Contemporary scholars and certain Christian groups today tend to approach the study of scripture as archaeology.

Rather than receiving the scriptures as God-breathed tradition in the life of the Church, the text is abstracted from its incarnate context, subjected to scientific analysis. While much can be learned, of course, from a knowledge of Greek, Aramaic, and Hebrew, this is not an end unto itself. Popular hermeneutical methods such as the grammatical-historical are recent, being flawed in a number of ways. And really, no single approach or ‘method’ should be deemed superior to the rest.

In the end, this whole approach is undermined by a crippled foundation. The scriptures are not a treasure chest waiting to be unlocked with the right set of keys, nor are they only useful for the academic ‘elite.’

At the heart of this misguided, modern project is a desire to ‘get back to’ an ‘original’ text or meaning of scripture. But this begs the question of whether an original text–or interpretation–has ever really existed:

Scholarly interpretation has been governed by an overriding concern to establish the original text and meaning. But there are many circumstances in which this is either not appropriate or not the whole story. For the Scriptures do not simply belong to their original context: they have been read and re-read over the centuries. When we venerate the Book of the Gospels we are acknowledging it as something that belongs to the present: it bodies forth Christ now.

—Andrew Louth, Introducing Eastern Orthodox Theology, p. 9

The holy scriptures are more than just another text of antiquity; they are light and life; they are a divine witness to the true Logos of God, Jesus Christ. In the liturgical life of the Church, the Holy Spirit breathes both meaning and understanding into these words as they are proclaimed from the solea or amvon. This is what Louth calls “the liturgical use of Scripture.”[1]

The way of understanding sacred writ in the early Church and down through the centuries–many years before widespread literacy and the advent of the printing press–was in how they were utilized in our daily, weekly, and annual liturgical celebrations. As the Church moves through the year, from the nativity of the Theotokos (Sep. 8) to her falling asleep or ‘’Dormition” (Aug. 15), the scriptures are carefully selected and proclaimed to God’s people, imbuing a meaning that is often inescapable and plain.

The ministry and life of Christ is made present for us in our prayers and hymns, and the illumination of scripture shines brightly in this communal experience.

Advocates of solitary methods such as the grammatical-historical approach (which has its uses, to be sure) will argue that you can find this ‘archaeological’ approach in the early Church Fathers, or in other ecclesiastical writers such as Origen. But as Louth notes, the intention of Origen was not to “get back to” an original text, but to rather gather every edition of the text in one place, so that all could be appreciated, studied, and proclaimed as valuable:

In the third century, Origen gathered the various translations together and laid them out in six columns, in a vast work of scholarship called the Hexapla. Its purpose was not, as is often asserted, to enable Origen to establish a text more correct than that of the Septuagint, but rather to lay bare the richness of meaning contained in the Scriptures of the Old Testament . . . there is a long process of exploring everything there might be in the witness of the Hebrew Scriptures to the coming of Christ.[2]

In the Eastern Orthodox tradition, there is a “tiered” approach when it comes to both the study and apprehension of our biblical texts. Beginning with the Gospels as central–since they bear witness to the very words and works of Jesus Christ–the Church receives and proclaims the full spectrum of scripture, and each in their own right,

[N]ot as some flat collection of infallible texts about religious matters, but rather as a body of witness of varying significance — some clearly crucial, as witnessing very directly to Christ, others less important.[3]

Louth also explains how the shape or ‘priority’ of these texts is played out in the worshipping life of the Church:

The criteria for importance are bound up in some way with the way the Church has taken them up into her experience. There is a hierarchy, a shape: the Gospel Book at the centre, the Apostle flanking it, and then a variety of texts from the Old Testament, generally accessed not through some volume called the Bible, but from extracts contained in the liturgical books, along with other texts: songs, passages from the Fathers, and so on. The Scriptures then have a kind of shape, a shape that relates to our experience of them.[4]

Those familiar with Orthodox, Catholic, or other “high-church” liturgies are familiar with the central role played by the physical Gospel book in rites and processions. Both visibly and in our hearing of its words, the centrality of the Gospel is paramount. This gilded book is venerated, kissed, carried about, and placed with reverence on the center of the altar, the place of greatest honor in our church architecture–a place symbolic of the Holy of Holies and, ultimately, the eternal sanctuary of heaven.

Instead of seeking only one ‘method’ for understanding the scriptures, we prefer the Patristic, four-fold approach: literal, moral, allegorical, and anagogical:

- The literal reading of scripture is the ‘plain’ understanding of an event. When Jesus walked into the wilderness, he walked into the wilderness. When Peter goes up to his rooftop to pray at a certain hour, this is simply what took place.

- The moral is most commonly found in Orthodox homiletics; that is, the moral implications of a Gospel or Epistle as applied to the congregation for inspiration to both moral behavior and true repentance. For those more familiar with the evangelical preaching tradition of the past few decades, this would be the sermon’s ‘application’ or how we take what we’ve heard from scripture and apply it to our day-to-day lives.

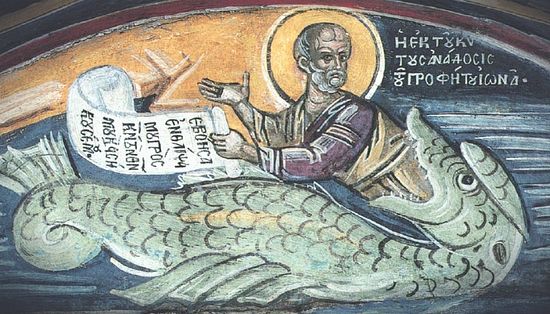

- The allegorical approach is found in many of the scripture readings for Great Feasts, and particularly during Holy Week. When the Church reads nearly the entirety of Jonah on Holy Saturday, Jonah’s three days in the belly of a sea monster is an analogy for Christ’s three-day descent into hades (which is commemorated on that day). The same can be said regarding the prophetic temple of Ezekiel and the Theotokos, Jacob’s ladder, and Noah’s ark. Instead of focusing on the literal fact of these events, the Church shows forth their deeper meaning for us as Christians–for all scripture points to Christ, and the Old Testament is our own story in him.

- The anagogical method is an elevation from visible events to the spiritual and eternal. This hermeneutic, much like allegorical or literal, can be also applied to the Divine Liturgy in its Patristic interpretation. The anagogical approach, like holy icons, shows the world as it truly is–as it is in eternity, and at the Last Day when Christ renews the cosmos. While our hearts are often troubled by this present, evil age, the anagogical approach tasks us to ‘lift up our hearts’ and ‘lay aside all earthly cares.’

Orthodox Christians have too high a view of the scriptures to limit them to only a literal or “analytical” interpretation. Hermeneutics is not a science, nor is it a discipline for academics (though they might feign as much). We believe that holiness–and not Ivy League education or a knowledge of Ancient Near Eastern history, as I’ve argued elsewhere–is the true key to their proper reception and understanding.

If we really believe that the scriptures are inspired by the Holy Spirit, then it is only through deification or theosis–acquisition of that same, eternal Spirit–that one may be attuned to the voice of God within. It is an historical irony that Christian groups founded on a respect for the scriptures as God’s Word would then turn upon their own foundation with both skepticism and an anxious scalpel.

This is why the scriptures are best read, heard, preserved, proclaimed, and understood within the context of the life of the Church and her holy Liturgy. For here they live, breathe, and have their being.