask us not “what do you want to be when you grow up?” but “what kind of person do you want to be when you grow up?” And then set about forming and shaping that person (the character of Christ) within us.

Practices require a narrative, a story that makes sense of their actions. The gospel of Christ is written in the practices of the Church.

“…you are an epistle of Christ, ministered by us, written not with ink but by the Spirit of the living God, not on tablets of stone but on tablets of flesh, that is, of the heart. (2Co 3:3)

When the gospel becomes an expression of personal desire and happiness, it has been hijacked by a foreign narrative. What do the pleasures of this world have to do with the Cross of Christ? Christ did not die for our self-fulfillment.

The gospel of Jesus Christ “is to die for.” Speaking to a group of Anglicans not long before my conversion, I was asked questions about the decision I had made and announced. Some were concerned for my “well-being.” The conversation turned around the question of “being happy.” Finally, I said to them, “You should live your life in such a way, that if the gospel of Jesus Christ were not true, then your life would make no sense.” I told them I felt deeply blessed that such an occasion and path had presented itself to me.

What epistle is being written in your heart? What does the world read there?