...not seeking mine own profit but the profit of many, that they may be saved (I Cor. 10:33)

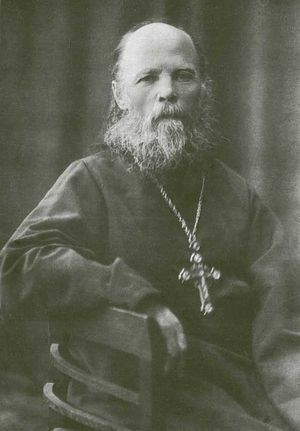

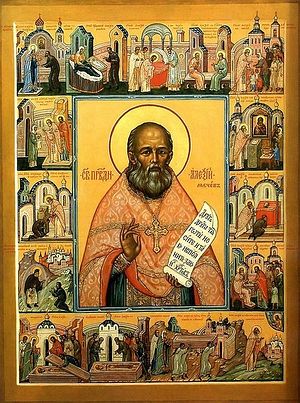

These words were spoken at the funeral of Archpriest Alexey Mechev who, in the years proceeding his death in 1923, was popularly esteemed among Moscow' s outstanding pastors. He was a rare example of a married priest endowed with clairvoyance, a gift which enabled him to heal countless battered souls, in the tradition of the great Optina elders whose spiritual offspring he was. And like St. John of Kronstadt, another of his mentors, this skilled physician operated in the midst of a great metropolis with all the complexities that this brings to life.

Although no formal biography exists, memoirs left by his spiritual children reveal a wealth of pastoral experience and counsel which can be effectively applied even now to souls oppressed by the multiple distractions and demands of today's world.

"Live for others"

Fr. Alexey was born in 1860, the son of a choir director in the service of the great Metropolitan Philaret of Moscow (+1867). The family lived in modest circumstances. "I never had a room of my own," Fr. Alexey recalled. "All my life I've lived with people around!" Judging from the only extant letter to his wife Anna, he was happily married; they had several children before her tragically premature death. None of the children appear to have remained close to their father with the exception of a son Sergius who succeeded Fr. Alexey as priest at St. Nicholas' church on Maroseyka street, before joining the ranks of Russia's New Martyrs in 1941.

Fr. Alexey's success did not blossom overnight. Describing the early years of his pastorate he said:

"For eight years I served the Liturgy daily in an empty church. One archpriest said to me: 'No matter when I pass by your church, the bells are always ringing. Once I went in--nobody. Nothing will come of it. You're ringing in vain." But Fr. Alexey steadfastly continued serving--and the people began to come, many people. He would tell this story when asked how to establish a parish. The answer was always the same: "Pray."

"In his domestic life," writes one of his spiritual children, "Batiushka was extremely simple and humble. In his study, in his little room, there were piles of books--some lying open, letters, lots of prosphora on the table, a folded epitrachelion lying together with a cross and Gospel, and little icons. The general chaos indicated that Batiushka was always busy, that he never had spare time, that there was always waiting for him--at home, on the street, in church--some great task calling for his love and self-sacrifice."

"Live for others, and you yourself will be saved." This was Fr. Alexey's motto. "To be with people," he would say, "to live their life, rejoice in their joys, sorrow over their misfortunes ... herein lies the meaning and way of life for a Christian, and especially for a pastor."

Fr. Alexey's own life was consumed in the service of others, The same spiritual son writes: "Outside his apartment the line of laboring and heavy-laden stood from early morning. And Batiushka managed to have a talk with each of them, to caress, to console ..." "Never, it seems," recalls another, "was he ever alone. He was always with people, and in sight of people; it was as though the walls of his room were glass -everything was visible ... He told me two or three times toward the end that he'd like to be off by himself, that people were getting the best of him. But that was just two or three times--no more. “Let' s all go to a monastery!” he'd say half in jest. 'You, me--all of us together!'"

Many people, particularly intellectuals, had difficulty understanding and accepting Fr. Alexey's approach because, quite simply, they didn't understand the essence of Christianity. This is well illustrated by the case of Vladimir S.:

Knowledge puffeth up, but charity edifieth

"I became acquainted with Batiushka soon after the February Revolution of 1917. I remember that when I first went to the church on Maroseyka, there was a lot there that bothered me. It was, in fact, a real conflict between the mind and the heart, between adherence to the law on the one hand, and a profound love--covering and fulfilling the law--on the other hand ... I was bothered because my love for God was weak, because I saw religion simply as a path towards satisfying a thirsty and curious intellect. I liked the strict, well-ordered and harmonious system of dogmas, I delighted in the beauty and universal conformity of the ecclesiastical rites. I believed in God, I was devoted to the Church, but I had little love for the Lord. And this cold, rational attitude towards religion subsequently ruined me, and even led me to leave Batiushka ...

The church on Maroseyka street

The church on Maroseyka street

"When I came to Maroseyka ... I saw the following: a priest of small stature, with a lined face and tangled beard, was serving together with an old deacon. The priest wore a faded, violet kamilavka; he served somehow hurriedly and, it seemed, carelessly: he was forever coming out of the altar to give confession at the cliros; sometimes he talked or searched for someone with his eyes; he himself carried out and distributed the prosphora.

"All this--and especially the confession during Liturgy--had an irritating effect on me. And the fact that a woman read the Epistle, and that there were too many communicants, and the uncalled-for Blessing of the Water [after Liturgy] ... None of this agreed with my conviction that conformity in church rites was absolutely essential. /.../

"[But gradually] I became involuntarily attached to Maroseyka; I became accustomed to the church services, and their deviations from the Typicon no longer bothered me. On the contrary, nowhere could I pray so fervently as at Maroseyka. Here one sensed that the walls were permeated by prayer, one sensed a contagious prayerful atmosphere which one didn't find in other churches. Some people, whether by tradition or out of desire to hear a deacon and choir, go to wealthy and renowned churches; here people came for one reason alone--to pray ...

"It happened that one would come to Father Alexey with some complex dogmatic problem. He would say with a smile: 'Why are you asking me; I'm an ignoramus' ... 'You're forever wanting to live through your mind; you should try to live as I do--through the heart.' This 'life through the heart' explained many of the deviations in church service which Batiushka permitted. When reason said that it was necessary to observe the prescriptions of the Typicon--not to confess during Liturgy, not to take out prosphora after the Cherubic Hymn, not to communicate late-comers at the north door after Liturgy, etc., etc.--Batiushka's heart, burning and overflowing with love, caused him to disregard reason.

'How can I possibly refuse someone confession,' he would say. 'Perhaps this confession is the person's last hope, perhaps by turning him away I may cause the ruin of his soul. Christ didn't refuse anyone. He said to everyone: "Come unto Me ..." You say, What about the law? But where there is no love, the law does not work unto salvation; true love, however, is the fulfillment of the law (Rom. 13:8-10).'"

Vladimir's comments may leave the impression that Fr. Alexey didn't particularly care or wasn't well-versed in the Church service rules. This isn't true:

"A first-rate expert on the Typicon and the services, he noticed everything, saw everything, all the mistakes and omissions in the service, especially with those young people with whom he served in his latter years (and he loved serving with them). But he left the impression that he saw nothing, noticed nothing. After some time had passed, at a convenient and appropriate moment, he'd bring up the matter and correct it. The more glaring errors--or the ones which had some bearing on the service--he'd correct himself in a manner so discreet that it passed unnoticed by the server who had erred, much less by the congregation: he himself would start to sing in the proper manner, or would do something that someone else was supposed to have done. This is a very rare quality among the clergy."

Fr. Alexey often said that "each person has his own particular path to salvation. One mustn't set a common path for everyone; one mustn't try to workout a formula for salvation which would apply to all people. People are born with different natures, different abilities, intellects and constitutions--so, too, they each go towards Christ at their own pace, each on his own path. Because of this, Christianity considers equally soul-saving the chaste monastic life and marital life, the priesthood and laity, the rank of soldier and the rank of judge--as long as Christ dwells in the heart ... And the task of an elder or a spiritual father is to uncover a person's calling and to point out to him the path which he should take towards the Lord."

With his gift of clairvoyance, Fr. Alexey had no need to speak to his "patients" in order to diagnose their maladies. And his "treatments" showed this masterful physician to be a man "not of words, but of spirit, of power:"

"It seemed that Batiushka didn't really say much; from his face alone, his smile, his eyes, there streamed such gentleness, such understanding, that this in itself comforted and encouraged a person without any words ... He actually, as he himself put it, 'unloaded' people's sins; he transformed people from despairing, oppressed pessimists into Christians constantly rejoicing in the Lord. One had only to glance at his commemoration book, checkered with hundreds of names of both living and dead, a book he always had with him, and one understood the words which he spoke, pointing to his heart: 'I carry you all here.’”

The scope of Fr. Alexey’s pastoral influence may be judged by the tens of thousands who gathered for his funeral. The liturgy was served by Bishop Theodore Pozdeyev (later, archbishop and New Martyr), attended by 80 clergymen--hierarchs, priests and deacons. The imprisoned Patriarch Tikhon, freed for a few hours, met the cortege at the St. Lazarus cemetery, where he served a lity for the deceased. Altogether, it was a fitting tribute to this remarkable pastor who had been, for so many, a stepping-stone to God.

(Quotations translated from Otets Aleksei Mechev; YMCA Press, Paris, 1970)