Pravoslavie.ru has been running a series dedicated to the twentieth anniversary of the restoration of monastic life in Sretensky Monastery, featuring monks who live there. One of the most recent talks was with Hieromonk Pavel (Shcherbachev), the deputy secretary of the Patriarchal Council for Culture, which is run from within the monastery walls.

***

Hieromonk Pavel (Shcherbachev). Photo: A. Pospelov/Pravoslavie.ru

Hieromonk Pavel (Shcherbachev). Photo: A. Pospelov/Pravoslavie.ru

—The Patriarchal Council for Culture was formed in March of 2010 by resolution of the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church. The head of the Council is His Holiness Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia, and the Secretary is the abbot of Sretensky Monastery, Archimandrite Tikhon (Shevkunov). Included under the auspices of the Patriarchal Council for Culture, in accordance with resolution concerning its formation, are matters of dialogue and working cooperation between the Russian Orthodox Church and its departments, and the state cultural institutions, creative unions, and community citizens’ associations working in the sphere of culture, as well as athletic and other similar organizations in the countries of the Moscow Patriarchate’s canonical territory.

Culture today is a multifaceted thing, containing a multitude of inner contradictions, interpretations, and, as you will, worldviews. Nevertheless, this is one of the platforms upon which the Church can conduct constructive dialogue with creative people about beauty, which, in the words of Feodor Dostoevsky, will save the world, about ethical values of modern man, about the preservation of our great Christian cultural inheritance, and about the divine soul as a source of true inspiration and authentic talent.

The cooperation between the Church and cultural society is grace-filled ground for preaching the Gospel among people who are searching for truth in art. Many of them are tormented by the question of the meaning of existence; they are trying to fathom the mystery of creativity hidden deep within the human soul. They may at times get lost in the process, straying into what the apostle calls philosophy and vain deceit, after the tradition of men, after the rudiments of the world, and not after Christ (Col. 2:8).

They are often lacking someone close by who could show these wanderers in the fog—at times, unfortunately, a substance-induced fog—the path to God, Who is the Giver of gifts of grace, of all wisdom, and blessedness. This guide may not even be a priest—who is appointed by God to perform this service—but any Christian who is ready to provide an answer with meekness and a blessing to someone needing it.

—What projects is the Council working on today?

The activities of the Patriarchal Council for Culture are quite diverse. Folders for correspondence, plans, creative projects, analytical notes, reports, and proposals now contain over a hundred thousand pages. One of the most important tasks placed before the Council is to preserve those precious objects of our cultural inheritance, which over the recent decades have been returned by the State to the Russian Orthodox Church. To this aim, at the blessing of His Holiness Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia, in the near future a position will be instituted in many dioceses of the Russian Orthodox Church, with the responsibility of preserving and restoring the invaluable heritage handed down to us by our pious ancestors. The resolution concerning this diocesan “guardian of antiquities” was prepared by the Patriarchal Council of Culture. To prepare those appointed this position, the Council will coordinate with the Ministry of Culture to organize courses, in which Russian national specialists in museum work will read a cycle of lectures, with field trips for the practical study of historical objects.

The Patriarchal Council for Culture also developed a special committee for cooperation between the Russian Orthodox Church and museum societies. The commission, together with the commission from the Ministry of Culture, resolves issues of contention over the use of monuments of spiritual culture under the auspices of State and Church, in an atmosphere of mutual understanding and good-natured cooperation.

The monument to Holy Hieromartyr Hermogenes. Photo: A. Pospelov

The monument to Holy Hieromartyr Hermogenes. Photo: A. Pospelov

This is but a small portion of what the Patriarchal Council for Culture does. It would take an entire large volume to enumerate all the projects. Nevertheless, some of the more significant activities of this Synodal department are such multi-dimensional projects as: participation in the work of the Council for Culture and Art of the President of the Russian Federation; erecting a monument to Holy Hieromartyr Hermogenes in the Alexander Garden in Moscow [outside the Kremlin]; publishing grants for the preservation of monuments of Church architecture and art; participating in the creation of textbooks on Russian history; organizing the exhibition “Orthodox Rus’. The Romanovs”, which took place in the Moscow “Manezh” from November 4–24, 2013; creating a project for conducting exhibitions, in cooperation with the State Historical Museum, dedicated to St. Sergius of Radonezh; renewing ancient Christian churches and monasteries in the northern Caucasus; conducting the “Days of Russian Spiritual Culture” in the U.S. and China; participation in preparations for the Olympics in Sochi; and many, many others.

At the “Romanov” exhibition. Photo: I Pravdoliubov/Pravoslavie.ru

At the “Romanov” exhibition. Photo: I Pravdoliubov/Pravoslavie.ru

—You were involved in the re-opening of the Monastery of St. Joseph of Volokolamsk. Tell us about these events.

—The Monastery of St. Joseph of Volokolamsk was returned to the Church 25 years ago. At the time, I was assistant to Metropolitan Pitirim of Volokolamsk and Yuriev, and worked directly on the documentation for the return of this ancient monastery. All efforts to resolve this issue through correspondence with state institutions brought no results. After so many years of persecution against the Church, the state bureaucrats were not able to overcome a certain invisible psychological barrier. This was not fear, but most likely an administrative reflex. The situation was resolved in an unexpected manner: Having met Mikhail Gorbachev while attending a high-level conference, Vladyka Pitirim brought up the subject of the bureaucratic red tape he was encountering while trying to return the St. Joseph Monastery to the Russian Orthodox Church. Gorbachev related to this sympathetically, and soon drafted a resolution containing only three words: help the Metropolitan. In one week, the Ministry of Justice gave a report on returning the Monastery of St. Joseph of Volokolamsk.

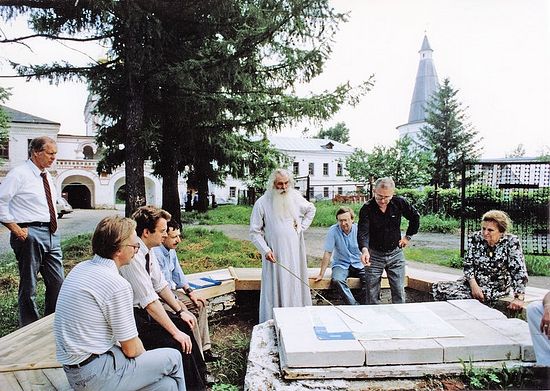

Discussing the plans for the restoration of the Monastery of St. Joseph of Volokolamsk. Early 1990s.

Discussing the plans for the restoration of the Monastery of St. Joseph of Volokolamsk. Early 1990s.

—You knew Metropolitan Pitirim well. What sort of monk was he?

—Metropolitan Pitirim was an outstanding archpastor. Over the course of more than thirty years, he headed the Publishing department of the Moscow Patriarchate. Printing religious books was very complicated under the conditions of the current state politics, which were aimed at quelling everything connected with Church enlightenment. Nevertheless, he not only published books and built a new, modern building for the Publishing Department, he also educated many young Christians, and helped them received theological educations. Many of these would later become outstanding hierarchs, priests, and religious workers.

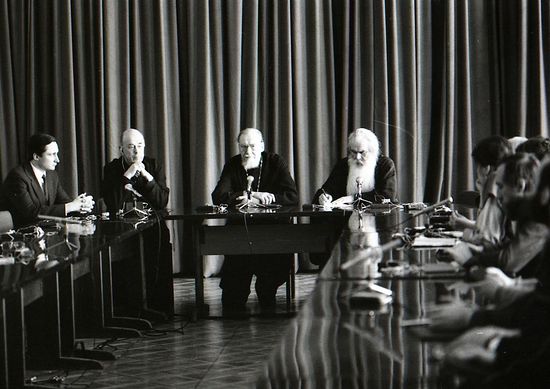

At a meeting presided over by Vladyka Pitirim. At left: Mikhail Shcherbachev. Photo: M. Yurchenko/Pravoslavie.ru

At a meeting presided over by Vladyka Pitirim. At left: Mikhail Shcherbachev. Photo: M. Yurchenko/Pravoslavie.ru

Vladyka Pitirim knew many monks who went through the terrible school of Soviet prisons and concentration camps. His spiritual guide was an Optina elder who is numbered among the holy confessors, Schema-Archimandrite Sebastian of Karaganda. One can certainly learn about monasticism from such people. They witnessed to Christ in more than word—they witnessed by their lives. Although burdened with many labors, Vladyka never neglected his monastic prayer rule, and in critical situations he was an example of deep humility and hope in the all-powerful Providence of God. At the same time, he remained a very simple and accessible person.

I am made all things to all men, that I might by all means save some (1 Cor. 9:22). I think that this is how the ancient, experienced monks, through their own lives, taught a very complicated work—the art of sacrificing yourself in your service to God and people.

—I would like to ask you one popular question that probably everyone likes to ask monks. Why do people join monasteries? Couldn’t they be more useful to society if they were to remain in the world, applying their talents there?

—The fact of the matter is, the question is framed somewhat inappropriately. The life of a Christian living in a monastery does not differ essentially from the life of a Christian living in the world, with a family, if the latter leads his life according to the commandments of Christ. The monastery is no more than a kind of hothouse, where fragrant and beautiful plants can be grown that will bring forth good fruit in their time. This fruit is valuable, and capable of filling many of those who hunger for spiritual food. The Church is founded on monasticism. Monasteries, which have existed in Russia and in the entire Eastern Orthodox Church from ancient times, were always centers of theology, missionary work, enlightenment, social service, and even assiduous management.

—How does the obedience of a clergyman in a city monastery differ from that of some other place?

—It city monasteries, as a rule, there is a significant number of parishioners and pilgrims. All different kinds of people come. In order to spiritually guide such a flock, the priest must, in any case, understand their inner world: not only their problems, experiences, and spiritual searches, but also the basic factors influencing these people’s souls. This means that the pastor is obligated, besides praying and continually teaching the word of God, to have a good knowledge of the realities of life surrounding us. Without this knowledge it will be hard for him to understand his rational sheep, and thus help them in the work of the salvation of their souls.

At a meeting dedicated to the ten-year anniversary of the repose of Metropolitan Pitirim (Nechayev) of Volokolamsk and Yuriev. Photo: A. Pospelov/Pravoslavie.ru

At a meeting dedicated to the ten-year anniversary of the repose of Metropolitan Pitirim (Nechayev) of Volokolamsk and Yuriev. Photo: A. Pospelov/Pravoslavie.ru

I think that for priests in rural areas it is more characteristic for them to be occupied with building and caretaking of the property. Living in a village, these matters are unavoidable. Beyond this, the rural pastor, as a rule, has more time for prayer and reading, for spiritual self-improvement.

—What place does pastoral work occupy in your monastic life? You have to spend a lot of time talking with people, or hearing their confessions. Many come with all different problems and illnesses. Where do you get the strength for this?

—The priesthood is a precious gift of God, which leads a man into very close communion with his Creator. In fact, there is probably no greater joy on earth, no greater happiness or blessedness than the gift of communion with God. This gift is capable of transforming a corruptible man into a god by grace. The bitterness comes in recognizing your sinfulness and imperfection, the falling short of your spiritual state in comparison with the exalted Christian ideal. You are only left to hope in God’s mercy. But God abundantly gives the strength for service to the Church. One must only have the resolve. But this can be difficult.

As for confession, this obedience is for me, personally, a joyful one—especially when those who approach this sacrament of repentance sincerely and deeply repent. This joy, in the words of the Savior, is in the presence of the angels of God over one sinner that repenteth (Lk. 15:10).

Hieromonk Pavel (Shcherbachev) James Billington of the Library of Congress, and Nun Cornelia (Rees) in Sretensky Monastery, 2012. Photo: A. Pospelov/Pravoslavie.ru

Hieromonk Pavel (Shcherbachev) James Billington of the Library of Congress, and Nun Cornelia (Rees) in Sretensky Monastery, 2012. Photo: A. Pospelov/Pravoslavie.ru

—Probably you are often asked why grief, suffering, and death exist in the world…

—Human life is a veil of tears. You could say that in the life of any person, there are more afflictions, sicknesses, everyday hardships, and emotional sorrows than there are exaltations and those beautiful moments, which, contrary to the famous, lofty expression, cannot be stopped. In Christianity, our earthly life is called “carrying our cross.” Every person has his own life’s cross. The most important matter is whether or not that person is willing to bear it. If a person who has been visited by hardships or illnesses falls into depression, starts grumbling, and gets angry or sad, he will find himself in a spiritual dead end. But if he arms himself with another frame of mind, another way of thinking, and says, “I thank You, O Lord, for these sorrows, for these troubles, and sicknesses that You have willed to send me. For my sins, I deserve worse,” then the sorrows, sicknesses and troubles that earlier seemed unbearable immediately become easier to bear, and soon they disappear altogether like a morning fog. This is the work of a humble condition of the soul.

There is also another side of the matter. Ancient ascetics have said that hardships catch up to a person who tries to run away from them; but if he bravely meets them head on, hardships get scared and run away. The holy fathers also had the following thought: “Where it’s hard, that’s for us; but where it’s easy, we should think hard about it and be cautious.”

At the grave of Met. Pitirim (Nechayev)

At the grave of Met. Pitirim (Nechayev)

Our earthly life is a kind of test. If a person does not want to correct himself, then the merciful Lord in His love for mankind sends him trials. These trials lead a person to think about how he needs to reassess something in his life—to put in it modern language, he needs to reboot his system. Of course, this is easy to describe in words, but in everybody’s experience, when the Lord visits us with sorrows and sicknesses, a broad field for spiritual labor opens up.