We recently posted on article from Fr. John A. Peck entitled “The Four Senses of Scripture.” In this present article Fr. John Whiteford addresses specifically the sense of allegorical interpretation which is employed both in the New Testament and in Patristic Tradition, although it is often rejected by many Christians today in the various western traditions.

The rejection of allegorical interpretation as a later method is misguided, because we find allegorical biblical interpretations in the New Testament itself, and this had its roots in traditional Jewish methods of interpretation.

Philo of Alexandria (who live from approximately 25 B.C. to 50 A.D.), used allegorical interpretations of the Scripture extensively

The parables of Christ have an allegorical dimension, although Protestant scholars have generally resisted that conclusion. However, Christ Himself provided the interpretation of one parable in the Gospels—the Parable of the Sower (Mark 4:1-9)—and the interpretation He gave was clearly an allegorical interpretation (Mark 4:10-20).

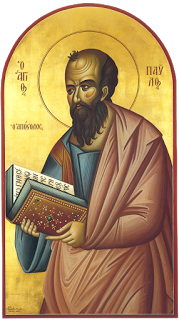

Tell me, ye that desire to be under the law, do ye not hear the law? For it is written, that Abraham had two sons, the one by a bondmaid, the other by a freewoman. But he who was of the bondwoman was born after the flesh; but he of the freewoman was by promise. Which things are an allegory: for these are the two covenants; the one from the mount Sinai, which gendereth to bondage, which is Hagar. For this Hagar is mount Sinai in Arabia, and answereth to Jerusalem which now is, and is in bondage with her children. But Jerusalem which is above is free, which is the mother of us all. For it is written, Rejoice, thou barren that bearest not; break forth and cry, thou that travailest not: for the desolate hath many more children than she which hath an husband. Now we, brethren, as Isaac was, are the children of promise. But as then he that was born after the flesh persecuted him that was born after the Spirit, even so it is now. Nevertheless what saith the scripture? Cast out the bondwoman and her son: for the son of the bondwoman shall not be heir with the son of the freewoman. So then, brethren, we are not children of the bondwoman, but of the free.

Another example is found in 1 Corinthians 9:9-10:

For it is written in the law of Moses, thou shalt not muzzle the mouth of the ox that treadeth out the corn. Doth God take care for oxen? Or saith he it altogether for our sakes? For our sakes, no doubt, this is written: that he that ploweth should plow in hope; and that he that thresheth in hope should be partaker of his hope.

Many more examples could be cited of typological interpretations of the Old Testament, found in the New.

Protestants generally wish to reject the allegorical method, but when faced with clear examples of the Apostles engaging in that very method, their response is usually to say: "Well, the Apostles were inspired to do it, but no one else is." But this is clearly an arbitrary opinion that has no basis in Scripture or Tradition.

The allegorical sense of Scripture does not negate the literal sense—it is another level of meaning in the text. Traditionally, there are four senses of Scripture:

1. Literal: This refers to the obvious meaning of the text. In some cases, the text is clearly not intended to be taken literally, but even poetic texts have an obvious meaning.

2. Typological/Allegorical: A type is a stamp which imprints an image. An antitype is that which is imaged by the type. We find the word "type" explicitly used in Romans 5:12-14:

Therefore, just as through one man sin entered the world, and death through sin, and thus death spread to all men, because all sinned— (For until the law sin was in the world, but sin is not imputed when there is no law. Nevertheless death reigned from Adam to Moses, even over those who had not sinned according to the likeness of the transgression of Adam, who is a type of Him who was to come.

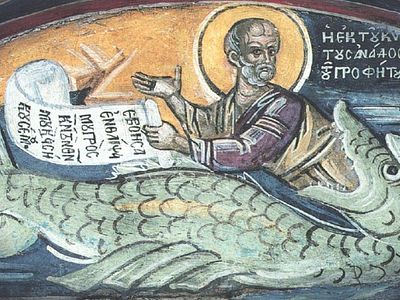

And we find the word "antitype" used explicitly in 1 Peter 3:18-22:

For Christ also suffered once for sins, the just for the unjust, that He might bring us to God, being put to death in the flesh but made alive by the Spirit, by whom also He went and preached to the spirits in prison, who formerly were disobedient, when once the Divine longsuffering waited in the days of Noah, while the ark was being prepared, in which a few, that is, eight souls, were saved through water. There is also an antitype which now saves us—baptism (not the removal of the filth of the flesh, but the answer of a good conscience toward God), through the resurrection of Jesus Christ, who has gone into heaven and is at the right hand of God, angels and authorities and powers having been made subject to Him.

A story could be composed as an allegory, such as the Parable of the Sower (The Pilgrim’s Progress being a more extended example), but an historical narrative can also be interpreted allegorically, as St. Paul did.

3. Moral: The moral sense is the practical application of Scripture on an individual or corporate level. To see this reading of Scripture in action, you can read through the Canon of St. Andrew of Crete that is prayed during Lent in the Orthodox Church.

4. Anagogical/Heavenly/Eschatological: "Anagog" comes from Greek meaning “to go up.” So this sense looks at how a passage points us to the fulfillment of all things.

Interestingly, Rabbinic Jewish interpretation of Scripture also sees Scripture as having a Four-fold sense, which has many similarities.

Protestants have reacted negatively to the allegorical method because it was used to such great excess in the west, especially during the medieval period. However, if you read the commentaries of the great Fathers of the Church, you find it used in a way that is far more balanced.

Clearly, if the Apostles could interpret the Old Testament in allegorical and typological terms, no one who claims to be a Christian should object to the Church Fathers doing likewise.