Source: The Daily Beast

The son of an evangelical intellectual who galvanized the religious right, Frank Schaeffer has been searching for years for a coherent religious identity after fundamentalism—and he keeps getting closer.

Well-known defectors from fundamentalist Christianity—musicians, writers, preachers—sort roughly into two categories. First there are those who became agnostics, and who think Christians are misguided at best. With varying degrees of sympathy and anger, they like to rehash silly lessons from Sunday school and congratulate themselves for being skeptical. Then there are the salvagers, who sift through the Christian teachings of their youth and decide the most basic parts are worth preserving. They promote a sort of not-your-parents’ Christianity, where it’s okay to doubt God’s existence and reject the old teachings on homosexuality and gender roles.

Neither side has contributed much to the literature on religion and belief, though they have revealed a lot about the evangelical subculture. The New Agnostics seem to retain a cartoonish notion of God as a Homeric being who created the universe in a single temporal event. As for the New Christians, instead of arguing about God’s existence, they mostly try to atone for the previous generation’s mistakes by creating a more hospitable church environment with a more transparent leadership. However noble their intentions, both groups are for the most part intellectually shallow, and neither is much in conversation with spiritual traditions outside the ones they grew up in. They’re self-styled rebels who define themselves against Billy Graham’s breed of Christianity.

Then there’s Frank Schaeffer, the black sheep among purported black sheep. His father, the late Francis Schaeffer, probably did more than any other author to give the nascent religious right an intellectual backing. The older Schaeffer was a hippie-ish evangelical intellectual who moved to Switzerland and founded a haven for young philosophical seekers, and peppered his writings with honest engagement with existentialist philosophy and 70s drug culture. Later in life, he returned to the U.S. and got increasingly mixed up with conservative political causes. As Schaeffer grew more strident and political, his son was his right-hand man.

Where his peers have walked a relatively straight line away from fundamentalism, Frank Schaeffer has taken hard twists and turns since his father died in 1984: from directing slasher movies, to extolling Greek Orthodox Christianity, to writing a political column centered on denunciations of the Tea Party. Demonstrating that old fundamentalist habits die hard, he’s made each of these shifts with an almost violent conviction that he was right and most everyone else was wrong. But if this restlessness has eroded his credibility, it’s also shown him to be more intellectually curious than most other evangelical apostates.

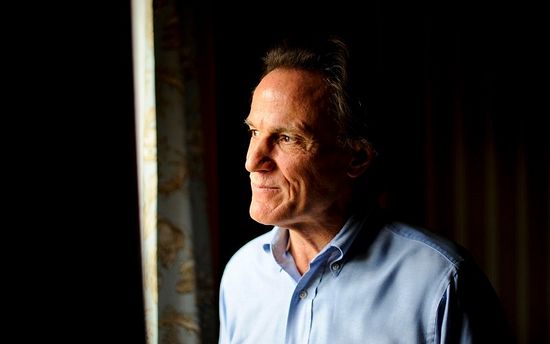

His new book, Why I Am an Atheist Who Believes in God, shows Schaeffer trying to drop this sectarianism and make peace with uncertainty. At age 62, he shows a self-awareness here that might surprise anyone who’s read his Huffington Post columns or his 1990s books on Orthodoxy; he admits he’s changed his mind many times and may change it again. It’s messy and inelegant—he self-published it, even though some of his previous titles have landed on the bestseller list—but it exhibits a wisdom rare for this milieu. At its best, the book resonates with religious traditions older and deeper than the ideas of David Hume or John Calvin, let alone Richard Dawkins: think of Taoism or Sikhism or ancient Christianity. In last year’s much-lauded book The Experience of God, the theologian David Bentley Hart wrote that real debate over belief and unbelief isn’t even possible with the two sides entrenched as they are in respective grammars of belief. Schaeffer is at least trying, if somewhat clumsily, to put them into conversation.

Schaeffer was a product of his parents’ unusual vocations. He grew up at L’Abri, the Christian commune the Schaeffers founded in southwest Switzerland. His father’s book How Should We Then Live remains the definitive Bible-thumper diagnosis of what went wrong with Western society, from the Renaissance to Roe v. Wade. To its credit, it’s widely known for convincing evangelicals it was acceptable to engage with secular philosophy and the Great Books. As Schaeffer recalls in his 2007 memoir, Crazy for God, his father took him to art museums and blasted classical music all day, and his sisters played Handel’s “Hallelujah” chorus whenever someone converted at their commune. He often listened to his father debate theology into the night with visiting college students. Later his father grew out his hair and beard and took a serious interest in Bob Dylan. His father could be temperamental and misogynistic, but the family was never plagued with major money-laundering or sex scandals.

At age 17, Schaeffer impregnated a young woman visiting the community. He married her, and while they raised their family, Frank started producing films for his father’s ministry. His disillusionment with evangelicalism occurred in the early 1980s, in the period when he and his father were riding around in Jerry Falwell’s private jet and hobnobbing with Republican politicians. His memoir recounts Billy Graham’s tips for soliciting donations: telling a rich businessman his father was fighting the socialists; talking slowly to the Southerners and avoiding the word “intellectual.” Schaeffer remembers his father squirming when Pat Robertson talked about burning a reproduction of a nude by Modigliani. Schaeffer concluded that Falwell was an “unreconstructed bigot reactionary,” Graham was a “very weird man indeed,” and Robertson “would have a hard time finding work in any job where hearing voices is not a requirement.” Schaeffer says his father ultimately agreed they were mostly “psychopaths” and “lunatics.”

After his father’s death, Schaeffer severed ties with that crowd and tried to break into Hollywood. He made several low-budget films, including the violent sci-fi movie Wired to Kill. Crazy for God describes a dark period after Schaeffer finished editing his fourth movie, when he was living in a rented room and subsisting on extra-thick pork chops he shoplifted from a grocery store. (He put them in his pants to smuggle them out even though it hurt his testicles.) Seeing street preachers and Christian TV ads made him question his career choice, but he decided nothing would be worse than returning to the evangelical world. Everything changed with the success of his first novel, Portofino, in 1992. In 1990 he also converted to Greek Orthodox Christianity. Tellingly, the book he wrote on his conversion, called Dancing Alone, was more a hostile denunciation of Protestantism than a love letter to his newfound faith.

Schaeffer heightened his hostility in 2008, when he turned against John McCain and started a liberal political column at the Huffington Post. He garnered media attention by accusing Christians who were voting against Obama of outright racism—“everything else is an excuse, just another smokescreen.” Sometimes his anger seemed to veer on pathological. In another entry he accused evangelicals of glorifying violence against children and linked to a video of a man beating his daughter. “That video of a weeping child begging for mercy is what our country will look like if the Religious right ever gets their way,” he wrote. “And if that's how they think God wants them to treat their children just imagine how gays, liberals and anyone else of the ‘Other’ will do in their theocracy.” In 2011, Schaeffer denounced several high-profile evangelical Christian leaders—particularly Rob Bell, founding pastor of the hip Mars Hill church in Michigan—for publishing their books with companies owned by Rupert Murdoch. They “worry about gay marriage between responsible loving adults,” Schaeffer wrote, “while they perform financial fellatio on the mightiest and most depraved/pagan media baron to ever walk the earth.” The column seldom mentioned his involvement with Orthodoxy, and it would be easy conclude from reading it that Schaeffer felt contempt for Christianity in any form.

But that would be mistaken, and Schaeffer clarifies some of this in his newest book. He still lives near Boston with Genie, his wife of some 45 years. He spends a great deal of time painting and playing with his two grandkids. He continues attending a Greek Orthodox church, but he’s no longer an Orthodox triumphalist; it’s simply part of his routine, and he loves the Byzantine liturgy. Likewise, he reflexively prays an old Orthodox prayer—Lord Jesus Christ, son of God, have mercy on me—throughout the day. But he vacillates between believing in a personal God and thinking theism is just an absurd fabrication: “Depending on the day you ask me, both statements seem true,” he writes in his new book. In another passage, he says he holds two ideas about God simultaneously: “He, she or it exists and he she or it doesn’t exist. I don’t seesaw between these opposites; I embrace them.” He doesn’t see this paradox as tantamount to agnosticism, but rather the truest way to describe reality—even if, as he says in another section, he has “no idea what the word true means.”

The book suffers from lack of the editing Schaeffer received at major publishing houses. His prose is choppy, and besides a general repetitiveness, the book has unhelpful excursions into subjects like The Big Lebowski and House of Cards. But it also has endearing moments. Schaeffer dwells at great length on the subjects of classical music and art, which, he says, he’s finally learned to celebrate for their own sake without marshaling them into arguments or trying to start a movement, as his father might have done.

More importantly, Schaeffer is almost onto something with his faux-agnosticism. Much of his doubt seems to be rooted in an awareness of modern scientific advancements. He believes brain chemistry undermines his sense of free will and personhood and that psychology explains away love and altruism. And as he ages, and copes with the deaths of more friends and relatives, the easy comfort he once took from believing in eternal life seems increasingly foolish. So sometimes he tries to reconcile his thoughts within an empty pantheism: “Maybe saying ‘evolution teaches’ or ‘God says’ is more or less the same thing: just another way of summing up what we know about ourselves from our collective human primate experience of what works.” But ultimately he won’t retreat from his conviction that there’s something beyond the material, beyond the scope of empirical observation. He has a sense of a “spiritual reality hovering over,” calling him to hear the voice of his creator. “It seems to me that there is an off-stage and an on-stage quality to my existence. I live on-stage, but I sense another crew working off-stage.”

This is where Schaeffer gets beyond the theological categories of evangelical Christians and their detractors. Rather than the image of God as a “cosmic craftsman,” in David Bentley Hart’s language—a God of the gaps, a supreme being among other beings, who created the universe temporally and exists alongside it—Schaeffer’s words evoke the God of various mystical traditions. As the Tao Te Ching famously declares, “The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao”—and nor is the Tao that can be marginalized by quantum physics. The Hindu chant “neti, neti”—“not this, not this”—is a way of expressing that whatever the divine might be, we limit our experience of it when we try to describe it. The medieval Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides says we can only describe what God is not: not ignorant, not impotent, not temporal. The seventh-century Christian mystic Pseudo-Dionysius goes even farther, insisting that God isn’t good, isn’t love, isn’t existent. A 17th-century Catholic priest described God as “a pure nothingness.” God is the source of being and life, and so can’t belong to the realm of being as such. The mystics say God is only knowable through experience.

Anthony Bloom, a Russian Orthodox bishop who died in 2003, gives a beautiful and profound treatment of doubt and belief in his 1971 book God and Man. Past a certain age, when critical thinking sets in, Bloom says, belief in God usually has to rest on some utterly convincing experience, an encounter that the believer interprets as God’s presence. It’s like hearing notes from a violin and knowing that it’s music rather than simply noise. Bloom says we ought to think of truth as resembling a scientific hypothesis that helps us hold together our bits of knowledge. It’s always limited and inadequate. Just as the scientist doubts his model while knowing there’s a stable reality behind it, the believer trusts that God is there, however ridiculous and anthropomorphic our notions of God might be. Theology is a deliberate falsification that points toward a deeper truth.

Schaeffer is confronting the inadequacy of the model, though he lacks the philosophical background to navigate the relationship between science and faith.

On the other hand, he has retained an attribute reminiscent of the other ex-fundies. He hardly spares any codified religion from his angry denunciations, including Orthodoxy. He mostly portrays them as retrograde and dogmatic. “Maybe we need a new category other than theism, atheism or agnosticism that takes paradox and unknowing into account,” he writes. It’s naive and arrogant to think the great spiritual traditions haven’t taken these into account for centuries. Prayer and belief don’t preclude unknowing. For all his newfound comfort with uncertainty, Schaeffer has yet to embrace the equally great virtue of solidarity. Like those other defectors, he’s still trying to blaze a new path.