The Judaism of the first century was a religion almost entirely centered around the sacrificial worship of the temple.

Faithful pilgrims traveled many miles from all around the diaspora to worship at the temple several times a year, and the temple was central to their faith and piety.

While various forms of post-Christian Judaism today are more centered around the study of text—especially as might be seen in rabbinical Judaism—this was not the case in the lifetime of the apostles and early Christians (prior to A.D. 70). At this time, it was only the scribes and priests who had the ability to study both the scriptures and other religious texts:

It is natural that people often assume that Judaism in the Second Temple period was more or less like contemporary Judaism, in which people meet weekly or even more frequently in synagogues to pray, worship and hear the Bible read . . . Yet the Judaism of pre-70 times was formally structured in a quite different way from the Judaism of later times. The main religious institution was the Jerusalem temple, and temple worship went back many centuries in Jewish and Israelite history. The temple was not the same as a synagogue. The main activity in the temple was blood sacrifice. —Grabbe, An Introduction to Second Temple Judaism, p. 40

Many Christians today will associate a text-centered focus with Biblical worship, but this was true neither for the contemporary Jewish people of that era nor the early Christians. In fact, a robustly Biblical worship is one that resembles the temple cult as fulfilled in Christ, and not what one might find in contemporary Protestant or even Jewish circles.

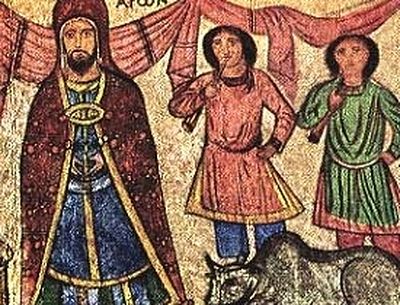

The worship given by God to his people in the old covenant was one of ritual, liturgy, sacrifice, and bodily movement—it was holistic, and it left an effect on its participants: body, soul, and spirit. People were moving about, engaged in processions, bowing, making prostrations, and burning incense. There were sacred images, statuary, and a number of other decorative appointments. And at the heart of Jewish theology and worship, of course, there was blood sacrifice. Being entertained was certainly not a focus of worship, nor was sitting down for forty-five minutes or longer to hear a sermon preached.

And interestingly enough—despite modern claims to the contrary—this “religious stuff” was not done away with by Jesus and his apostles. To worship in Spirit and Truth is not to worship in a way completely contrary to everything that has preceded us as God’s people. Jesus did not come to abolish the Torah and its worship, but to fulfill it in himself. He is the new Israel and the new Temple.

Since old covenant worship was patterned after heavenly worship, what sense does it make to write it off as superstitious? Shouldn’t our desire be to worship on earth as it is done in heaven (so far as it has been revealed to us)? And in heavenly worship, there are processions, angels, images, incense, antiphonal singing and chanting, and all the other elements of ancient, Biblical worship. There was not a complete shift away from liturgical or sacrificial worship to that of entertainment, sermons, and reflection—rather, the worship of the old was fulfilled in the new. What was once only a shadow was now made fully apparent through Jesus Christ.

Grabbe also notes:

The emphasis on blood sacrifice should not be misconstrued, as abhorrent as the practice may seem to some. It was not ‘empty ritual’ as so often portrayed in prejudiced Christian (usually Protestant) propaganda. On the contrary, the sacrificial ritual was suffused with deep religious symbolism. This symbolism was taken up into later Judaism, after the cessation of the temple cult, and into Christianity. The central Christian metaphor is, after all, the sacrifice of Christ — which has little meaning if the Israelite sacrificial system is not taken into account. —ibid., p. 41

Without understanding how the people of God worshipped at the time of the apostles (and prior), there can be no understanding of how Christians worshipped from that point forward—or why they did so.

Instead of completely abolishing the temple worship, it was fulfilled. And the essence of the temple itself is not eliminated, but is rather stretched throughout the entire world—everywhere Christians are gathered in the liturgical sacrifice.

The Holy Land is no longer confined to the land of Palestine, but is now every place that Christians are gathered around the altar of God. Our most pure and true pilgrimage today is a pilgrimage to a local celebration of the holy Eucharist. Orthodox worship sanctifies the space where Christians are gathered, just as the temple was a place set apart for the glory of God in the old covenant.