SOURCE:

The Michigan Daily

By Peter Shahin

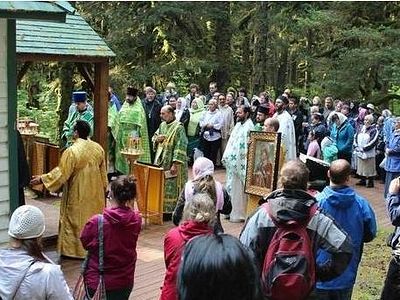

He was neither. For generations, his family had been Greek Orthodox Christian, stuck in the middle between a wealthy and influential Maronite majority and a Druze and Muslim minority backed by the Ottoman government.

It’s hard to know exactly what his village was like when he left. Today, Khiam Marjayoun — the same village journalist Anthony Shadid’s parents came from — is one of the few Orthodox Christian outposts left in Southern Lebanon, a stony town on a rolling green Lebanese hill.

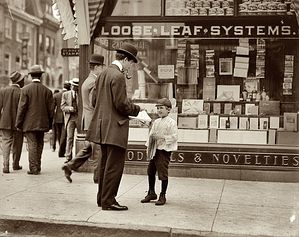

His father was blind and his mother was handicapped — though his father made a meager living by being the village herbalist. (I once referred to the job as a “witch-doctor,” which earned the justified wrath of my grandmother.) As the Ottoman Empire waned, my great-grandfather left Lebanon, alone, at about 16-years-old — hoping to avoid the Ottoman draft and find work in America.

The country that adopted him sent him to war in 1917 — where he fought in the fields of France for a nation that was barely his, for a people he hardly knew. His first view of Old Europe was probably in a dirty trench with wet socks, where he inhaled mustard gas and resolved to only donate to the Salvation Army — since they gave soldiers free coffee while the Red Cross charged for it.

When he returned from the war, he found the successful chain of grocery stores he had built in Flint, Michigan had disappeared — as had the money — with a relative who had been charged with keeping the business while he was away. So, like millions of men from his generation, he became an autoworker. For decades, he worked in the manufacturing complex that would become the famed “Buick City,” perhaps now more remembered for being progressively demolished from 2002 to 2006 than for the millions of cars that rolled off its assembly lines over the half century it existed.

Though the manufacturing job went well, the mustard gas from the fields of France continued to haunt him every winter — when he would contract pneumonia — but he had to go to work or not get paid. In the summers, he saw men in the steel casting plant, collapsing from heat stroke, being physically dragged away by managers and replaced with new workers to keep the line rolling.

He again found himself at the edge of history when he participated in the formative 1937 Sit-Down Strike, protesting those horrendous conditions. My grandmother said, “He wasn’t anything special. He was just one of the workers.” But I still think that’s something. The strike led to the recognition of the United Automobile Workers by General Motors and later Chrysler and Ford.

After that, his life seemed mostly uneventful. He raised my grandmother and her siblings, helped build a church for Arab Orthodox Christians in Flint and died while drawing a GM pension.

I never knew him. Sorry for the letdown. He died in the 1970s, well before I was born. But his life does serve as an inspiration for my own — and perhaps the legend is greater than the man himself.

I’m the child of two teachers, both born and raised in Midwestern America. Three generations hence, my family is still Greek Orthodox, though I don’t identify with being an Arab-American like any of the generations that preceded me. I’m more than happy with the food, but I don’t feel the need to debate or dwell on absolutist political positions in Middle East policy or smoke a water-pipe — sorry, now called a “hookah.”

As I’m trying to find my way in this world, I find myself drawn to my own family’s history for inspiration. I don’t need to leave my country with nothing to my name to start over in a foreign land — thank God for that. But I do think America offered something different to my great-grandfather than it does for me.While studying abroad in Russia last year, my professor said he was one of those people who thrived on discomfort — the kind you get from being a stranger in a foreign land. I would like to think I’m one of those people too. My great-grandfather must have been. Instead of traveling abroad and returning home, he made a new home, where every day was a challenge to build a life and family while trying to respect his cultural inheritance but assimilate to his new country.

Something my great-grandfather did out of necessity, I hope to do by choice. He left his country to find new opportunities in another country; I hope to leave mine to represent it abroad. My goal is to be a Foreign Service Officer — a diplomat representing the United States. For my great-grandfather, life in the United States meant economic security, freedom and safety from the sectarian clashes of the old world. For me, the modern American life makes it difficult to build something enduring while racing from job-to-job and city-to-city searching for that elusive promise of economic security.

The two pictures that I’ve seen of my great-grandfather are of an austere, well-mustachioed young man about my age and another from the late 1950s, as a wrinkly, smiling and proudly toothless old man bouncing my father on his lap. At the very least, it’s comforting to know that the life of an immigrant-soldier-autoworker can lead to happiness — which, when I’m feeling cynical, I think is restricted to those getting the $75,000 “starting street” salary in their first year out of the Business School.

I’ve never been to Lebanon. The country of my ancestors (for full disclosure, half of them) is still wracked by violence and plagued by a weak government. A century after my great-grandfather left Lebanon, the Maronites and Muslims have flipped demographics, but it’s still a very divided country with an unfortunate penchant for never-ending retaliatory rocket attacks. Eventually, maybe, I’ll get there. For now, it seems about as distant as America must have seemed to my great-grandfather.