A group of sixteen pilgrims from England recently made their way to Russia to explore the spiritual treasures of Moscow, and particularly those relating to the lives of their parish patron St. Elizabeth the Grand Duchess and New Martyr, and all the New Martyrs and Confessors who suffered under the Communist Yoke in the twentieth century.

They took some time out of their busy schedule to chat with us at Sretensky Monastery and offer their thoughts and reflections on their trip, as well as the history and current state of Orthodoxy in England.

Comments by pilgrim John Harwood are introduced simply with "—", those by his wife Maria with "—(M)", and those by fellow pilgrim Paul Oxborrow with "—(P)".

—Tell us about the group you’re here with and the community in England

—The community that we come from, which nearly all of us are attached to in some way, is a small chapel on the south coast of England in Sussex. Technically it’s the bishop’s podvoriye but in fact it’s really just the local Orthodox community, with one nun, Mother Martha who’s with us now. We had a priest but unfortunately we lost the priest who lived locally—he’s gone to live in the Netherlands, so now we have a priest who comes from Oxford because the bishop can’t find us a local priest yet. So we just have two services a month now which is very sad. We used to have many, frequent services.

So that is our group. Some of us are not Orthodox but are very interested. There are four non-Orthodox and one of them is particularly close. The rest of us are Orthodox—some English, and all sorts of different ethnicities. Mother Martha is Russian. We have a Belorussian lady. Maria, my wife is Russian. We have a Bulgarian man who is very nice who goes on pilgrimages frequently. He’s always somewhere exciting and interesting, and the rest of us are English—several converts to Orthodoxy. Our priest, Fr. Stephen, is absolutely English. We have with us a girl who has lived nearly all her life in England but is of Russian parentage. So that is our group—a mixed and friendly group.

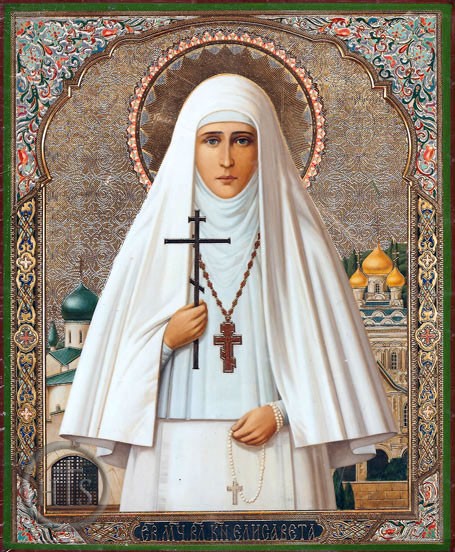

—And who is the patron saint of your community?

—Our community is the New Martyr Grand Duchess Elizabeth, and all the New Martyrs of Russia. Originally there were great plans of having two altars so that’s why we have two dedications. Our pilgrimage is, in fact, centered on the New Martyr Elizabeth and the other New Martyrs. So we’re going to the Martha-Mary Convent, and this afternoon we came here to the New Hieromartyr Hilarion.[1]

—Yes, we’ll go to Butovo, Novospassky …

—(M): And also to places connected with the life of the Grand Duchess Elizabeth and Sergei Alexandrovich.

—My wife is very interested in the life of the couple when they were married before the assassination of Sergei Alexandrovich, so we’ve seen various places from their lives.

—(M): We were at Neskuchnii Sad today where they had a house where the headquarters of the Russian Academy of Sciences is now, and the governor-general house on Tverskaya. We have people with us who have never been to Moscow, so this is also an opportunity to see all of the city.

And Sretensky Monastery is important for us of course because of the New Martyrs,[3] and especially St. Hilarion Troitsky. And we were very excited to see this new church.[4]

—Yes, it’s very wonderful and we hope to come back and see it when it’s completed. But the whole itinerary was very expertly organized by Maria and it’s really turning out so far to be a great success, and we hope it will continue to proceed the same as it has these two days. And our last day we will see the Moscow parish house—the Patriarch recently consecrated the church. It’s the eparchy headquarters, and it has connections with the Council of 1917 where some of the meetings were called. I believe it’s the administrative headquarters for the Moscow Diocese.

—(M): And of course there is the Martha and Mary Convent, which we will visit tomorrow for the Sunday Liturgy. That will be a high point in our pilgrimage and we will be shown around the convent and meet the sisters. We are very excited about it.

John is an expert on Orthodoxy in England and he has written a lot of articles. He knew people who are now saints such as St. John Maximovitch, and he also knew Fr. Nicholas Gibbes, who was the English teacher for the Tsar’s children.

—Fr. Nicholas died in England of course.

—And Fr. Sophrony?

—Fr. Sophrony I didn’t know very well. My whole background is with the Church Abroad. I only started to be close with the Moscow Patriarchate in the past twelve or fifteen years when we were getting so close to the union that it was obvious it was going to happen. But before that my whole life I was with the Church Abroad, so I knew lots of people from the old days who remembered how things were before the revolution.

The bishop who was bishop when I first became Orthodox actually remembered attending liturgies of St. John of Kronstadt. Can you imagine?

—That’s amazing! Could you share some of your memories of St. John, or what this priest remembers about St. John of Kronstadt?

—He remembered it wasn’t all happy as the books tell you. There were many people who were very opposed to St. John of Kronstadt and when you went to the church there would be crowds of people outside making a big row and shouting and telling people not to go to this nonsense. There were always many disturbances around the church doors. A lot of people were very opposed to him for various reasons—political reasons, because he was a strong supporter of the monarchy.

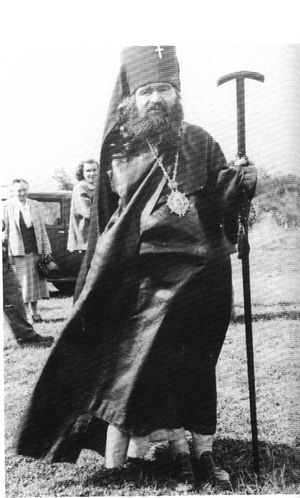

—How was it that you knew St. John Maximovitch?

—He was actually the local bishop when I first became Orthodox.

—In England?

—No, but England was part of his diocese. He had the title then of Bishop of Brussels and Western Europe, but I don’t know why Brussels. He never lived there. He lived in a tiny Russian house in Versailles, outside Paris. He used to come over a few times a year on the big days to serve. Then after he went to America they split England and made it a separate diocese, but while he was here it was part of his diocese. So he was our bishop. I remember the services beginning with a long list of hierarchical names. We would remember Metropolitan Anastassy who was still alive until 1965. I don’t know how old he was—he’d been a bishop for sixty years—can you imagine? It was a unique length of time.

—(M): It was he who wrote the first work about the Grand Duchess Elizabeth. He realized her importance and her personality. I always come back to his article.

—And he was a poet. He wrote several poetic pieces in her memory. He was a very cultured man.

Anyways, there would be this great string of bishops. They would commemorate Met. Philaret because Met. Anastassy had retired, and then Abp. John, and then Bp. Nikodim who was the vicar bishop.

—(M): Why don’t you tell him about your spiritual father?

—My spiritual father was a most interesting man—Fr. George Sheremetev, from the family Sheremetev.

—The airport family? There is a major airport in Moscow named Sheremetovo.

—Yes, absolutely. He went from being one of the wealthiest young people in Moscow to being penniless. He had a cardboard suitcase that was very feeble. He showed me and said, “This was all I was able to bring, and when I find I can’t get my possessions into it, I throw some away, so that everything fits into it.” And this was a man who before the revolution used to come to England three times a year to get new suits—once for the first fitting, then for a second fitting, and then the third time to take it home.

—I was at the Sheremetevo palace a few weekends ago. To go from that to a cardboard suitcase is indeed a huge change!

—Absolutely. Yes I used to go to him for confession and he lived in a tiny flat in Kensington that had been given to him by some wealthy person, and it was just a tiny room—there wasn’t even room for a table, and he would just sit on the edge of the bed because there was nowhere else to sit.

—Did he give any typical advice that you can remember?

—Oh yes, he said lots of memorable things. He used to say, “Never let the words of the Gospel become stale by over familiarity. And if you find that they do, that you know them so well that they’re not getting through or striking you at all, stop reading them and read them in a language you don’t know very well.” For me it wasn’t difficult to find such a language, and he said that you’ll be forced to slow down to such an extent that you’ll find something fresh. This is wonderful advice that I’ve never heard from anyone else. Yes, he had wonderful things to say.

—(M): Our Fr. Stephen inspires us to use two languages, which is usual in England—Russian and English during the service. He says it’s very important for you to listen to Slavonic if your native language is English, so that maybe you’ll get some fresh understanding of the Gospel, and vice versa for the Russians—don’t be angrered by too much English, because it’s’ very important for you to listen to these familiar texts in a language which you’re trying to understand; and in comparing, new ideas come to you—“Ah! This is how it sounds in English,” and “Oh, do we understand the same in Slavonic?” So, it’s quite an interesting experience that we have with our various languages.

—Another pilgrim with us is Paul who has been Orthodox for a very short time, and I think maybe his perspective could be interesting.

—(P): I don’t have a great deal to say. I’ve been Orthodox for about two months. I’ve been coming mostly to the Greek church for about eighteen months, but also to the Russian church. I find the whole story about the Grand Duchess Elizabeth very inspiring and I’m very interested to find out more about her life.

—Of course she also had English blood.

—She was English in a way, because her mother had enormous influence on her and she was English. I think she was more at home with the English language than with German. I don’t think they used much German in the family—only with her father.

—(M): Maybe sometimes with her sister too, but the biggest part of her letters are written in English. Her letters to Tsar Nicholas are in English. And she had English servants.

—On our site we often post lives of the western saints. Did the English pre-schism saints play any role in your conversion, Paul? Or is there much veneration for them in your communities? Is there much awareness of them?

—We have been on pilgrimage to several local saints. We do it less now because we don’t have a priest that’s close to us, but we did go on a number of local pilgrimages and they were very successful. The authorities of wherever we went were very kind to us and allowed us to have molebens and so on at the sites of the saints.

—(P): I think there’s an awareness of them.

—Yes, much more so than when I became Orthodox. Greeks and Russians were only interested in their saints and would have had a horror at the idea of adding these saints to their calendar, but now everybody adds the western saints to their calendars, and icons are painted. Wherever you go now in Western Europe you find Orthodox have been there and have left icons at these places. It’s a great change.

—(P): I think it’s something that’s probably less pronounced in the Anglican and Catholic communities. People know about them but they don’t really play a very lively or active part in their spirituality or lives. But they’re there in the background.

—(M): There is a great deal of interest in things like icons. A local Anglican vicar, who had a church dedicated to St Mary Magdalene, asked us to bring an icon from Sofrino, and he very solemnly installed it in the church and asked us to show everybody how to venerate the icon properly, and this icon is still there. It’s in a little chapel. So there is a kind of influence. The Vladimir Mother of God and Christ the Savior are everywhere—St. Paul’s cathedral for example.

—At Westminster Abbey the first thing you see now when you go in is icons on either side.

—(M): And by the way, our saint, the Grand Duchess Elizabeth, is just above the main entrance at Westminster Abbey where they have martyrs of the twentieth century.

—Things have changed a great deal. People grumble a lot about how terrible things are, but things have changed in some ways for the better. For example, ecumenism that people get so worried about, when I became Orthodox was very one-sided. The Anglicans especially were very patronizing to Orthodoxy and thought they owned it, and would tell everyone all about it and not be interested in what the Orthodox said about themselves. Now that is gone. Now they’re anxious to get things form us, which was never the case. They would never have owned that they needed anything from Orthodoxy in the early 1960’s.

—(M): The most fascinating case was the previous archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, who was a Russophile and wrote a book on Dostoyevsky as well as many other articles on Russian spirituality. Recently we had a charitable concert in Paul’s house, and a Russian pianist came to play. Lots of rich people came, and they donated some money towards our community! And an icon of St. Seraphim was there in front of everyone because it was on his day. Everyone was quite happy about it. We met the former secretary of Archbishop Williams. We also have a number of people from Anglican and Catholic communities who regularly come to us. One of them is very remarkable.

— He’s a Catholic priest and he is an expert on all things having to do with the Russian royal family—he knows everything.

—(M): When you go to his house it’s like a temple to Tsar Nicholas and there are pictures of them all, and really he has some treasures, including some photos of Grand Duchess Elizabeth which he said he will give to us when he reposes, including an original portrait of the Grand Duchess.

—And he’s transcribed all sorts of diaries and unpublished things.

There’s a great interest. Some of it drifts into purely an interest in royalty. At its best it’s healthy but some of it is mixed up with worship of royalty.

—You said the bishop sends a priest to you from Oxford—how far are you from Oxford? Are you an Oxford community?

—We’re not part of the Oxford parish. It’s simply that the bishop decided that this priest could do it, because we needed a priest who knows Russian and English and not many in England know both. He’s in the south of England.

—(M): Our communities are quite inter-mixed though. Many people from Oxford come to our services. It isn’t near but people still come from there and we go there very often to their feasts. We know each other very well.

Actually, our community is a future convent. We have a nun, Mother Martha, who is on the trip with us, and she came there nine years ago and started living at this place. We still have hope that it will become a convent, but it’s very difficult to find nuns to increase the community. So for now it’s a parish attached to this hierarchical metochion. The place is unique. It’s beautiful, it’s a big space. It’s very interesting because it’s a very English place.

—English scenery, anyway.

—(M): There’s a very famous castle right next to us, so people come. All the south of England is our parish. Usually about fifty or seventy people come to the services.

—Mother Martha is wonderfully hospitable so we always have a beautiful trapeza. It’s a very pleasant place and the children like it.

—(M): The Oxford community was established by Fr. Nicholas Gibbes. He was the first Orthodox priest there.

—The Oxford parish was founded by Fr. Nicholas Gibbes who became a priest in Harbin, China, and later came to England and founded the first community in Oxford. He founded a chapel dedicated to St. Nicholas and then they had a combined parish with the Greeks under a different name, but now Fr. Stephen has found a beautiful former Anglican chapel, and he found that it had been dedicated to St. Nicholas, so it’s back to the way that Fr. Nicholas Gibbes wanted it to be. And that community has been well established for many years, from just before the Second World War. Of course there are other communities in the south of England, but these are the two that we know.

Fr. Stephen is the dean for southeast England and he has many university links as well. We’re very lucky to have a priest of such caliber—intellectual, spiritual, and linguistic. As I said, it’s not common to have a priest that knows both languages well enough to find it easy to switch back and forth.

—(M): He runs a wonderful summer camp for children, which is his pride and joy. And we also have Sunday school that we run. This is experimental and quite unusual for the Orthodox world because we teach over Skype, and the children live in so many different places. It’s very difficult to meet with them. Skype allows us to meet every week, and I can write on Skype in two languages to explain some terms, to open some new icons, etc. It gives lots of technological possibilities.

—If we have the technology we should use it for the glory of God. This is certainly the first Skype Sunday School that I’ve heard of.

What is the future of Orthodoxy in England in general? Do you have a sense of this, or is it all up in the air?

—A lot of people are still attached to their different national backgrounds. For instance, we have a very good Greek priest nearby, so that’s where we go on Sunday, and he is extremely near to us, knows our community, and comes up to help with confession when it’s a big day. He’s a wonderful man. But his community has other concerns and interests. I don’t think this business of jurisdictional unity is the main thing. When communities come together in worship, then things will change. In London people are very attached to their ethnic backgrounds because they’re recent immigrants. It’s a bit easier for us, but it’s still a problem. You can’t talk about Orthodoxy in England very easily.

—(P): It’s going to remain a minority I think. In a land where religious practice in general is going down, Orthodoxy is always going to be a minority of an increasingly dwindling [Christian] minority.

—The religious situation is very bad in England now. Churches are closing at a great rate. Even the Catholic Church, which always was very impressive from a point of view of religious practice, is now in severe decline. They have churches having only one Sunday service while they used to have six, with huge crowds of people going to them.

—(P): In that sense it’s possibly a bit of opportunity because I don’t think Orthodoxy suffers from that problem of inherited social position or status—it’s always an outsider.

—It’s the underdog.

—(P): Yes, the underdog. And I think thus it’s in a comparative position of strength and doesn’t suffer from the familiarity that breeds contempt; perhaps this an opportunity for development. I think also it has strength in the eyes of other Christians. Speaking for myself, I’ve always looked very longingly at various aspects of Orthodoxy and found it very appealing and attractive, without ever committing myself to it. And I think that’s probably true of a lot of Anglicans, and probably quite a number of Catholics.

—What got you to finally take that step?

—(P): I suppose it was both negative and positive. There was a sense of desiring a deeper spiritual life and not being able to find that really in my Catholic experience—feeling rather jaded, in despair of finding the life I wanted to lead as a Christian. So that was a sort of negativity about my experience as a Catholic. There was the sense that all those things that had appealed to me over my life about Orthodoxy were maybe pushing me in that direction, and the more I experienced of it—when I gave up going to Mass and started going to Liturgy—rather confirmed my feeling, and I felt that there was a possibility and a spiritual life which would be more meaningful and would make me pay attention to myself and where I was in a way that I had really failed to do previously.

—So maybe that could be true of many others if they could just get themselves to take that step.

—(P): I think there is a great disillusion amongst Catholics, at least in the pew in what they experience as religion. Or there ought to be. And that’s not true in Orthodoxy. You see that there’s something interior happening in people. There is spiritual direction happening, and prayer happening, which means people are taking it seriously. And there’s a great richness that you could just miss in the Western tradition. There’s a strength about Eastern religion that I found very appealing, and I think others would too if they could just move in that direction.

—I think some people are frightened of making the step because they think it’s such a different culture, and they get themselves into a terrible fix over this. All they need to do is to come along a little bit to see, and join in and they’ll find it’s not—they’re meeting ordinary people, they are not strange creatures from another planet …

—We might be a little weird.

— [Laughs] Well, just a little bit!

—(P): There are some cultural differences—the language, the whole style of everything is very strange and different, and can be quite opaque, and you might not understand what’s going on.

—But not quite as strange as they think it is.

—(P): But the more you get to understand what’s happening you realize that most of it is what you’d already been doing, in a different form.

—The outlines of the Mass and the Liturgy are basically the same.

—(P): Right. And most of what’s believed is the same; but when you go to Catholic Mass and hear the music and compare that with the music you hear in the Liturgy, there’s no competition.

—You’re not hearing Gregorian chant anymore, unfortunately.

—(P): No, and it’s not even nice chant of any sort. I think there may be an opportunity, but whether we’ll take that opportunity, I don’t know. It’s not an easy one to grasp and see what might be done. The fact that Christianity has retreated so far in our generation and the previous generation means there’s a great vacuum in society which is calling for something to fill it—it should be something good rather than something bad.

—(M): There is a very special case that we have in our group, which I must mention. One woman, who came with us, who is non-Orthodox, was simply my acquaintance and she and her husband wanted just to see Moscow. They booked this tour in May, thinking, “OK, we’ll join this pilgrimage to see the churches.” They’re not believers very much. In July this woman was diagnosed with cancer. And now she’s going to all the places we’ve gone, praying deeply. I think the same must happen to the Western society someday—people must come to the true Orthodox faith finding there this deep, religious experience.

—I think that’s a good note to end on. Thank you very much for taking your time to talk with us!