Source: Russia Beyond the Headlines

Located in the Kaluga Region just south of Moscow, Optina Pustyn is among the most venerated and beloved of Russian monasteries. Part of the appeal is its favored natural setting in a majestic pine forest overlooking the small Zhizdra River. Popular legend says that the name derives from Opta, a brigand who renounced his mayhem, accepted the monastic name of Makary and formed a forest hermitage in the late 14th century. “Pustyn" is related to the word for "wilderness" and is often used for small monastic communities in forests. In the 15th century, the retreat accepted both men and women who lived in separate areas, but were led by a common spiritual father. This practice was banned by the Russian Orthodox Church Council of 1503, and the Optina community was reconstituted for men only as the Holy Presentation Optina Pustyn Monastery. Tenuously surviving in the 16th and 17th centuries, the monastery was destitute by the early 18th century and briefly closed in the mid 1720s.

For centuries the monastery consisted of log structures. Work began in 1750 on a new main church dedicated to the Presentation of the Virgin, yet the monastery continued on the brink of destitution, exacerbated in 1764 by Catherine the Great's secularization of monastery holdings. By the end of the 18th century, however, the monastery and its attractive location gained the attention of a church hierarch, Platon, the Metropolitan of Moscow and Kaluga. His support led to a revival, including the construction in 1802-1806 of a large bell tower and flanking cloisters. Throughout the 19th century there followed other churches, chapels and monastery buildings, including a large refectory with imposing murals and ceiling paintings that have survived.

Of special significance was the monastery's hermitage, or skete (retreat), devoted to a more strict form of spiritual observance. Dedicated to John the Baptist, the skete at Optina Pustyn was established in 1821 at its own compound a short distance to the east of the main monastery walls. The center of the skete remains the Church of the Nativity John the Baptist, built in 1822. Surfaced with red plank siding, the attractive wooden structure is accented with a white neoclassical portico. Other buildings at the skete include small residences and a library housed in a graceful structure that served as a museum during the late Soviet period.

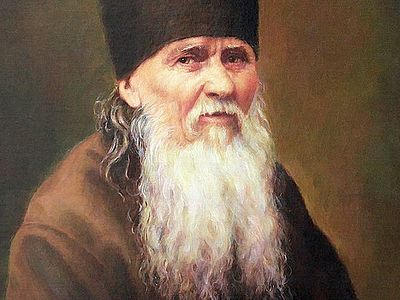

During the 19th century the hermitage became widely known for its sages who achieved the designation starets, or "elder". Although the concept of starchestvo was brought to the monastery by the church hierarchy in the 1820s, the starets designation came primarily through popular respect for certain monks who led an ascetic existence at the hermitage and in whom charisma merged with deep spiritual wisdom. The church venerates all 14 monks known as "starets" at Optina Pustyn.

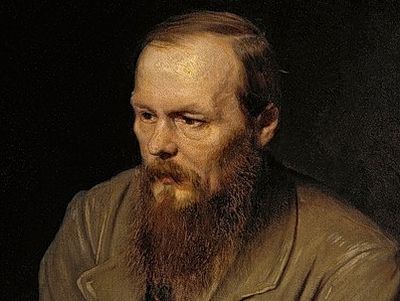

The Optina Pustyn Monastery attracted all levels of society, including Russia's intellectual and artistic elite. Nikolai Gogol, Ivan Turgenev, Pyotr Tchaikovsky, the brothers Ivan and Konstantin Aksakov, Konstantin Leontiev – these are but a few of the major artists and thinkers who visited Optina Pustyn. But the monastery is best known for its encounters with Fedor Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy – encounters that in each case involved a severe personal crisis. The events leading to Dostoevsky's visit occurred during a particularly stressful time in his life. In Spring 1878, he had begun work on The Brothers Karamazov – his final, triumphant masterpiece. In mid-May, however, his beloved younger son, Alyosha, suddenly became ill and died from a seizure at the age of two years and nine months. Seeing her husband's unfading anguish, Anna Grigorevna Dostoevskaya turned to their friend, Vladimir Solovyov, himself a profound writer and mystic philosopher. She noted that Dostoevsky had long thought of going to Optina Pustyn, and the essential moment had come. Solovyov agreed to take Dostoevsky with him to the monastery in late June.

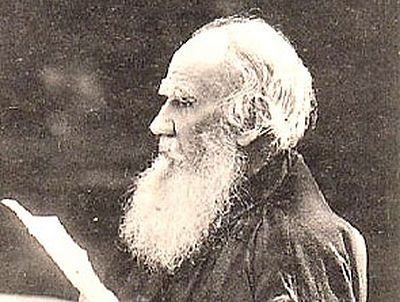

Dostoevsky hoped to arrive on June 24, which was the feastday of the Nativity of John the Baptist as well as the 40th day since the death of Alyosha. (The Orthodox church places special emphasis on remembering the deceased at that point.) They arrived, however, on the 25th, and Dostoevsky requested a memorial service (panikhida) for his son on the 26th. Dostoevsky remained at Optina Pustyn through the 27th, and during that time he sought consolation from the venerable starets Amvrosii (Ambrose), known for his compassion and penetrating intelligence. Dostoevsky subsequently conveyed these qualities in the figure of Father Zosima, the starets who appears in The Brothers Karamazov. Father Zosima's consolation of the woman who had lost her son (in the chapter "The Believing Women") likely derived from Dostoevky's encounters with starets Amvrosii – in particular, their private conversation at his modest cottage near the entrance to the skete. Anna Dostoevskaya noted that her husband returned from Optina Pustyn a different person, at peace and no longer crushed by grief. He resumed his work on The Brothers Karamazov with a new spiritual strength. Leo Tolstoy's encounters with Optina Pustyn were more frequent, but ultimately without spiritual resolution. After visits in 1877 and 1881, he returned for a meeting with starets Amvrosii in 1890, the year before Amvrosii’s death. The meeting was evidently tense and difficult for the elderly monk, who was wearied by Tolstoy's pride.

By this point Tolstoy had publicly broken with the Orthodox Church and had attacked basic tenets of Christian dogma. Nonetheless, he returned to Optina Pustyn in 1896 at the urging of his sister Maria, who in 1891 had entered the nearby Shamordino Convent. During that visit he met with starets Joseph, whose calm generosity of spirit brought a temporary measure of peace to his existence. But Tolstoy's turbulent spiritual quest would not be eased. His final existential crisis led him to flee his home in the early hours of October 28th, 1910. Accompanied by his physician, Dushan Makovitsky, Tolstoy arrived at Optina Pustyn toward the end of the day. During the difficult trip he asked frequently about the elders at Optina Pustyn. Despite his refusal to reconcile with the church, his anguish apparently led him to seek the wisdom and solace that they might provide. After spending the night at the monastery, Tolstoy approached the hermitage on the morning of the 29th. At this critical moment he was beset with doubt and the fear that he would not be received. Instead, he made his way to his sister Maria at the Shamordina Convent and even mused about staying nearby for a period of time. But the arrival of his daughter Alexandra (Sasha) on the 30th again roused him to flight. Together with Makovitsky, they made their way on the 31st to Astapovo Station, where Tolstoy died a week later. In a final turn of the tragedy, Tolstoy's retreat from the hermitage quickly became known at Optina Pustyn, which received the news with dismay. Starets Varsonofy journeyed to Astapovo but was not allowed in the presence of Tolstoy despite repeated requests. Tolstoy's closest associates had no interest in such a meeting. In the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917, Optina Pustyn was closed in January 1918. Dispersal, executions and exile ensued. During the Soviet period, most of the religious artwork was lost or destroyed. In 1931, the skete became a rest home, and the monastery housed various enterprises.

The darkest page in the monastery's history occurred in the fall of 1939, when some 5,000 captured Polish officers were sequestered there in what was called concentration camp Kozelsk-1. Walled monasteries were frequently used as prisons during this period. In 1940 this group was sent to Katyn and shot in a mass execution. Following a brief period as a military hospital, the monastery was used in 1944-1945 as an NKVD "filtration camp" for Soviet officers repatriated from German camps. In later years the territory served as an agricultural school. The Presentation Optina Pustyn Monastery was finally returned to the Orthodox Church in 1987 and services resumed in 1988. In 1990 the John the Baptist Skete was also returned to the monastery. Thus began a process of restoration whose results are so impressively visible today. Like the Solovetsky Monastery in the Russian North, which also witnessed tragic events during the Soviet era, Optina Pustyn has experienced a revival that each year attracts thousands of pilgrims and visitors.