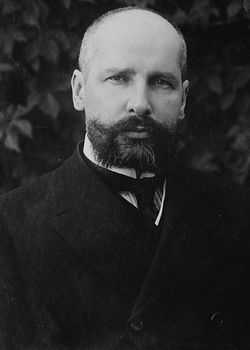

The following article from describes the service and times of Petr Stolypin, Russia’s leading statesman in the period following the Revolution of 1905 and Prime Minister and Minister of Internal Affairs from 1906 to 1911, when he died from an assassin's bullet. His hapless murderer was but a tool in the hands of "the mystery of iniquity," which doth already work (2 Thess. 2:7). Stolypin, however, will be ever remembered as a dedicated public servant, with whom not all of his colleagues agreed, but who the people loved. He embodied that nobility of soul of which, perhaps, the present world is not worthy.

* * *

In

all times, power has been a strong temptation

inciting weak souls to acquisition and corruption.

But the strong souls who rely on faith are capable of

making power a tool for pursuing good goals, and

then rulers are not a terror to good

works, but to the evil (Rom. 13.3).

The Christian understanding of power was

characteristic of Petr Stolypin, who rose to the

highest level of Russian political ranks.

Petr Arkadievich Stolypin

"It would be a great mistake to view the protection of the state from criminal acts as the state authorities' only duty, ignoring the deeper causes underlying malformations"—this is how he formulated the role of state power, setting it these two tasks: "to preserve order and take resolute measures to protect the population from revolutionary manifestations, and at the same time to strain all the energies of the state to follow the path of constructiveness, so that a stable order based on law and freedom correctly understood could once more be ensured."'[1]

Stolypin inherited a difficult legacy from his predecessors in the office of prime minister. In early August 1906, 82 Russian provinces out of 87 were in a state of emergency as revolution spread in numerous independent streams, tainted by criminal elements. The Duma did not want to discuss any of the urgent problems. Reforms had to be combined with emergency measures.

Upon entering the office of prime minister, Stolypin sent out to the governors a circular telegram saying: "The government is filled with a new intention to facilitate the legal repeal of obsolete and unworkable laws. The old order will be renewed."[2]

Stolypin set down to business with unprecedented zeal, allocating only a few hours for sleep (he went to bed at four o'clock in the morning and began his working day at nine). On the basis of Article 87 of the fundamental laws of the Russian Empire, which enabled the government to legislate during the Duma's adjournment, he managed to introduce a new legislation within five months after the dissolution of the First Duma.

On August 24, 1906, the government's program was issued, outlining radical changes in all areas of life in Russia. It was called to transform Russia into "a state without problems" within 20-30 years. Reforms were to be introduced in the army, police, central administration, regional self-government, courts, social insurance and protection of labour, land use, ethnic relations, public education, and political life. Indicated separately were plans to convene the All-Russian Local Church Council.

A renewal of life in Russia could be achieved only if there was an idea capable of rallying society torn apart as it was by the end of the century by not only group, but also class differences and professional and political controversies. The emergence of various parties, trade unions and, more important, a representative State Duma no longer allowed the autocratic power to lean on the traditional ideology of absolute monarchy. At the same time, the party discord in the Duma showed that consensus, a uniting principle of Western democracies, was unacceptable in Russian political life where even liberal parties, as they called themselves, practiced the revolutionary methods of struggle. The formal co-existence between the autocracy and the new institutions had to be replaced with organic relationships without breaking with the thousand-year-old Russian statehood.

It was not accidental that sobornost (conciliarity) came within the field of vision of Russian philosophers, politicians and statesmen at the turn of the century. European Christianity was going at that time through an acute spiritual crisis, which involved a re-interpretation of the notion of freedom, both secular and religious. The ant-like collectivism of Karl Marx, the overwhelming loneliness of the Nietzschean "superman", the sexual revelations of Sigmund Freud who saw in religion a form of neurosis—all this marked the end of an era that deified man, the age of humanism. Godless humanism is inhuman—this was the verdict that Nikolai Berdyaev passed on this paradoxical world-view: "The universal truth can only be revealed to the universal consciousness, that is, the conciliar ecclesiastical consciousness."[3] The crisis of humanism manifested itself in the numerous revolutions of the 19th century. Since the end of the 19th century, the idea of sobornost in Russia became part not only of purely theological and philosophical, but also public thought. The idea of state as a living organism whose co-subordinate structures are equal but not self-sufficient was a new step towards the authentic understanding of freedom in political philosophy.

Before Stolypin was able to implement these ideas, he had to face the proponents of a different understanding of political freedom in the Second Duma, which proved to be more Left-wing than the first. When Stolypin suggested that the Constitutional Democrats should condemn revolutionary assassinations, promising in exchange the elimination of courts martial and legalization of their party, P. Milyukov gave an evasive answer that his party's support of terror was "a matter of tactics," while the "patriarch" of the party, I. Petrunkevich, said frankly that to condemn terror meant to bring moral death to the party. The cards were revealed, but how eloquently did the Constitutional Democrats continued to speak from the Duma's rostrum about human rights and governmental terror! Even a leading member of this party, A. Izgoyev admitted that the Second Duma represented "a depressing sight of the decay of popular images."[4] The only party which supported Stolypin's program was the Union of October 17, with A. Guchkov as its leader. The dissolution of the Duma was inevitable.

In fact, the Duma refused to consider the agrarian question, freedom of religion, and many other problems. Socialists took an upper hand in it, reducing all their speeches to criticism and threats to the government. Ultimately, Stolypin had to throw into their faces his famous "I am not to be intimidated," and to abandon the idea of building a strong and efficient centre in that Duma. Increased pressure from the Right could lead to a rejection of the Manifesto of October 17, 1905, and to a ban on the Duma. Stolypin could not afford the victory of the reaction; it would mean the curtailment of all his planned reforms. In this difficult situation, he managed to observe a balance, without swaying either Right or Left. He agreed to the Duma's dissolution, while introducing a new election law to transform the Duma into a truly working legislature.

The Left-wing press immediately named these developments "the coup d'etat of June 3, 1907". This term is still wandering through the pages of Soviet textbooks on history. But the acts of June 3 did conform to the standards of the Russian imperial legislation and did not have the nature of a coup. It was essentially a new stage in the development of representative institutions. At last, Stolypin managed to find a policy conforming to Russian state principles. With the gradual re-installment of law and order in the country, the victory over mass terror, and the weakening of other revolutionary extremes, it became necessary and possible to harmonize the political system with the needs of social development.

On November 16, 1907, Stolypin came out with a declaration on historical autocracy. In fact, in his speech he developed the ideas of the outstanding statesman, M. Speransky, on Russian constitutional monarchy and autocratic legal state. Stolypin emphasized that it was only autocracy that "was called to save Russia and the historical truth during moments of upheaval and danger to the state." But the nature of autocracy, in his opinion, was constantly changing, and autocracy under Nicholas II differed from autocracy under Peter I or Catherine II, firstly in that Nicholas II granted the right of legislative initiative to some representative institutions in society. At the same time, it was the monarch alone who continued to bear the burden of responsibility for his country before God. Therefore, in some exceptional cases he had the right to breach the fundamental laws in order to save the foundations of the Russian state, because he himself granted those laws to society.

Stolypin

was far from trying to impose arbitrary rule in

public life. He insisted that such exceptions will

decrease in number in time, but until the Duma

accumulated the experience of statesmanship, and to

ensure the preservation of statehood, it was

necessary to exert "a slight pressure on

law," not to be confused with despotism, for

that "pressure" was to be exerted by a

monarch. In fact, the flow of the First and Second

Duma deputies' speeches did result in creative

legislation, while the government worked hard. At

that time, Nicholas II issued 612 legislative acts of

which only 3 were approved by the Duma.

Stolypin's opponents claimed that unless those exceptions were clearly specified, the government could manipulate its rights at will. But one has to admit that the prime minister was also right: if a state may be destroyed by a law, then who needs such a law? Good or bad, they were those "Russian state principles" which were not to be neglected by any sound politician.

The validity of the policy proposed by Stolypin was confirmed by the elections to the Third Duma, which managed at last to form a solid centre consisting of moderate liberal forces led by the Union of October 17 (the Octobrists). The elections showed that society sobered down after the bloody [1905 —OC] revolution hangover. Stolypin was pleased to note in a talk with a Volga newspaper correspondent that the new system was "a purely Russian order consistent with the historical tradition and national in spirit."[5]

Realizing that the forms of state were inseparable from their spiritual contents, he saw in the Russian Empire above all an Orthodox state. But the passion of some parts of intelligentsia for cabbala, gnosticism, theosophy and other forms of "spiritual search" and the ensuing criticism of the Orthodox Church without any understanding of its place in society and the state led to a destruction of the genuine Russian statehood.

The demand for separation of the Church from the state, understood at that time as separation of politics from morality, became a run-of-the-mill item in the program of every more or less liberal party. The bill on the freedom of religion caused hot debates in the Third Duma. Left-wing deputies tried to put the Russian Orthodox Church on the same footing with other faiths, not so much in legal terms as in the very opportunity to exert spiritual influence on the Russian people. In reply they heard Stolypin's stentorian voice: "The age-long ties of the Russian state with the Christian Church obliges it to base its law on freedom of religion on the principles of a Christian state in which the Orthodox Church as the dominant Church enjoys special respect, and special protection from the state. In safeguarding the rights and privileges of the Orthodox Church, the state is called to protect the full freedom of its initiatives that conform to the basic laws of the state. The state, while keeping within the new provisions, cannot disregard the calls of history which reminds us that in all times and in all their activities, the Russian people were inspired by Orthodoxy, which is closely associated with the glory and power of our homeland; at the same time, the rights and privileges of the Orthodox Church cannot and should not infringe upon the rights of other religions and confessions. Hence, I believe, the rejection of an ecclesial-civil legislation... would cause a breach of those age-long ties which exist between the state and the Church—the ties from which the state draws its power of spirit..."[6]

Stolypin warned against a formal understanding of the freedom of conscience: "Everywhere ... in all states, the principle of freedom of conscience yields to national spirit and popular tradition, and is implemented in strict conformity with them." When the special legislative commission suggested that the law should declare the freedom of a person to convert from Christianity to non-Christianity, Stolypin replied that the proposal should be "seriously questioned," adding: "Our people are zealous for the Church and tolerant, but tolerance does not mean indifference." He warned the deputies: "You will surely be guided by considerations of how to transform our life in keeping with new principles without damaging the vital basis of our state—the people's soul which has united millions of Russians. All of you, gentlemen, have been to our village, to our village church. You have seen how ardently our Russian people are praying... you could not but realize that the words heard in the Church were divine words. And the people seeking comfort in prayer will certainly accept the law that does not punish one for his faith, for praying according to his own rite. But the same people will not accept a law which would declare Orthodoxy, that is Christianity, equal to paganism, Judaism and Mohammedanism. Gentlemen, our task is not to adjust Orthodoxy to an abstract theory on religious liberty, but to kindle the light of the confessional freedom of conscience in our Russian Orthodox state... Remember that the law on confession of faith will work in the Russian state, and that it is to be approved by a Russian tsar who was and is and will be an Orthodox tsar for more than one hundred million people."[7]

The

Duma approved a number of bills ensuring religious

liberty, the rights to build houses of worship and

form religious communities, and the repeal of

restrictions connected with the confession of faith.

Stolypin displayed a special concern for 15 million

Old Believers, seeking to heal the wounds inflicted

on the Russian state by the centuries-old schism.

Restrictions on defrocked Orthodox clergymen

were lifted.

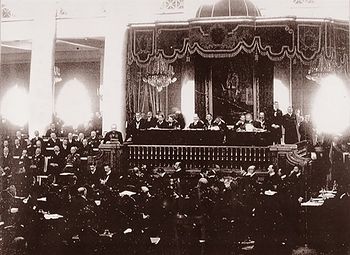

Stolypin addressing the State Duma.

The view on state system and freedom of conscience that Stolypin advocated in the Duma stemmed from the truly Christian understanding of freedom whereby there is not and cannot be political liberty without personal spiritual freedom.[8] He repeated again and again: "First the citizen, then his citizenship." According to him, a state was called to ensure the spiritual development of its citizens if it wanted to be a Christian state, for "it is only despotism, not freedom, that can do without faith."

Declaring these lofty principles of state policy, Stolypin sought to follow them in his everyday life as well. He combined the gift of a statesman with the humbleness of an ordinary parishioner. Wherever he went, he was sure to drop in the local church. He rejoiced over the well-being of parishes and helped the needy. In one of his letters to his wife, Olga Borisovna, Stolypin described his encounter with a priest at the village of Akshino where he happened to be in transit: "I inspected the church together with him, which is in good order, but the church school is awfully neglected... In view of this I promised to continue sending a five-rouble contribution for some time to help put the school in order."[9]

Stolypin's attitude to those around him was full of kindness and love. He generously shared his spiritual strength, and knew how to comfort and support people. "You wrote about your dream. It is not your soul that is not prepared for death, but those six little souls who are entrusted to your care, and your desire that they not be extinguished,"[10] was his reply to Olga Borisovna's anxious and confused letter.

Was this not the key to his personal charm?

The well-balanced policy of the government resulted in the emergence of the first signs of improvement in Russian society. From the year 1907, the pace of industrial productivity was rapidly growing, making the engineer a noted figure in society; the well-being of people was enhanced; Russian agricultural exports filled European markets. The outbursts of terrorism gradually faded away; from 1909-1910 the paramilitary organization of the Socialist Revolutionaries fell apart, and revolutionaries, one by one, started to leave "for permanent residence" abroad.

Amidst vivid manifestations of a spiritual change among the educated part of society was the publication in 1909 of a collection of studies called "Vekhi" ("mile—stones"). It marked the end of the spiritual escapism of the Russian intelligentsia and their return to the fold of the Orthodox Church and the state. These developments were highly appraised by Stolypin, who closely followed the public effect of his reforms. He called Vekhi "one of the first spiritual fruits of those rudiments of freedom which began to develop little by little in Russian life." The Orthodox faith proved to be that fertile soil on which grew the religio-philosophical ideas of the thinkers who augured the philosophical renaissance of the 20th century.

The fact that the Third Duma approved his agrarian reform, the corner stone of his internal policy, was another important victory for Stolypin. Advocating his view of land use by peasants, he said: "The Government wishes to raise peasant land ownership to a new level; it wants to see the peasant rich and well-off, because where there is wealth, there is enlightenment and true freedom... But to this end, it is necessary to give an able and industrious peasant— the salt of the Russian land—the opportunity to be free of the grip of life conditions that currently hold him back. He should be given an opportunity to keep the fruits of his own work for himself, and to make them his indelible property. There was a moment not long ago when faith in the future of Russia was shaken; what was not shaken at that moment, though, was the faith of the Tsar in the power of the Russian ploughman and the Russian peasant!"[11]

The

Decree of November 9, 1906, allowing the peasant to

leave his community to become an individual and

hereditary owner of land was a great success. Some 13

per cent of the community lands were transferred to

the individual property of peasants. On the eve of

the revolution, Russia was about to become a nation

of landowners who could rapidly get rich. In

Stolypin's time, Siberia, a place of resettlement for

the land-starved peasantry, began for the first time

in history to export agricultural products such as

grain, butter and eggs. On the eve of the February

revolution, the peasantry owned or rented 100 per

cent of the cultivated land in the Asian part of

Russia, and 90 per cent in the European part.

Peasant homesteaders present Stolypin with traditional bread and salt near Moscow. 1910.

The economic base for revolutionary disturbances in the country was liquidated. Why then were peasants so responsive to the slogans of the Socialist Revolutionaries and the Bolsheviks in 1917? Historians will have to study the question. But we can point to some socio-psychological and moral aspects of the reform.

Some myths which took root in people's minds were created through the efforts of revolutionary propaganda. Among them were agrarian theories of that time, based on the groundless premise of the domination of landed estates in the country, and an alleged land-hunger among peasants. Their authors deliberately distorted facts that actually indicated a real decrease in landed estates and an increase in peasant land ownership (by 1918, the ratio of the land possessed by the gentry to the land possessed by the peasantry was 1 acre to 5.5 acres against 2 acres in 1894). The Russian "land-starved" peasant who possessed from 1 to 5 acres could have been envied by any peasant in Germany or Denmark.[12]

The myths rooted in people's psychology presented a more difficult problem. They included above all the traditions of communal land use, which Stolypin was so resolute to break. He emphasized the strictly voluntary principle of peasants leaving the community, but this principle was faced with a time factor. The threatening events of 1905-1907 forced him to make haste, which in a number of cases led to administrative abuses in provinces and peasants' forced withdrawal from their communities. Communities were obliged to make a redistribution of land at the request of even one person. Then the size of all other strips of land had to be reconsidered, which made it impossible for the community members to run their farms in peace. The hatred that community peasants felt for individual peasants was fed by mere envy, which led to cases of arson against individual farms, and mutual dislike between the two groups of the peasantry.

Yet the principal reason for curtailing the reform by the summer of 1917 might have been the seemingly winning slogan of support for a "strong peasant." This declaration ran contrary to the peasants' age-old idea of the tsar as protector of the weak, and undermined the idea of monarchy at its root. If in the past great Russia was built through protecting the weak, now it was to be built through the rights of the strong. This did not tally with that "truth for all," of which the peasantry dreamt. Interestingly, Leo Tolstoy, in his personal correspondence with Stolypin, pointed to this moral defect of his reform.[13]

The economic validity of the Stolypin agrarian reform is evident today. But at that time, it encountered the enduringly strong tendencies in people's psychology. When the long-awaited Decree on Land was issued in 1917, most peasants behaved like those lean cows in Pharaoh's dream, which ate up the fat ones, but looked just as lean and ill-favored as before (Gen. 41.17-21). The public consciousness was revolutionized in a paradoxical way: the revolution caught Russian society on its way from worse to better, when some people believed that the reform was going too slow. Woe befell the people who yielded to that temptation!

The year 1909 became a time of both ups and downs in Stolypin's reform. Having coped with revolutionary upheavals, he now faced a growing reaction from influential Right-wing members of the State Council, such as V. Trepov and P. Durnovo, and the Union of the Russian People, who accused him of dangerous liberalism and flirting with the Duma.

Stolypin's struggle with political intrigues and his selfless protection of the royal family's authority against unseemly encroachment and all kinds of adventurers cost him dear. According to A. Pilenko of the Novoye Vremya periodical, Stolypin said to a foreign ambassador in 1910: "My authority has been undermined; I will be supported as long as my power is needed, and then I will be thrown overboard" (Moscow Weekly, March 20, 1910). Stolypin, an "honest sentry," proved to be an obstacle here as well by rejecting to resign with his precious goal achieved. The situation in the country had stabilized; the rebellious peasant was replaced by Stolypin's "strong peasant" who attacked the landed estates not by onslaught, but by more successful economic siege. Stolypin's auditing commissions, aimed at high-ranking thieves and bribetakers, along with the Duma's inquiries, threatened to cut off many officials from the feeding trough of power. The Right and Left were shaking hands over his head, and nobody could be sure as to which side would strike a mortal blow.

Stolypin encountered great resistance from the State Council in 1911, when the bill on the introduction of country-states in western provinces was discussed. His version of the law ensuring a Russian majority over the Poles at elections (the latter comprised 2–3 per cent of the population of those provinces) was easily adopted by the Duma, but rejected by the State Council. The results of the vote in the State Council shocked Stolypin, who attached great importance to the law, which he hoped would serve as a prototype for new state and national relations that would be Russian in spirit and multinational in form. For the first time, Stolypin could not restrain himself; he left the Council immediately and handed in his resignation.

An acute governmental crisis broke out, which lasted for over a week. Stolypin was forsaken by all; the Right and the Left alike openly expressed their delight; some ministers hastened to come over to the minister of finance V. Kokovtsev, who was rumored to be the next prime minister. A. Guchkov, the leader of the Octobrists and Stolypin's ally, left for the Far East as a sign of protest. For the first time, the reformer felt an absolute vacuum around him.

A year and a half later, in his speech in memory of Stolypin, Guchkov would say, "Stolypin was a sincere and committed proponent of popular representation," which he protected from every threatening menace coming from the Right and the Left.[14] But that appreciation would only come later; in the meantime the Left-wing press was scoffing at the former prime minister. "Look, what a delight, what a carnival mood," wrote M. Menshikov in Novoye Vremya on March 10. The cause of the prime minister's resignation was sought in the current governmental discord, in his own faint-heartedness, his ambitions, and political tricks. Amid all this noise in the press, the sober, accusing, but well-wishing voice of Menshikov sounded in a genuine attempt to analyze what had happened: "Indeed, if every kind of service, including public service, is looked upon from the point of view of personal gain, then why should one not give it up, if it becomes too hard physically and morally? But what is proper for a petty philistine is inadmissible for representatives of a higher estate... A resignation is admissible if you are sacked or if your illness or old age make you handicapped. But to leave at your own will in your prime, whether you like it or not, looks like you have not fulfilled your duty to the end... What would happen to a warrior, even an ordinary soldier, if he should ask to resign during the heat of a battle?"[15]

And the warrior returned to the battle-field.

Grand Princes Alexander and Nicholas appealed to Empress Aleksandra Fyodorovna for help. They pointed at the Left's delight, indicating that the seditious forces were lifting up their head, and that only Stolypin could cope with terrorism and conspiracies. The Empress had an unpleasant talk with the Tsar, after which Nicholas II agreed to hear Stolypin's terms. Stolypin's demands looked more like an ultimatum: to dissolve the Duma and the State Council and, in the meantime, to introduce the law on western country-states on the basis of Article 87; to send V. Trepov and P. Durnovo, Stolypin's relentless opponents in the State Council, on leave until January 1.

Both conditions presupposed an unprecedented scandal and put the Tsar in a very difficult position.

Nevertheless, he accepted them, and Stolypin was given powers to act at his own discretion. It was an unheard-of triumph, for he prevailed on all points (the law on western country-states was adopted unhindered only after Stolypin's death, which means that in the spring of 1911 it was not passed for political reasons).

Even the allies of the prime minister, the Octobrists, could not stand such a blow at fundamental law. The Duma and the State Council deemed Stolypin's actions to be illegitimate and his explanations inadequate. The Duma was then dissolved once and for all.

Public opinion called Stolypin a "dictator." An ominous rumor spread all over St. Petersburg that the Tsar did not forgive the prime minister the pressure he brought to bear on His Majesty's will, and was thinking about another assignment for him.

The epoch of great reforms had reached its zenith and now was inexorably sliding into a decline. All the energies of the reformer had been given to his homeland. Now what remained to be given was his life.