Churches were burning in Pakistan, while African Christians died and radical forms of Islam threatened monasteries, sanctuaries and villages in Egypt, Syria and Iraq.

That was 1997. Human-rights scholar Paul Marshall kept hearing one question over and over when he addressed this rising tide of persecution: Why didn't more American Christians protest as their sisters and brothers in the faith were jailed, raped, tortured and killed?

Some Christians, he said, were distracted by apocalyptic talk in which persecution was a good thing, a sign that the end of the world was near. Others weren't that interested in violence on the other side of the world that threatened believers in ancient churches that looked nothing like their own suburban megachurches.

"The result is a stunning passivity that calmly accepts such suffering," said Marshall, in an interview for an earlier column for Scripps Howard News Service. "Perhaps this ... could be justified if we were dealing with our own suffering. But to do this with the suffering of another amounts to theological sadism."

That was 1997. Marshall had just co-written the groundbreaking book "Their Blood Cries Out," with journalist Lela Gilbert. Since then, I have worked with both of these writers in global projects about religion-news coverage.

Now it's 2013 and the news about the persecution of Christians has only gotten worse. Marshall, Gilbert and Catholic lawyer Nina Shea recently completed a new volume titled "Persecuted: The Global Assault on Christians."

The bottom line: This topic is more relevant than ever.

A year ago, German Chancellor Angela Merkel said, "Christianity is the most persecuted religion in the world." While some mocked her words, a Pew Research Center study in 2011 found that Christians were harassed, to one degree of violence or another, in 130 countries — more than any other world religion. British historian Tom Holland told a recent London gathering that the world is witnessing the "effective extinction of Christianity from its birthplace" in the Middle East.

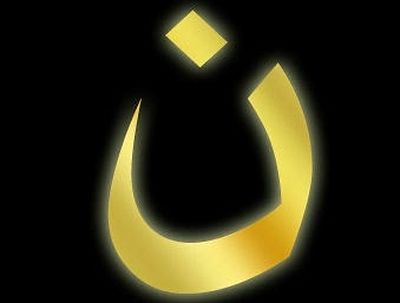

Recent losses endured in Egypt have been staggering, with more than 100 Christian sites attacked by well-organized mobs in mid-August, including the destruction of 42 churches — the worst assault on the Coptic Orthodox Church in 700 years. In Syria, rebels linked to al-Qaida overran Maaloula — famous for being one of three remaining villages in which locals speak ancient Aramaic, the language of Jesus — damaging the priceless St. Thekla monastery and trashing two churches.

Then the headlines got worse, with Islamist gunmen killing 67 or more people in the Westgate mall in Nairobi, Kenya. While Muslims were freed, hostages who would not recite the Shahada — an Islamic confession of faith — were tortured and killed, before their bodies were mutilated. Days later, the Taliban claimed credit for an attack by two suicide bombers on the historic All Saints Church in Peshawar, Pakistan, in which at least 85 worshippers died.

Pope Francis addressed these issues during remarks on Sept. 25, noted John L. Allen Jr. of the National Catholic Reporter when reached by email. He is the author of a new book titled "The Global War on Christians: Dispatches from the Front Lines of Anti-Christian Persecution."

In Allen's translation of the event, the pope asked the crowd: "When I think or hear it said that many Christians are persecuted and give their lives for their faith, does this touch my heart or does it not reach me? Am I open to that brother or that sister in my family who's giving his or her life for Jesus Christ? ... How many of you pray for Christians who are persecuted? How many? ...

"It's important to look beyond one's own fence, to feel oneself part of the Church, of one family of God!"

While the truth is painful, Marshall said in a recent interview, it's important to asking questions about all those silent believers and their silent churches. If anything, it appears that many American Christians are even less interested in global persecution trends than they were in the past, while their churches are even more independent and focused on a therapeutic, individualistic approach to faith.

"It's like all of these horrible events are just blips on the screen. They are there, then they are gone and forgotten," said Marshall. "Sometimes, it's easy to think that Christians in America don't even know what is happening to their brothers and sisters around the world."