– Elena, tell us about how you came to faith in God?

– I would have to tell you my entire life story in order for it to make sense. I was born in an atheistic soviet family. By the way, that atheism was superficial. We believed in goodness and justice, as something that goes without saying. No one ever looked deeper into the source of this belief in our souls. A true atheist is a terrible being, deprived of morality, and obsessed with no more than his own material gain by any means. After all, he has nothing other than this earthly life; there will be no other life for him, and therefore he has to grab the maximum of goods and pleasures here. As Dostoevsky wrote, “If there is no God, then everything is allowed.” But we, of course, were never that kind of atheist.

When I was four years old, my father once pointed to the sky and said that it was infinite. I remember that it took my breath away. I began to think about it. Later, when I became interested in mathematics, I tried to apply the principles of that science to my search for truth. If you logically seek the first cause of anything at all, you will inevitably run into that emptiness from which everything originated. But emptiness itself cannot produce something outside of a certain mysterious power. In general I thought a lot about this, drew graphics with the beginning point of existence (racking my brains over the question, “But what came before that point?”), read various philosophers, and even created my own philosophical concepts. Then the Gospels somehow came into my hands. This book created an amazing impression upon me. I suddenly had a sharp perception that the truth was precisely here. It was as if I saw with my own eyes how Christ preached, worked miracles, was crucified, and resurrected. Truly resurrected! No such perception of reality has ever occurred to me with any other reading. Well, my eyes having been opened, I ran to the church, bought a stack of books, immersed myself in Church life, and began to “terrorize” my family and friends. I am a very emotional person and easily carried away; and of course, my missionary attempts at converting my parents took on a somewhat aggressive character at first. But with God’s help, everything eventually normalized.

It seems to me that any person who purposefully seeks the truth will come sooner or later to an Orthodox church, regardless of his nationality, ancestral religion, or other factors. The truth is simply here, and nothing else has meaning.

– Often newcomers to faith who have firmly decided to enter into Church life try through their zeal not according to knowledge to reach great spiritual heights, taking on asceticism beyond their strength. This usually has sad consequences. Were you able to avoid this?

– I made all the mistakes that could be made; because, as I said, I have a very emotional nature. When I understood that the truth is here, in Orthodoxy, I took off running it to meet it. It was like with the sports that I used to be involved in. I prayed and over-prayed… I threw away all my clothes, leaving only a long, black skirt, a formless sweater, and a faded headscarf. I renounced the fallen world. I had a crazy look in my eyes, and tried to convert everyone immediately. People simply ran away from me. But now I have calmed down. I live quietly, and perform no ascetical feats. I fast, but not as in a monastery, rather according to my strength. Without fanaticism. If I can get through the day without judging anyone or having vile thoughts, that’s good. I leave my close ones alone. Everyone has to go his own way. I can only attract people through my own example, and therefore I have to look at myself more, and not at others. I read an abbreviated prayer rule, I go to church every week and on the great feasts, and try to receive Communion once a month. I ask to be allowed, though unworthy. So far, they allow me. This is my rhythm.

– You are an author and playwright. Is it possible to write about the evil that surrounds us in a way that will not tempt those who doubt?

– I write in parables and place the accent on what I see as good and bad. My accents are definitely Orthodox Christian. I have one play, for example, about Khodja Nasreddin.[1] But in spite of its eastern flavor, this play is absolutely Orthodox Christian in accent. I took a particular blessing before beginning this work. After all, the characters in this play are not worshipping Christ. I was cautious about that theme. But they let me get into this story, and I am very glad that it turned out well.

– For whom do you write?

– I try to write in a language that worldly people can understand, those who are “not called to the King’s feast,” those who have not fallen into place spiritually, and are “sitting on the fence.” I know that state very well. We need to extend a hand to such people. We must not turn away those who are not yet with us, but who are no longer against us.

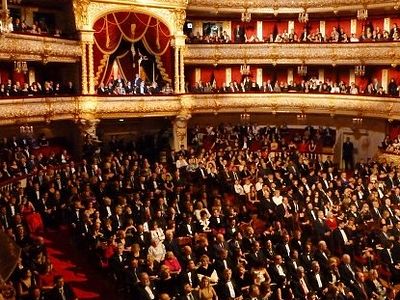

Although, my poem, “Song About Holy Prince Daniel of Moscow…” is a truly religious work, created, it could be said, at the request of the director of the Orthodox School of Art, Sergei Mikhailovich Mamai, and by the blessing of the school’s spiritual father, Priest Nicholai Pushkin. But I repeat that my creative work is mainly secular. I would say that it is aimed at those who came to the theatre and not to the church, so that they would want to go to church after watching the show. Or that they would at least think about something serious. After all, the most important thing is that they begin to think correctly. Then, with God’s help, good sense and thoughtfulness will take them where they need to go.

Of course my spiritual father, Fr. Nicholas (from the Church of the Icon of the Mother of God of the Sign in Peryaslavl Sloboda) knows about all of my creative searches. Batiushka’s wife, Matushka Vera, is the most valuable fan of my creative work in all its multi-faceted hypostases.

– What do you consider the most important mission of a cultural worker, an artist in the greatest sense of the word? And how does he keep from falling into the sin of vainglory?

– A true artist should transform the world, inspire it, uplift man above his animal nature, raise his thoughts to heaven, and reveal to him the image of God that is within himself. Bad art “animalizes” the viewer, arouses his instincts, and finally lowers his human dignity. Like the film currently popular in Russia, Stilyagi. It is a very talented film that wonderfully exalts vice. Would that we could exalt virtue just as brilliantly!

From their contact with a creative work, under its influence, people should become better, kinder, more merciful. Families should become stronger, alcoholics and drug addicts should become fewer, harlots should be changed… Any creative work should have a moral foundation under it.

Someone might ask, “What about the art flourishing all around us? Romanticized criminality, beautified debauchery, the charm of vice?” We should not orient ourselves toward what is flourishing around us. Check your actions against the reactions of your conscience. Your conscience will not deceive you. “O child of eternity, do not please the spirit of the times.”

How to struggle with vainglory? I do not know. My life seems to be such that it is hard to get overly vainglorious. All along my creative path there is always one person or another actively humiliating me, scolding me, or trying to prevent me from going on. Thank God for it, I suppose.

– Your play, Don’t Throw Ashes on the Floor, touches upon a painful theme in our country—drunkenness. You have thought much about the causes of this evil, and how to war against it. How do you think an Orthodox woman could help her husband who is unable to overcome his passion for drink?

– She can only help in such a situation with prayer. And with love. Hysterics and moralizing will only intensify his passion. A drinker falls into a vicious, closed circle: he drinks in order to forget his shame that he drinks. It is like the drunkard in the story, The Little Prince.[2] There is also the purely physiological dependency that develops, which is not so easy to break.

I have had an experience with this in my own life. I consciously married a man with a problem. I knew that he was a drinker, but I ignored that fact, assuming that we could overcome everything with God’s help. What is most important is that he himself had the desire to struggle. At first everything worked out beautifully, and I became overly proud. But later humility caught up with me; we were dealt a crushing blow, and his vice triumphed with renewed strength. I nearly lost my mind from despair. How many tears I shed… I was sobbing endlessly every day.

But now, when I analyze the situation from the beginning—that is, the decision to bind my life with him—I understand that is was all logical. And all in my style. I was looking for a podvig,[3] and rushed into it in a big way. But what is characteristic is that my former husband no longer drinks. At all. And I am sure that this is the result of his having stopped then. If he had not stopped, he would not be around today, most likely. A terrifying feeling of hopelessness exuded from him then, as if the finale was near. Of course, I could not just pass him by. I had to climb into the situation and begin saving a friend. Otherwise, it would not have been like me. But probably it was not a good idea to get married then. A marriage requires love. Christian love of neighbor is not enough for marriage. But during that euphoria of a temporary victory over vice, we both felt such an emotional upsurge that we mistook it for feelings of mutual love.

There is a certain story about Orthodox marriage, which migrates from one book to another. I am talking about the girl who brought various suitors whom she liked to her spiritual father, but the latter turned them all down. However, when the girl brought a young man whom she didn’t like at all, the spiritual father blessed her to marry him. So the girl married him out of humility, and twenty years later finally felt infinite love and gratefulness to this man for having provided such a happy family life. It is a good story, and probably has happened. But it should in no way be an example for blind emulation! That is the story that attracted and disoriented me then. Unanimity of views is a necessary condition, but it is not enough to create a family.

– Why do actors and actresses usually have troubled personal lives, and their marriages are not long-lasting?

– Because this profession is very bad for one’s emotional health. In the morning at rehearsal you love one person, in the afternoon at the shooting you love another, while in the evening at the show, you love a third. When you come home at night, you finally see your own beloved husband or wife, and you can’t understand who you really love. I have a play with this theme called, In Search of Lost Grig. The central figure is an actor who looses his own “self” in his roles.

When anyone comes to me for help in preparing themselves to enter a university level theatre school, I start by trying to talk them out of it. Acting is a dangerous field. It is an idle way of life, an outwardly easy existence… Bad endings… For every successful fate there are scores of broken ones. Even outward success often has a seamy side.

We play risky games. We play with life, with relationships. “Why are you so calm? Stir yourselves up!” That is what they would say to us in acting school. And we did stir ourselves up, because calmness is not a theatrical state. We would make ourselves look with lust at people of the opposite sex, because love between a man and a woman is the main theme of all theatre. But do you recall what the Gospels say about this? Whosoever looketh on a woman to lust after her hath committed adultery with her already in his heart (Mt. 5:28). We would intentionally arouse passions in ourselves, explode our tempers. The consequences of such behavior have been tragic.

The instability of actors’ and actress’s marriages are no coincidence. Non-traditional orientations are widespread. The problem of alcoholism is on a broader scale in acting spheres than anywhere else. Now drug addiction has been added. It has been added everywhere, but it is affecting actors and actresses on a grand scale. There are no official statistics; this is my own observation. But I am observing attentively.

– Does this mean that acting and Orthodoxy are not compatible?

– For the most part, of course they are not compatible. But on the other hand, The wind bloweth where it listest (Jn. 3:8). Acting is without a doubt a spiritually dangerous profession. A judge, for example, is also in a dangerous profession because he daily breaks the commandment, Judge not (Mt. 7:1). Or a teacher—My brethren, be not many masters [teachers], knowing that we shall receive the greater condemnation (Js. 3:1). But all these professions are nevertheless needed. People also need the world of culture, which means that those people who work in the arts are also needed, including actors and actresses.

– In your opinion, what should an Orthodox woman be like?

– It goes without saying that she should not be a sex-symbol. An Orthodox woman should be a symbol of virtue. But that does not mean that she is obligated to look like a bag lady. She should be beautiful, regal, decorous, radiating spirituality. Like our last Empress, Alexander Feodorovna Romanova. I mean the real one, and not the one in G. Panfilov’s film.

–Many Orthodox women (and men, for that matter) do not maintain their physical form, do not exercise or play sports, and consider all that unimportant (that is, not spiritual). You are a master figure skater, and studied as a child with the famous trainer, Elena Tchaikovskaya. A few years ago you were featured in a television program called “Aerobics,” where you introduced people to a healthy lifestyle. What can you say to people who have not experienced the “joy of fitness?”

– I would say that the body is the temple of the soul, and you can’t just let it go; you have to work on it. Of course, physical fitness should not turn into a goal by itself. No one needs any soulless Schwarzeneggers. But a rich inner essence should have an attractive outward form, in my opinion. When I see some Orthodox mothers and other married women in baggy “uniforms,” hunched and shapeless, I feel torturously pained. And I feel sorry for their poor husbands. It is especially hard for them now that they are surrounded by the propaganda of vice; on street advertisements, in the press, on television—half-naked beauties are everywhere… We need to intelligently stand up to all this with our own essentially different beauty. Glory be to God, lately I often see just such truly beautiful women in our church—attractive, shapely, well and tastefully dressed, but at the same time modest and decent, I hope.

– You loved mathematics from your childhood, and even intended to study in the math department of Moscow State University. A woman with a mathematical mind who also writes plays and poems is quite a rarity. Do your mathematical abilities aide your dramatic and poetic creativity?

– “In every science there is as much truth as there is math,” according to Immanuel Kant. I would add that this applies to every sphere of life. Mathematics penetrates everything; it is the skeleton of life, the frame. Math is logic. How could a playwright do without logic, without a chain of cause and effect, where one thing leads to another? It is impossible to write poems without an inner feeling of symmetry. I don’t understand what is meant by a “humanitarian mind.” Is it something deprived of a system and built upon feelings? I am sure that anyone who does not like math simply had bad math teachers. It is impossible not to love mathematics, because math is harmony. It is like nature, Mozart, Pushkin… By the way, toward the end of his life, Alexander Sergeevich Pushkin became interested in mathematics and various numerical systematizations. I read about this interest of his. If there had been good math teachers in Tsarskoe Selo,[4] then perhaps free-thinkers would not have come out of it, breeding the Decembrists and other anti-theistic movements. Mathematics is a very good stabilizer in life. All mathematicians are even-tempered, morally stable people—at least the ones I know.

– Elena, how did your parents raise you, and how do you raise your own son?

– I was raised strictly, in the soviet way. But I was raised without Christ. Therefore, we didn’t really understand why we had to be good. My child knows about Christ from infancy. He is consciously learning about Him. However, the world around us is more corrupt today than it was during my childhood. To make matters worse, my child is physically handsome. I had a more modest appearance at his age. I am afraid for him, and pray.

– What is a woman’s role in Russia’s spiritual and moral regeneration?

– Alexandra Feodorovna Romanova put it very well: “The influence of good women is the greatest power, after God’s mercy, to form good men.”

– You participated in the First All-Russia Forum of Orthodox Women. Tell us about this, please.

– To be honest, I came away with mixed impressions of that forum. The first day it was conducted in the Christ the Savior Cathedral, in the Church Council hall. There were very many people, television reporters, etc. T. A. Golikova, S. S. Zhurova, and other governmental representatives were presiding. All of them spoke some general words about mercy and virtues. But the most important issues, “juvenile court,”[5] for example, were left for the second day, which took place in the Pilgrimage Center on Lomonosov Prospect, without television cameras, and without the former presidium. Everyone was divided into four sections. In the section where I presented my report on how the mass media is corrupting us, there were thirty people—all upstanding matushkas. As a stage director, I can really feel when there is no action on the stage, but only text, because it gets boring right away. That is how it was at the forum. I immediately went on the attack when I got up to give my presentation, saying that everyone sitting there will of course agree with what I have to say. After all, we are of one mind. But it is important that those who make governmental decisions hear it. The situation in the country is catastrophic. The nation is dying out, the people are drinking themselves to death, families are breaking up, and the children’s homes are full to overflowing… Our long-time Russian values are no longer valued, everyone is obsessed with making money, and so we stupidly squander our natural resources. Industries are not developed, and science is locked up in the pen. We import everything we need in exchange for gas, oil, and coal. What good can come of it? What will we do when the resources are gone?

I am very worried about the fate of Russia. I am a patriot, and I feel my connection with my homeland in an incredibly emotional way, with my whole organism. I do not know if that is how I was raised, or if it is something inborn in me—this feeling of being part of the land, the roots, and this pain over the fate of my fatherland.

Russian people are in general a special people. I feel this very strongly when I interact with foreigners. Furthermore, what works there does not work for us. This is a particular country, with a particular culture, and a unique language which I think is the richest in the world, which arose and developed out of our national uniqueness. These are also our national resources, only they are spiritual resources, and likewise should not be sold on the market like gas, oil, and coal. They should be preserved, cultivated, and made the foundation for renewal, to the glory of God.

What I fear most of all is that calculating people who have no feeling for the country as their homeland might come and replace our current government. Glory be to God, our current government is Orthodox, and patriotic. There is hope that Russia can come out of its dead end; that it will not perish and disappear from the face of the Earth. Our main hope, of course, is in the Lord; but we the people should also act. The right words are not enough. We need action. Nothing comes without labor. That is how our world is made.

Translated by Nun Cornelia (Rees)

[1] Khodja Nasreddin is a character from Islamic Central Asian folklore that is well known to Russians thanks to the Russian language book, The Story of Khodja Nasreddin, by Leonind Soloviev.

[2] By Antoine de Saint-Exupery.

[3] A Russian word in spiritual lexicon that implies a specific spiritual labor, requiring emotional and spiritual strength.

[4] The poet Pushkin attended the university that existed in his time in Tsarskoe Selo, near St. Petersburg.

[5] The issue of a juvenile justice system is very poignant in Russia today. It refers to the laws now prevailing in Western Europe which lightly separate children from their parents for absurd reasons. For example: a family is poor—take the child to a children’s home. A mother slaps the child for misbehaving—child abuse! Take the child away. This is a system that could seriously undermine family traditions in Russia, and cause great personal tragedy.