Twelve Vital Questions, Part I:

Archimandrite Tikhon at the Moscow Theological Academy

Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov)

Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov)

The topic you’ve set, “Restoring the spiritual tradition of Orthodox monasticism in our Church today,” is undoubtedly of the greatest importance for our Church. I’m firmly convinced that neither the Church in nor any Local Church can exist all its fullness without monasticism.

Several years ago I had occasion to be in France. Some very pious and sincere people (including several archpriests) asserted that France needed to have its own independent Local Orthodox Church. I dared remark that at the present time this is absolutely unfeasible if only because in France, with all due respect to the four or five small monasteries there, Orthodox monasticism is almost completely non-existent. When this institution – which is, without any exaggeration, the salt of the local Christian community – will flourish, then one can begin to discuss the creation of a Local Church there.

I began with this example in order to indicate immediately my position concerning the importance of monasticism within the Church. It’s probably unnecessary to expand on this topic at length before this audience.

We’ll conduct our meeting as follows: here I have twelve questions. I’m happy to reply to them, as well as to reply to questions from the audience.

1.

“Uphold the typikon, and in time the typikon will uphold you”

Question: The significance and meaning of the typikon [ustav] in monastery life. Organizing the backbone of the parish community.

Recently an approximate—I emphasize, approximate—monastery typikon was proposed to the Commission on Monasticism as part of the Inter—Council Presence of the Russian Orthodox Church. How much discussion this has provoked! Anyone who has followed it can confirm this.

The typikon is exceptionally important. One of the Holy Fathers said something to this effect: Uphold the typikon, and in time the typikon will uphold you and your monastic community.

Head of the Moscow Sretensky Stavropegal Monastery, His Holiness Patriarch Kirill, and the brothers. Photo: G. Balayants/Pravoslavie.ru

Head of the Moscow Sretensky Stavropegal Monastery, His Holiness Patriarch Kirill, and the brothers. Photo: G. Balayants/Pravoslavie.ru

My generation, to put it in secular terms, was lucky. Or, to put it in our ecclesial terms, God’s great mercy befell us: we—priests, monks, and bishops—were vouchsafed to revive dioceses, monasteries, and churches. We’re fortunate people. You’ll no longer be able to experience that which was experienced by those who were called to serve the Church in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

I know remarkable bishops who revived one or two dioceses, and some who even revived three. Can you imagine what that involves? Who else in the history of the Church has experienced anything like this?

When the bishop in Yakutia, Vladyka Herman, arrived on the vast territory of his diocese there wasn’t a single church left. Twenty years later, when he left by obedience to another diocese, he left dozens of parishes behind him. And how many abbots and abbesses have come to abandoned places and revived the monastic life!

I told this story once before when I was asked about my attitude towards today’s monasteries, and I will repeat it again: when we were novices at the Pskov—Caves Monastery, none of us ever recognized these renewed monasteries and we sometimes even made fun of them. How could it have been otherwise? We were living side—by—side with great Elders, and here Optina and Valaam were being reopened… There were words for them in currency: “Young Communist camps” and the like.

I very much regret this stupid, childish irony.

There are probably many young men and women in their twenties, or around that age, who are sitting here. Back then it was people your age, who knew next to nothing about the Church, who came to these ruined monasteries. Many came to places where the abbots themselves were not very experienced and the spiritual fathers were not such as one might have desired.

True, a certain percentage of these young monks returned to the world… But still, a significant number remained! And they have withstood this unseen warfare for twenty or more years. Now take a look at them today: what amazing, wonderful, wise, humble monks and nuns they are!

All sorts of things went on. There were revolts in monasteries. There were growing pains. But have a look at Optina, Valaam, Solovki, and other monasteries—there are remarkable people, ascetics, praying and struggling in the majority of them, having been forged by these very, very difficult yet simultaneously happy years.

This, you know, is a very interesting topic for research: the period of the last twenty years in our Church. There are many topics here for reflection and study, including the revival of monasteries. How was a monastic community created? How did all this come about? What mistakes were made? What advances have been achieved that we today could recommend and discuss both on a church—wide and, so to speak, a monastery—wide level? This is all extremely interesting and important.

As far as your question regarding the monastery typikon is concerned, I shall not attempt to generalize about the experience of others, but will rather discuss in detail what I myself know: the practice of our monastery.

I hadn’t known any other monastery apart from the Pskov—Caves Monastery. Therefore I transferred its typikon, as best I could, to our Sretensky Monastery.

With time, after fourteen years, we created a group for preparing our own typikon—this was before the church—wide discussion—and submitted its proposal to the final decision of the brotherhood. We hold spiritual councils of the brotherhood, in which novices are also included: we have them undergo a fairly lengthy training period—and even before this they live in the monastery for several years while studying in our seminary.

Compared to other typikons, ours might have its peculiarities—but one needs to remember that a typikon always depends on a monastery’s location and obediences.

For example, we serve Midnight Office a bit later than usual—at quarter after six—in order to make it somehow possible for our parishioners to make it to the monastery in time for Liturgy. Besides the monastic community, we also have a parish—moreover, one of the largest in Moscow. Our hieromonks have the obedience of being spiritual fathers. This is perfectly natural for a monastery located in a city.

Fifteen hundred people, if not more, come to church for the early and late Liturgies on Sundays. It’s for these parishioners that we monks are now building a new church: there hasn’t been enough room in the old one for some time and often people are forced to stand outside.

Although Sretensky Monastery is located in the center of town, there are few residential houses around us; people come to our services from all over Moscow, and from as far away as the suburbs. We are very happy about this, of course, but at the same time it’s also an enormous responsibility.

Our typikon also has such peculiarities as nighttime services. They began on New Year’s during the first year of Sretensky’s existence, nearly twenty years ago. Those were the first brothers, who were altogether different, and I was no prize myself.

Then, towards the end of December, I faced a question that became more and more pressing: how to meet the New Year?

Photo: Anton Pospelov/Pravoslavie.ru

Photo: Anton Pospelov/Pravoslavie.ru

When we announced that we would be serving a Liturgy on New Year’s night, we thought that none of our parishioners would come—or maybe ten or so. But, to our astonishment, at midnight the church was full. The next year even more people came.

After a few years of this practice, I was summoned to the Patriarchate and asked: what are you doing there? I said: we do such—and—such, pray fervently to St. Boniface, and celebrate New Year’s. No one is forced to be there. Everything is supervised.

And, you know, this tradition has taken hold. We were followed first by one Moscow church, then by another, then by a third—and now the Liturgy is served on New Year’s night in a great many churches. This is the case throughout the country as well as in the Russian diaspora: in ROCOR (The Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia) they’ve begun serving the Liturgy on the night of December 31 to January 1.

That’s how we began serving at night. At first we did so rarely: for example, our very first year we established another tradition of serving the Liturgy on the night of the murder of the Royal Martyrs.

Now we serve at night at least three times a week, sometimes four. Those of you who will become abbots in large cities will understand the importance of this: priests are very often busy hearing Confessions during the Liturgy, but one also wants to serve, and at night this becomes possible.

According to our monastery’s typikon, the brethren receive Holy Communion frequently, for which reason we sometimes hold two services a night. All of our hieromonks are happy to serve at night. Our students also love to come: they sing on the kliros and up to thirty of them receive Holy Communion. Naturally, nighttime services do not free them from morning classes.

We try not to invite parishioners to our nighttime services: we ask them to give us the chance to pray in peace. People today are mighty strugglers: plenty of them are happy to stand through church three nights in a row! As on Saturdays and pre-festal days, we again have to hear Confessions until twelve o’clock at night—and then there’s still the entire Liturgy to come. Therefore we earnestly ask, and even beg, our parishioners not to attend these services. Most of them respect this, although some say: “No, we want to struggle alongside you!” And one cannot just kick them out…

We do not perform molebens (supplicatory services), leaving that to our brethren among the married clergy, since there are plenty of churches nearby. We serve panikhidas (memorial services) only on Saturdays. We don’t do “services of need”[1] apart from travelling to take Holy Communion to the sick. This is proper for a monastery.

A second peculiarity of our typikon is that our brethren receive Holy Communion, on average, three or four times a week. This is the rule of St. Basil the Great. We arrived at this practice gradually, not all at once.

We all have quite a few obediences: every priest and deacon has several of them. But as important as these obediences are, one cannot allow them imperceptibly to become the one thing needful, overshadowing what’s most important.

Thus, in addressing the habitual monastery dilemma between obedience and the spiritual life (although obedience is also part of the spiritual life, but that is the topic for another conversation), we arrived at the conclusion, which we felt with all our souls, that continual Communion of the Holy Mysteries is essential given our life circumstances. Later we remembered the rule of St. Basil the Great and consulted Fr. John (Krestiankin). He blessed this liturgical life, although not immediately, and in time it has taken root.

So now, I repeat, our priests, deacons, monks, and many novices—with the blessing of their spiritual father—receive Holy Communion three or four times a week. And some priests, who have a special blessing, do so daily.

Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov). Photo: V. Korniushin/Pravoslavie.ru

Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov). Photo: V. Korniushin/Pravoslavie.ru

I know that this position has many critics, and I understand their arguments perfectly well. I accept their point of view, all the more so because many of these critics are my friends. But in our monks we see the extraordinarily beneficial fruits of our practice—and it’s not only our practice—of many years.

I’m not saying that we should introduce this in all monasteries. But I can assert that this liturgical practice has upheld us in many ways. This is the typikon we adopted, and that now helps us.

In the Sretensky Monastery we have another important event: the brotherhood’s service. Once a week on Thursday, on the day we commemorate the Mystical Supper, we all receive Holy Communion at the Liturgy. We also introduced these services gradually, but quickly came to understand that this was the right decision. A Liturgy at which the brethren receive Holy Communion together unites and focuses them in Christ like nothing else—it’s incomparable.

The brotherhood has general Confession once weekly, as in all monasteries. It’s mandatory that priests say Confession, even if briefly, every time before they serve or receive Holy Communion, even if these are daily services.

We have a clause in our typikon regulating use of the Internet. Regardless of the fact that many of us have obediences connected with the Internet—either with the website or with publishing—it is strictly forbidden in cells as a cruel devourer of time.

Absence from the monastery is a fundamental point. This can occur only with the blessing of the abbot or his assistant. During these past almost twenty years there hasn’t been a single case when I’ve not given my blessing to someone. But the rule itself is strictly observed and, if I see that someone is neglecting it, I express my most profound bewilderment.

We’ve recently witnessed active criticism of the Inter—Council Presence’s document containing an approximate monastery typikon. I take such criticism very calmly, even though I am, if not the project’s author, then in any case a member of the Inter—Council Presence’s Commission on Monasteries.

I’d like, first of all, to remind you that it’s an approximate typikon that’s been offered for discussion. What does this mean? Following approval by the Council of Bishops, this approximate typikon would be passed on to, say, Sretensky Monastery, where we would discuss it with the brotherhood. We would adapt it to our monastery and supplement it in such a way that it would be proper and useful to our circumstances.

Then we would return it to the bishop, because nothing can be done in the Church without the bishop. We would receive his blessing. Or perhaps the bishop would change or correct something.

That’s probably everything with regards to the typikon. Let’s move on to the next question.

2.

“The most important thing in parish life is the selflessness of the priest, the spiritual father”

Question: Organizing the backbone of the parish community. How should parish life be arranged?

To be honest, I must admit that we did not arrange parish life in any special way whatsoever. Everything came together by itself, through life and spiritual necessity.

The most important thing in parish life, as I see it, is that there be sincere believers in Christ and selfless care by the priest, the spiritual father for his flock. Then both the backbone and the community will be in place.

There is the spiritual father, who prays with his flock, receives Holy Communion with them from the one Chalice of Christ, meets the spiritual needs of his parishioners, and leads them to Christ. Then there are the parishioners, who trust their priest as the pastor placed there by God’s Church. That’s everything; nothing more is needed.

Youth ministry, prison ministry, charitable work and so forth should be an integral part of this central activity—but, of course, one doesn’t need to introduce all these various activities into a parish mechanically, especially if it’s numerically small.

For example, I’m afraid to visit prisons. Never in my life will I go there unless I’m compelled. I’m afraid of those places. But we have someone in our monastery, Hieromonk Luke, who just sits and waits to go. By all means! We send him there regularly and he very happily—and, it must be said, with benefit to the inmates—spends time there. But were someone to order me—“Fr. Tikhon, take up prison ministry!”—I would say: “Can’t I take up something else instead?” It’s unlikely that anything that’s forced will work out. But, on the other hand, if a priest tries to justify his indifference and idleness by saying that he’s incapable of doing anything, then this is a grave sin before God. Be sincere, desire with your whole soul to serve the Church, and the Lord will send you work to do in His House.

In the monastery now we have many priests, glory be to God, which makes things easier in this sense. Someone works with the youth—and it’s clear that he has a talent for this, and that it’s working out. Someone else takes care of charity work. We began holding talks with young people at one point, some seventeen years ago, not because we had been sent orders from above, but simply because it had become necessary, the need had somehow made itself felt.

3.

“For a monastery, I consider it to be correct and useful—and, dare I say, spiritually useful—when the monks largely or wholly support their monastery financially”

Question: The Patristic approach to the material support of monasteries or parishes. Can there be any means other than donations?

Yes, there can be. I think that if a priest can earn money for a church or monastery, and there’s no wherewithal for church needs, then not only can he earn money for it, to the extent that he’s able, but he should. But this is my own purely personal opinion. There is also a fundamentally opposed position: that a priest should not, and therefore cannot, become involved with everyday concerns.

Here another question comes up: just how sad are the well—known and endless pains that parish rectors and other priests must go through to ferret out funds for their churches! Don’t these count as everyday concerns? Or do they perhaps count as hesychia or noetic activity?

I can reply to your question based on my own personal experience. When I was appointed superior of the metochion of the Pskov Caves Monastery, the very first question that Fr. John asked me was: “Do you have a piggy bank?” I was dumbfounded. “A piggy bank!” Batiushka repeated. I marveled: “A piggy bank in what sense?” “Money for repairs, renovation, construction, the choir, staff salaries, cleaners, for support of the brotherhood, for dishes, for electricity, for water, for heat…” I grew dejected: “No.” “Well then, you need one. Take care of it.”

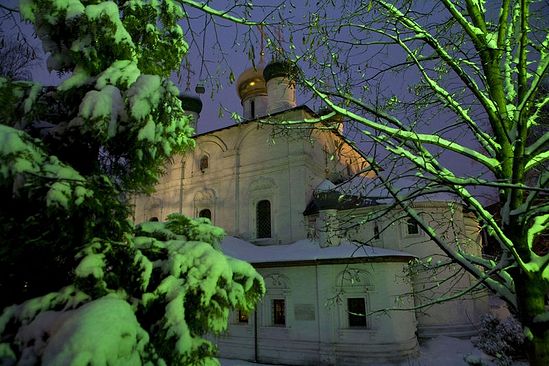

Festive lights on Christmas, Sretensky Monastery. Photo: Anton Pospelov.

Festive lights on Christmas, Sretensky Monastery. Photo: Anton Pospelov.

But the monastery itself was simply in ruins. Huge amounts of money were required for everything. In time three paths emerged: either beg with cap in hand, or earn the money ourselves, or pray that everything would just fall from heaven and people would just come, as in the life of St. Sergius: “Look, a cart filled with alms!” But I couldn’t say, “Now I’m just going to pray, and everything will be bestowed upon us.” We followed the first, second, and third paths. There were benefactors, glory be to God. There was also the fact that we always put our trust in God. But the entire brotherhood also worked hard by earning money (I beg your pardon) for the monastery. After all, offerings by parishioners weren’t enough to cover even the upkeep of our single church.

We immediately started up a publishing house and began releasing books, which were so essential for the Church then. I remember it was 1994. First we took out a bank loan, with interest of course. Then we published three or four books and repaid the loan. Then we had the necessary means for providing for the church and monastery, to renovate the buildings. And off we went. Now we publish quite a few books, and this has become our primary financial resource.

As far as monastery life is concerned, during the past five years we’ve been wholly self—supporting. Before this, we earned about 85% of our means and received about 15% through donations. Now we take care of all our financial matters ourselves, glory be to God.

But as far as the construction of the new church is concerned, here of course we are getting help from our friends, for which the brotherhood, the parishioners, and I are deeply grateful: we wouldn’t be able to manage such a large construction by ourselves.

For the life of the monastic community, for the annual repairs of the church and the buildings, for the utilities, for the upkeep of the brotherhood, for staff salaries (a seminary with 200 students, a publishing house, several internet sites, an agricultural cooperative, an orphanage, and so on—altogether there are about 500 employees)—by God’s mercy, so far we are self—supporting. It’s only been in the past year that my friends have helped us with the upkeep of the seminary, while for the previous thirteen years we had gotten by on our own.

But in a parish everything is rather different. Under normal circumstances, a parish priest won’t have to worry too much about earnings; he needs first of all to pray, to minister to the people, and everything necessary will come around. There’s enough for everything: for the upkeep of the church, for repairs, and for salaries.

But to raise a large church or monastery from nothing—that is on another order of magnitude altogether. When Vladyka Longin, the Metropolitan of Saratov, was given the ruined metochion of the Trinity—Sergius Lavra twenty years ago, he also opened a publishing house as well as a sewing workshop, making the fabric himself, since he also needed to earn money. But for him prayer and monastic activity on the one hand, and care for the wellbeing of the monastery, the support of the brotherhood, and earning money on the other hand didn’t in any way conflict with each other. They added up to a single spiritual obedience in establishing the monastery.

After all, it’s only from a liberal perspective that St. Nilus of Sora and St. Joseph of Volokolamsk can be seen as being opposed to each another. There wasn’t any kind of irreconcilable conflict between them—that’s all fiction. St. Joseph has a wonderful saying that we’d all do well to remember: “The day is for labor; the night is for prayer.” Metropolitan Pitirim (Nechaev), who considered himself a disciple of St. Joseph, loved to repeat this. St. Joseph had a truly prayerful, ascetic monastery; the monks themselves were complete non-possessors. It’s another thing that they had to feed many thousands of deprived people during the famine, as well as to care for the education and enlightenment of young Christians who would go on to become priests and bishops of the Holy Church.

Solovki Monastery was also fully self-supporting, as was Valaam.

Therefore, for a monastery I consider it to be correct and useful—and, dare I say, spiritually useful—when the monks largely or wholly support their monastery financially.

4.

“The celebration of the Divine Liturgy is the cornerstone ”

Question: Organizing the spiritual life in a parish or monastery. Key points.

Photo: V. Korniushin/Pravoslavie.ru

Photo: V. Korniushin/Pravoslavie.ru

It’s very important for a monastery to serve the Divine Liturgy daily. For a parish, perhaps several times a week. The Liturgy is the cornerstone of the spiritual life of both the community and the priest.

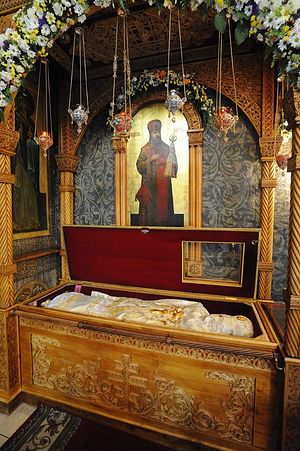

Second, sacred shrines. There should be a sacred shrine around which the monastery is united. I exerted a great deal of effort in having the relics of the Hieromartyr Hilarion brought to us. This was also a whole chapter in the life of our monastery. We need special spiritual protection. This might be an especially venerated icons or holy relics, but there needs to be some kind of sacred shrine that will play a very important role in the life of a church or monastic community—our special hope, a saint or the Mother of God, sent to us by the Lord to strengthen and uphold us.

I’d like to mention a few more key points. One needs to be careful about not tonsuring people into monasticism too quickly. Fr. John warned me about this as well. I haven’t always heeded his warning, and have later regretted it. But, in general, our novices undergo a fairly lengthy trial period. Over the course of twenty years, three of our tonsured monks have returned to the world. For us, this is quite a few. Sometimes people say to me: in such-and-such a monastery practically everyone left, in another one ninety percent of the original group left… But I let this go in one ear and out the other. For us, these three are very many.

St. Ambrose of Optina said: “So as not to be mistaken, you should not hasten!” This is very, very important.

What else can be said about key points of the spiritual life?

Of course, there needs to be a spiritual father. I absolutely don’t consider myself to be any kind of spiritual father, but this is what Fr. John blessed: for me to be both abbot and spiritual father, and I have continued to carry out this obedience for twenty years.

Confession for the entire brotherhood every week is absolutely essential. It’s very important to teach all the priests to have Confession, whenever possible, before every service. Even if one receives Holy Communion three or four times a week, one should have Confession each time. It’s good if this becomes a necessity. Let liberal theologians laugh at this and harp on about how Confession needs to be separated from Communion!

Of course, a feasible prayer rule. We have a common, monastic prayer rule. Of course, there is reading and being immersed the Gospels. By the way, we’ve just published a special Gospel with the Savior’s words in red. From my own modest experience, I know how important it is to read the Savior’s words conscientiously. One begins to perceive the Word of God in a completely different manner than previously, with freshness and extreme clarity. This doesn’t at all mean that one always needs to read it this way. But, from time to time, this helps like nothing else to perceive with new force those words that we know so well and have read so many times.

Meeting with the brotherhood, discussing spiritual matters of vital concern, replying to questions—this is also a periodic necessity.

There’s still another extremely important and constructive spiritual activity: attentively reading the Holy Fathers, and love for such reading. And, of course, the Jesus Prayer.

Theological education. After the monastery had been open for about three years and we already had twenty or twenty-five brethren, I sent them out to study, initially through the Moscow Theological Seminary’s correspondence courses. But I very quickly realized that this was insufficient. They studied poorly and were forced to go out of the monastery.

Later we started the Sretensky Theological Seminary. At first this wasn’t easy, but later everything came together with God’s help. All of our brethren, with the exception of maybe one or two, have gone through seminary.

Common pilgrimage. Every year we go on pilgrimage with the brotherhood. This has already become a tradition, although I don’t know how long it will continue. We’ve gone to Jerusalem, to Kiev, and various holy places around Russia. After Pascha we leave a few priests on site and go on a common pilgrimage for four or five days. For priests it is important that they see life in other monasteries and churches with their own eyes.