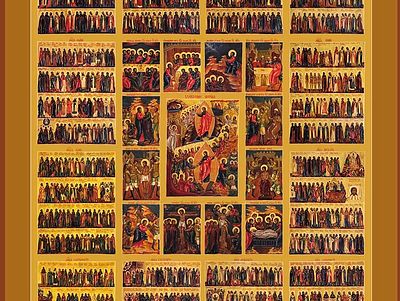

The Orthodox Church has a long tradition of honoring the Saints.

While all of God’s people, sanctified or “set apart” from the world, can be properly termed saints (e.g. Acts 9:13,32,41; Rom. 1:7; 1 Cor. 1:2; etc.), there are some who are already glorified in Christ, resting in the uncreated light of God’s eternal kingdom.

These are luminaries of the Church, shining forth among the darkness of our world, even during this temporary sojourn. They fought the good fight; they finished the race; they kept the faith (2 Tim. 4:7). Even in their repose, they are more alive in Christ than we. And it is to these known (and unknown) Saints that we look for not only inspiration and encouragement, but also for intercession; as enduring examples of how to speak, live, and die like Christ.

Some Christians object to the idea of honoring Saints—whether that be venerating their relics and images, or asking them for their prayers—because they feel it is to ignore the living already with us in the Church here on earth. They will suggest that a danger lies in only “speaking with the dead,” as the dead either cannot or will not talk back to us, redirecting us when straying from the straight-and-narrow.

But is this really the case? Is the danger real, or is it a misguided fiction? On the contrary, I think the danger is far greater without the Saints.

Growing up Southern Baptist, I spent a lot of time in our parish youth group. Practically every Baptist church in the Bible Belt has one, and they are where teens and young adults not only socialize but also learn more about their faith. The youth group leader, often a 20-something recent graduate of seminary, was more than just a leader to these teenagers; he was a role model, a mentor, a confidant, and a friend. Many students placed much of their identity in this person, not to mention their identity or hope as a Christian.

And in this veneration of a still-living person comes a great danger: What happens when he fails? When a scandal erupts? When there’s conflict, or a messy “falling out” between he and a particular congregation?

This happened more often than I care to recall, and it was a result of everything from marital infidelity (affairs with teenage girls in the youth group, for example) to other forms of financial or inappropriate dealings. And in the aftermath, the faith of many students was also laid to waste. Their greatest role model, friend, and spiritual leader had revealed himself to be a charlatan and a liar. Their personal faith was wrecked just as much as the life of this leader, or their youth group thereafter.

This sort of tragedy and loss of trust can occur in a number of situations, of course, and is not limited to just one type of faith or organization. But the point remains that trusting in those who are living is not always a “safe bet.” In fact, the safest “bet” of all is looking to those who, as St. Paul writes, have fought the good fight and finished the race—a race that is set before each one of us as Christians.

And in both Christ and his holy Saints, we have such examples; we have such sureties of faith, role models who will never fail us or let us down. People who can help us every step of the way in our mortal race towards Paradise.

Consider for a moment the prospect of being arrested for your Christian faith. You are a single mother or father of three young children—three young daughters. You are forced to decide between two choices: The first is to have your daughters executed before your eyes—one after the other. The second is to publicly deny Christ, offering worship to a false god instead.

What do you do? Do you watch the life drain from the faces of your precious children, as they cry for mercy? Or do you deny Christ? It isn’t easy to even thinkabout such a horrifying scenario, and many of us would like to believe we’d have the spiritual fortitude to make the right choice.

But would we? Would our clergy or spiritual fathers? Would our spouses and closest family members, those who we look to for not only guidance but also emotional, psychical, and spiritual strength?

During the persecution of the Roman Emperor Hadrian (ca. A.D. 126), a mother named Sophia was actually faced with this decision: to let her daughters be killed, or to deny Christ and worship Hadrian. As converts to Christianity in Italy, Saint Sophia and her three daughters—Pistis, Elpida, and Agape, ages twelve, ten, and nine—were granted to suffer for their faith. Sophia had to watch as her daughters, from oldest to youngest, were slowly tortured and then beheaded. After three days of mourning at their tombs, Sophia herself reposed in Christ.

Can you imagine the suffering? The horror? As a parent, I can barely stand to ponder it. And yet, this is why we need the Saints. This is why we need their examples, not only as a reminder of how to live for Christ, but even as a stark reminder of how to die—how to suffer with Christ as co-heirs of our eternal inheritance in him.

With Saint Sophia, we don’t have to wonder what we or anyone else might do. We don’t have to see our faith and hope scandalized by the wrong—albeit staggeringly difficult—choices of another. We don’t have to let our confidence sink to the depths as we are faced with our own persecution or suffering in the here-and-now; in the confusing tension between the already and not-yet.

With Saint Sophia, and the horrors she endured for the sake of not only her own salvation, but that of her triumphant, martyr daughters, what situation in our lives is beyond her intercessions? What difficult circumstances will we face that she couldn’t herself understand, or with which she couldn’t empathize?

This is why we honor Saints like Sophia; this is why we ask for her holy prayers, and the prayers of her three righteous daughters—daughters who perished so young, but are yet victorious over death itself in the risen Jesus Christ. We have assurance that the prayers of the righteous are powerfully effective (James 5:16), and there are none more righteous than the Saints.

Again, we honor the Saints because they have endured to the end. As those who have finished the race, they wisely pray that our every step might be guided to the finish. Because they have finished the race set before them, they are now resting in the glory of Christ in heaven—in the very presence of the all-holy and blessed Trinity. A place where there is no sickness or suffering, no sorrow or sadness, no death or disease.