Understandably, there have been several articles, podcasts, press releases, videos, and other media in recent weeks for the meeting between the Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew and Pope Francis, the present archbishop of the city of Old Rome.

The Patriarchate of Constantinople has spared no expense in promoting this event, which commemorates the fiftieth anniversary of a similar meeting in Jerusalem between the Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras and Pope Paul VI (January 1964).

For many, this event is little more than a well-leveraged commemoration of an extended olive branch between these two ancient, Christian faiths. For others, concern over the future of their respective churches takes center stage. Will this event be used as an impetus for doctrinal compromise? Will the future of either Eastern Orthodoxy or Roman catholicism hang in the balance as a result of this pending exchange of pleasantries?

What concerns me most is not this event in particular, but the language and statements being made by those on either side of the proverbial ecumenical ‘fence.’ I am fully in favor of a ‘dialogue of love’ and mutual respect between both Romes—Old and New. But when it comes to doctrinal compromise or even dialogue, we must be far more careful. The post-doctrinal Rome of Vatican II is not the ‘stodgy’ church of Trent—but this means she is far more slippery.

The script behind this dialogue is not new. Going back to the councils of Basel, Ferrara, and Florence in the mid-fifteenth century, attempted reunification of the Orthodox churches of the East and the See of Rome has a storied past. But in every age, and at every turn, a Saint has emerged to preserve the apostolic faith in spite of frenzied attempts to usher in its demise. While some in the age of pluralism might prefer to forget, the Church honors three of these Saints as the ‘Pillars of Orthodoxy.’

Despite her best attempts at the contrary, the gates of Hades have yet to prevail against the Church of Jesus Christ. And if the Son of God is to be believed, they never will. This is an important, foundational belief to the Christian faith—it is not tangential or secondary. Ecclesiology is Christology, and when we begin to separate the two, we begin to separate the Church from her very Head and Life. This is not ‘extreme’—this is Christianity 101. This is our Baptismal confession.

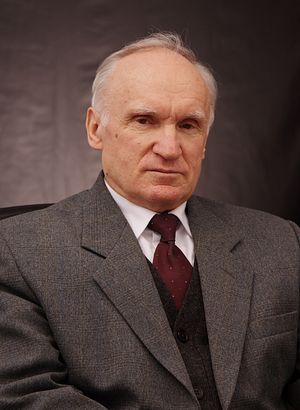

Professor Alexey Osipov

Professor Alexey Osipov

In his lecture, the professor focuses almost singularly on the topic of glorified (or ‘canonized’) Saints. In the recognition of Saints, the Church reveals less about the glorified figures and more about herself. By revealing to the faithful a person worthy of both veneration and fervent petitions, the Church reveals her inner being; she reveals what she believes about God himself:

Indeed, any Local Orthodox Church or non-Orthodox church can be judged by her saints. Tell me who your saints are and I will tell what your church is. Any church calls as saints only those who realized in their life the Christian ideal, as this Church understands it. That is why canonization of a certain saint is not only testimony of the Church about this Christian, who according to her judgment is worthy of the glory and suggested by her as an example to follow. It is at the same time a testimony of the Church about herself. By the saints we can best of all judge about the true or imaginary sanctity of the Church.

Osipov goes on to then describe in detail both the writings and actions of several ‘saints’ of the Christian West; that is, of the Roman catholic church.

In this evaluation, he unapologetically draws a pointed line of demarcation between both Orthodoxy and Roman catholicism. When we look at certain ‘Doctors’ of the Roman faith, such as Catherine of Siena (fourteenth century) and Teresa of Avila (sixteenth century), we see—per professor Osipov—spiritual prelest, an open door to demonic deception, and an assurance of glory that rivals Christ himself.

Of Teresa specifically, psychologist William James once wrote:

[H]er understanding of religion was reduced to endless flirting between the worshipper and the deity.

This is no exaggeration, with Teresa herself revealing innumerable ‘flirtations’:

From this day you will be My spouse . . . From now on I am not only your Creator, God, but also the Spouse . . . The Beloved calls my soul with such penetrating whistle that I cannot overhear it. This call so touches the soul that it breaks down with desire. —Spanish Mystics, p. 88

In a drawn contrast, Osipov numbers great ascetics of the Orthodox tradition who spend their entire lives asking for yet one more day to repent. At the end of his life, Francis of Assisi remarks, “I do not know any transgression of mine that I have not atoned by confession and repentance,” while St. Sisoes of Egypt laments: “Verily, I do not know, if I have at least started the cause of my repentance.”

The mystical theologians of the Orthodox ‘East’ have routinely condemned this prelest or spiritual ‘flirtation,’ so exemplified by the doctors and saints of Rome. For example, in the writings of St. Nilus of Sinai:

Do not desire to see sensually Angels or Virtues, or Christ, otherwise you’ll go mad taking a wolf for the shepherd and bowing to demon-enemies. —153 Chapters on Prayer 115 (Philokalia, vol. 2)

And again, in St. Gregory of Sinai:

Never accept things when you see something sensual or spiritual, inside or outside, even if it has an image of Christ or an angel or a certain saint . . . The one who accepts it easily gets seduced . . . God does not resent one being attentive to himself, if one fearing to get seduced does not accept what He gives . . . but rather praises him as a wise one. —Hesychast Instruction (Philokalia, vol. 5)

Osipov concludes:

Unfortunately, the Catholic church has lost the art to distinguish the spiritual from the sensual, and sanctity from reveries, and thus also Christianity from paganism.

Since the 1970s, and especially since the fall of the Iron Curtain, dialogue between Rome and Orthodoxy has accelerated at an expected, and even profitable level. Many concessions have been made on the part of the Vatican with respect to the Filioque clause, for example, while a rediscovery of the Greek fathers has influenced Roman theologians like Benedict XVI, the (rare) Pope emeritus. A full transformation is far from reality, but the theological ‘direction’ of Rome is more ad Orientem than ever before.

Nevertheless, the walls that divide are real. They are neither the mere fantasies of ‘extremists’ nor the hobby horses of ‘radical traditionalists.’ A divide between both Rome and the East is palpable; it is definable; it can be clearly laid out and explained. Despite all of the advances in recent memory, there are real, meaningful, and importantdistinctions between Roman catholicism and the holy, apostolic, Orthodox-Catholic Church of the Christian ‘East.’

Many would immediately draw these distinctions by looking to the age-old signs: the Filioque clause, the mandated celibacy of clergy, azymes vs. the leavened artos of the New Testament, Papal supremacy/infallibility—and so on. But I tend to think the differences are more subtle and yet, strangely, more infectious.

The differences of both doctrine and piety lie not solely between altered Creeds and disputed Councils, but in our affirmations of who best represent our respective faiths.

Reveal your Saints, and you reveal your Church. And in this conversation, a difference between ‘East’ and ‘West’ could not be more pronounced.