To be frank, when I read that letter I was dumfounded: There in black and white was written that over 200 writers from all over the world call upon the Russian government to repeal the laws prohibiting homosexual propaganda and insulting religious sensibilities.

But I was even more shocked to learn that among these writers were twenty-seven Nobel Laureates.

How about that!

That means that the entire world of writers is “in step” (including certain Russian writers who also signed this letter) and we Russians—including other writers—who support these laws are hopelessly backward and can’t possibly understand what it means to be free people, and what freedom of expression means.

When I began to ponder it, I looked at the names of the Nobel Laureates among the signatures, and the writers’ position became a littler clearer to me, because I recalled a few of their works. Then I remembered the position of the Nobel committee that grants the prizes, especially within recent years—their position is not just strange, but in fact surprising to the reading public. But when I recalled Saltikov-Schedrin's words: “The government should always keep the public in a state of surprise,” I was a little comforted because I could relate our great satirist’s words to today’s Nobel committee.

But last night I was tossing and turning. I couldn’t sleep.

And I recalled the little girl, Matryosha, from Feodor Dostoevsky’s novel, Demons,i and the chapter entitled “At Tikhon’s”, which was withheld from publication for nearly a hundred years.

Here I have to explain everything connected with this chapter of this great novel—what I remembered last night, and what I wrote down this morning after checking the details.

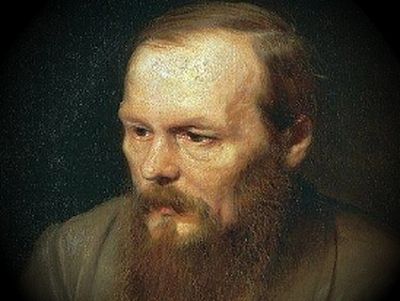

I learned about Matryosha as an adult, when in a serious volume entitled “Literary Heritage” (Gorky Institute of Literature) I read for the first time the published chapter, “At Tikhon’s” from the novel Demons by Feoder Mikhailovich Dostoevsky.

In 1872, in the journal Russky Vestnik, where the novel was published, the editor of the journal Mikhail Nikiforovich Katkov decidedly insisted that this chapter be stricken from the text of the novel. The argument of this authoritative critic and polemicist was so categorical that even Dostoevsky, also a brilliant polemicist, had to give in.

What else could he do?

Katkov told the writer that everything in this chapter was immoral, that despicable acts were described in it, and they should not be shown to God’s world under any circumstances—regardless of the protagonist’s own confession that he acted like a cad.

Nearly a hundred years go by, and the chapter about the girl Matryosha has finally appeared to readers—and at that only to those who study the works of this great Russian writer.

At the time, in the 1970s, I decided to write a short story about the last days of Feodor Dostoevsky’s life. This was because I had learned an amazing detail of the writer’s life and death. On the night of January 26, 1881 when he began coughing blood, in the neighboring apartment, just beyond the wall of the office where Dostoevsky used to work at night, a certain Alexander Barannikov, one of the leaders of “Narodnaya Volya” (the people’s will)—the organization that prepared the assassination attempt on Emperor Alexander II—was ambushed and arrested. Feodor Mikhailovich could not help but hear how they “took” Barannikov and his friends—at night, all sounds are a hundred times louder. This means that he coughed up blood not so much because he was reaching under his cabinet to pick up his pen, as his wife Anna Grigorievna wrote in her Memoirs, but more likely because he knew that dashing revolutionary whom he had probably run across many times on his staircase, or in the yard near his building. It is amazing that the Ober-Procurator of the Holy Synod Constantine Petrovich Pobedonostsev, whose life was dedicated to struggling with just such people as Barannikov, would also have seen the latter in the stairwell on his way up to Dostoevsky’s apartment.

Having studied the details surrounding this fact little known even to professors of literature, a fact that sheds so much light upon the life of this beloved writer, into whose apartment a terrible truth was bursting, I learned that Barannikov was young, handsome, and smart—just like Stavrogin from the novel Demons!

Well, I read in another volume of the fundamental Literary Heritage, which was written mainly for specialists in the field of literature, the chapter, “At Tikhon’s”—the very chapter cut out by Katkov, which is essentially the corner stone that explains the plan behind the novel Demons, and the main character description of the novel’s central figure—Stavrogin.

My impression of what I had read was such that I was stunned, and felt as if I had just been in the room where the terrible event had taken place. It was as if I had seen with my own eyes how girl of twelve or fourteen came to meet a man with the surname Stavrogin, endowed not only with a remarkably handsome physical appearance and strength, but also with a mind and talent, having at the same time just as impressive vices. Before this she lay on her bed in a fever, thin, with pink spots on her cheeks, her nose sharpened, and melting away like a thin church candle.

So she rose from her bed, walked over to the open door in the room her torturer was renting, watching for several days now how his victim was dying.

“She watched me silently. During these four or five days, during which I had not since that time once seen her up close, she had truly wasted away. Her face had as if withered, and probably her head was hot. Her eyes had become large and they gazed at me unmoving, with some dull curiosity, as it seemed to me at first. I sat in the corner of the sofa, looked at her, and did not move. Suddenly I felt hatred again. But I very soon realized that she was not at all afraid of me, but was perhaps more likely in a state of delirium. But she wasn’t in delirium, either. She suddenly started shaking her head rapidly at me, as they do when making some strong reproach, then suddenly raised her little fist at me and began threatening me with it. In the first moment this movement seemed comical to me, but as it went on I could not bear it—I rose and moved toward her. There was such despair in her face, a despair that is impossible to behold on the face of a child. She kept shaking her little fist at me threateningly, nodding her head, reproaching.”

This is what was written as if not by Dostoevsky, but by Nikolai Stavrogin, on the pages of his confession that he brought to the elder, Tikhon. Dostoevsky used this device of “alienation” to provide an opportunity to speak from the character himself, and not from the writer, so that the reader himself would be present at the described event.

In any case, that is what happened with me.

I saw how, just for fun or for some other feeling, when “everything is allowed to a person if there is no God,” Stavrogin entered the room where Matryosha was alone. How he approached her, started fawning on her as if playing, overcame the girl’s fright, and corrupted her.

After the event Stavrogin experienced a real fear, knowing that labor camp awaits him if Matryosha tells anyone what happened. But she doesn’t; she gets sick, and wastes away in a fever. And here Stavrogin is saved just in time by the arrival of his lover’s governess. He is having an affair with the governess, too. And although he is indifferent to her, she is after all “not bad”, and therefore Nicholai Vsevolodovich closes the door and immediately forgets his fear and Matryosha.

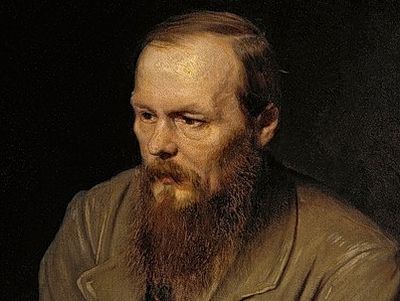

The many researchers of Dostoevsky’s works all unanimously write of his amazing ability to penetrate the psychology of his heroes, allowing him to create profound and complex characters in the people who inhabit his works. Many write, especially in recent times, about his prophecies—especially when speaking about the novel, Demons.

Yes, this is really true: the creation of a “group of five” shown in Demons, the senseless and cruel murders, the blood of which binds these members of the “underground”, foretold a half a century previous to the actual results declared by the “strugglers for the people’s happiness”. “A hundred million heads” that they are not sorry to take off and even consider necessary for the sake of a “bright future”, as the character Shigalev declares in the novel, really were taken after October 1917.

And the “demons” such as Petrusha Verkhovensky, capable of stirring up not only a provincial town, as shown in the novel, but even whole countries, also exist, are also real, and Dostoevsky predicted their appearance with astonishing accuracy.

But from the time of Mikhail Nikiforovich Katkov to the present day, there have been oblique references to the novel’s main protagonist’s main crime—precisely what Stavrogin wrote in his “pages”, which he brought to elder Tikhon.

Meanwhile, this is the main chapter, the foundation upon which the great novel was written.

What did Dostoevsky want to show by making this protagonist a man whose beautiful facial features suddenly turn into a mask, and his noble impulses into crimes? Perhaps one of satan’s brood has appeared before the reader?

Feodor Mikhailovich’s contemporaries pronounced a monstrous sentence against him: The author has gone out of his mind, entered the madhouse and has not left it. He has dreamt up personalities that do not exist. He is finished as a writer; it’s the end of him.

Our contemporaries write about Demons as an ingenious, prophetic novel. In the complete collected works, the chapter “At Tikhon’s” has finally been published.

But the same silence is still kept about the writer’s Orthodoxy, his fervent faith, which helped him to throw himself fearlessly into the terrible abyss. He could throw himself in and not be harmed, walking away the winner, both when he wrote the novel and now, when everyone can read the chapter “At Tikhon’s", and see the thin, little fist, with which the dying girl Matryosha threatens her killer.

Yes, only a genius, only an Orthodox Christian could write such a chapter. Feodor Dostoevsky was just such a genius.

But what crimes and human deformities do today’s Nobel Laureates, these “signatories” who call us to repeal the “draconian” laws we have passed within the recent year and a half, write about?

Take Elfrida Jelinek, for example—the Austrian novelist, playwright, poet, and literary critic. The more often read and screened of her novels are The Piano Teacher and Women as Lovers. The main heroine of The Pianist is endowed with every conceivable and inconceivable sexual perversity that the writer probably knows from her “sexual enlightenment”, so widely inculcated in the prosperous European countries from the time of infancy.

But at the same time, the heroine is an exquisite expert of music, and teaches at the conservatory. That is, the author is showing us that vice is inseparable from talent—music, in this case. The perversities are not just named, given “indirectly” as with Dostoevsky. No, they are described in detail, accurately reproduced both in print and on the screen in the film directed by Haneke, which won him a “Golden Palm Branch” at the film festival in Cannes.

During the screening of this film in Cannes, many viewers and even critics could not stand it and ran out of the theater vomiting.

Both the novel and the film were made on a highly professional level. And the meaning of both the literature and film, lauding vice, is all the more horrible in that you can’t get away from that dark, horrible person. There is only one escape—a bullet to the forehead, as the heroine of The Piano Teacher does to herself.

I have dwelt upon this work because it graphically shows what direction literature and art are taking today in Europe and the USA; what creations are receiving the highest rewards from what used to be the most authoritative juries and committees.

Sexual perversity is being supported with everyone’s might, and moral fallenness is being purveyed as the norm, inculcated and defended by law.

The people may protest as they did in France, but the law about same-sex marriage was passed in that country regardless. That is, the most repulsive, revolting sodomy has been pronounced the norm.

“What do you want?” they try to “reason” with us. “Nature has created some personalities just like that. So, don’t prevent them from living the way they want to live.”

Yes, there are such deviations. But society has always avoided such people, even isolated them. And even they themselves hid their perversity, restrained their little passions, knowing that at least in Russia, for example, these people were from olden times contemptuously called… I won’t say the word.

Now, they are demanding “parades”. They have become the setters of fashion—that is, the norms of life.

For a long time now, Dostoevsky’s novels have become as if astonishingly relevant.

Here the youth who dreamed of becoming Rothschild turns out to be a super-modern teenager (from Youth); there another Rodion Raskolnikov turns up, thinking that killing the old lady with money is in fact quite right, because she is a “louse”, and he can and should become Napoleon.

But for some reason, no one is talking about the new Stavrogins, about those people who, simply for their own “fun” corrupt and kill children.

During recent times, and last year especially, so much has been said about the perverts who have raised their heads not only in “enlightened Europe” but also in Russia, that I involuntarily recall Stavrogin, Matryosha, and everything connected with the novel, Demons.

For Stavrogin, who started out as an inspired bearer of national, revolutionary ideas, winning over through these ideas those who followed after him (the characters stunning for their literary power—Shatov and Kirillov), gradually turns into not only an idler, wasting his life; he also jumps into reckless schemes (he has to test his strength of will!), which arouse, tickle the nerves, make you catch your breath—an “adrenaline rush” as they would say today!

And his banal dissipation leads straight to that room described in Demons, where a mother lives with her daughter, Matryosha.

We are constantly told, including by our own home-grown liberals, that man is free, that he has the right to free choice: If a man, for example, wants to live with a man, that is his right. If a woman wants to live with a woman—that’s normal. If they want to register their marriage, don’t you dare prevent them; let’s pass a law, let’s let them do what they want.

“Human rights!” They are above everything!

But that these kinds of relationships are base and criminal, don’t you dare say it—that is nothing more than your retrograde morals. The Church is on your side is simply because the Church is also retrograde, hopelessly outdated and behind modern times.

In the enlightened and prosperous Scandinavian countries, for example, many youths aged 17-18 are already experiencing sexual impotency—it’s almost becoming a pattern that they are now having to admit openly. It is because the so-called “sex education” is beginning in early childhood for them. And it turns out that the path from natural sexual relations, in which the fullness of love is expressed, to the path of perversity, to child molestation, is very short.

Today the press in the United States, and even in the entire West, published a letter from the foster daughter of the world famous producer Woody Allen. The girl openly announced that she had been subjected to sexual abuse from her foster father since childhood. The producer now lives with another foster daughter, this time having married the girl, once she came of age. The producer will soon be eighty years old.

Allen was nominated for an Oscar this year. I would not be at all surprised if the American Academy of Cinematography announces Allen the winner, and the foster daughter’s letter a falsification.

I recall this example so that we would understand who are “bringing us to reason”, teaching us “freedom”, and a “civilized” way of life.

Just the same, in my opinion, there are writers who signed the open letter not knowing who Pussy Riot, the group who performed a provocative song and dance in the Christ the Savior Cathedral, really is, and why they were punished. It is quite possible that they were bamboozled by the same avalanche of raging disinformation that appears on the pages of even respectable Western publications. But how on earth could the Nigerian writer Wole Soyinka, for example, know that the perverts who give themselves out as artists were simply blaspheming, and not “protesting” as the Western press writes? Most likely he simply read what was written in the media by those authors who stand for “freedom of expression,” and signed the letter, since they asked him to.

Well, Salmon Rushdie, the author of the novel, Satanic Verses and Nobel Laureate, knows very well what happens to people who walk into a mosque simply talking loudly or without taking off their shoes. Why then does he support these screamers who behaved so outrageously before the altar of the most important cathedral in Russia?

“Draconian” is what they call the laws passed by the Duma for the protection of religious sensibilities, aimed at those very “Stravroginian” passions.

I notice that the super-relevance of Dostoevsky’s novel Demons has turned at us an unexpected facet, which has cast a gleam like a razor’s edge.

And the question again arises mightily: Should literature and art address such an acute problem as this?

Yes, in my opinion, they should—if the writer, producer, or actor has the same power of tragic talent that Feodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky manifested to the entire world.

Yes, they should—if their faith is strong, if they firmly believe in the power and truth of Christ.

The writer’s heart was scorched for his whole life and did not break, precisely due to his Orthodox faith; because he prayed, and not only in prison, not only as a soldier.

He was brought to the faith from childhood. Yes, he forgot Christ for a period of time, but he returned unfailingly to Him.

Not everyone who loves Dostoevsky’s works knows that he was shocked by a terrible crime he witnessed at age nine. He saw with his own eyes how a girl who was raped by a scoundrel died. She was bleeding, and Feodor’s father, a doctor, was unable to saved the lacerated child. The impression of this remained on the author’s heart all his life.

Perhaps this is why he so fearlessly flung himself into describing Stavrogin’s basest fall—in order to show the entire world the thin little fist of the girl, Matryosha.

I think that only his faith helped him to bear what he described, and then the abuse and even indecent cursing he so courageously had to endure from his contemporaries, addressed at him and at his novel—as a citizen and as a writer.

During the final years of Feodor Mikhailovich’s life, he wrote in his “Notebook”:

“The scoundrels teased me for my uneducated and retrograde faith in God. These blockheads have never even dreamed about the power of denying God, placed in the Inquisitor and in the preceding chapter, and to which the entire novel serves as a reply. I don’t believe in God as a fool (fanatic). And those people wanted to teach me and laugh at my lack of mental development! Their deaf nature never even dreamed of the power of denial that I went through. Who are they to teach me!”

He is referring to his chapter on “the Grand Inquisitor” in the novel, Brothers Karamazov.

Yes, the power of his talent, of course, hung upon the power of his faith. And that is why, throughout time, throughout space, across oceans and upon mountain heights, is seen Matryosha’s little fist—in America, Europe, and Asia—in all countries, for his novels have been translated into nearly every language.

They all see the thin little fist of a child, threatening all scoundrels of the world.

Meanwhile Stavrogin, the “citizen of the Swiss canton of Uri”, hangs himself in the attic of his own mansion precisely because Matryosha’s little fist turned out to be more powerful than the seemingly invincible power of satan.