Source: The Dallas Morning News

September 24, 2015

Leonidas Diamantopoulos put brush to a large canvas spread out on the floor of his Athens studio, etching out images of a pool of water and a man standing beside it. Slowly, the story started to come together.

He’s not painting pictures, he said. He’s writing stories.

Every so often, Diamantopoulos stood up and ascended a small spiral staircase. On a second-story balcony, he can look down at the image — better perspective for how it will look on the ceiling of a Dallas church.

“Someday after I finish the whole project, I’m sure this church will be a landmark site for Texas,” he said.

After years of planning and fundraising, the icons are being prepared for Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church in Far North Dallas. It took a year and a half for Diamantopoulos and three assistants to write the icons before rolling them in bubble wrap and sending them halfway across the globe to Texas.

In Dallas it takes a crew of six, including Diamantopoulos, 20 days to attach the canvases to the walls with special adhesive.

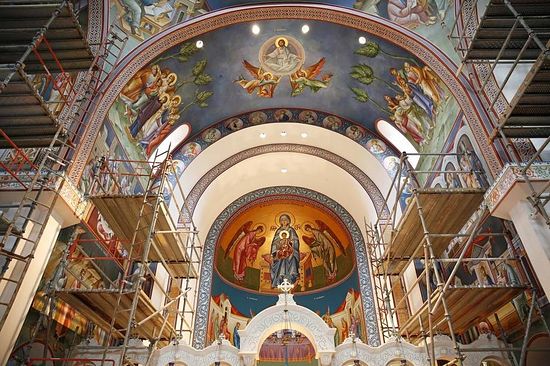

Tall scaffolding line the transepts of the church — the east-west arms of the sanctuary — where the iconographer and his crew stand high above the pews and roll out the canvases he created back in Greece.

One, with the pool of water, is hung on the north side. From ground level you can see it clearly — Jesus washing the feet of his disciples before the Last Supper.

“Iconography is theology in color,” said the Rev. Christopher Constantinides, presiding priest at Holy Trinity. “You can’t tell me you walk in here and not be moved.”

When he was younger, Diamantopoulos wanted to be a lawyer. He was at law school in Athens when he met an iconographer and visited his studio out of curiosity.

He was so interested in how the master artist worked, he went back for coffee again and again. In his final year of law school, he dropped out and began training as an artist.

Two years of art school turned into six years of apprenticeship with the iconographer before he set out on his own.

“After I discovered iconography it was double, how do you say, two things at once,” Diamantopoulos said. “I am in love with the church. Also, I am in love with art.”

Now, 40 years later, he’s a world-renowned iconographer with works in churches all over the globe. He travels whenever he’s not working in one of his studios to meet with churches and install the icons. After he’s done in Dallas he has appointments in London and Barcelona.

“I feel a great responsibility through the iconography here to [pass down] faith for the next generations,” Diamantopoulos said. “I don’t call this a business. It’s a ministry.”

He mainly works with Greek Orthodox sanctuaries but has also installed icons for Serbian, Antioch, Ukrainian and an Indian Orthodox church in Chicago.

One of his largest works, the Assumption of the Theotokos Cathedral in Denver, features huge images of Christ, the Virgin Mary and dozens of saints. It’s been compared to the Sistine Chapel, Diamantopoulos said.

“Of course, I’m no Michelangelo,” he said, “but I’m doing my best.”

Orthodox iconographers work within the confines of strict dogmatic rules. The style of the art is set. The brush techniques and installation have been passed down for centuries. Even the placement of the icons in the church has to be regulated.

For example, in the apse — the rounded alcove behind the altar — of the sanctuary there must always be a large image of the Virgin Mary. In the dome of the church, there must be an image of Christ, surrounded by saints or angels.

Diamantopoulos meets with church officials to take measurements and plan the icons. He offers suggestions which are usually adopted, he said, “because I’m the expert in this kind of work.”

He’d been to Holy Trinity before and had installed the first phase of iconography in the mid-1990s when the church first opened. As the church approached its 100th anniversary, Constantinides had a specific vision for how he wanted the sanctuary to look.

In the back of the church, over the choir loft, he wanted Old Testament stories like Noah’s ark. He wanted the stories to depict the New Testament down the main aisle, with the Passion and Crucifixion at the front in the transepts. Then, in the apse, Constantinides wanted to see stories about the Resurrection.

“It’s a process, I’m telling you,” Constantinides said. “This is not decoration. The church is helping tell a story.”

Fundraising for the new iconography started a few years ago. The church sold sponsorships for individual saints or scenes, collecting donations piece by piece. When they had enough in the bank to complete the transepts, Constantinides called Diamantopoulos in Athens.

Diamantopoulos paints on canvas because it’s better and cheaper for the church. Spending his time writing icons directly on the wall can take up too much time. And if something were to happen to the church — water damage or cracks in the ceiling — the canvas can be taken down to do repairs, rather than repainting the entire work.

Taking care of the icons is precarious as well. Diamantopoulos treats the canvas with four liquids to make it water-resistant and keep colors vibrant for centuries. Wax paper is taped over the 22 karat gold-leaf halos on the holy figures for the long trip over the Atlantic.

Here, the icons rest in a pile of 10-foot long rolls, waiting to be carried to the top of the scaffolding and placed carefully on the sanctuary walls.

“For me,” Diamantopoulos said, looking up to the ceiling at Holy Trinity, “icons are the tool, the way to lift your spirit up from the material world to the spiritual world.”