Faraway Athos, I will never see you: your mysterious mountains and austere monasteries, secluded kellis and kalyvias, rocky trails to Karoulia and the peaks of Katounakia; I will never descend to the blue waves of the Aegean Sea, will never awaken to the sound of the wooden tuaka in the pilgrim’s quarters—arxontariki. It’s a special place—people are not born there—they live, pray, and die there to enter into the Heavenly Kingdom. Although they live in the body, the monastic life is the angelic life. And Athos itself is much closer to Heaven than to Earth.

The monastic republic of Athos is inaccessible for women. But I can listen to stories about Athos from my first spiritual guide—Igumen Savvaty.

Trapeza has ended in the monastery, the thanksgiving prayers are read. The sisters sit again and wait with bated breath. Fr. Savvaty attentively examines his spiritual children:

“Well then, ask…”

He listens to numerous questions and answers them. Then he tells us about Mt. Athos:

“As you know, I was on Athos seven times, and lived and worked there for a few weeks each time. What is Athos for me? It’s hard to answer succinctly… Athos is a spiritual school, a rigorous school… I wouldn’t be able to live there long: That’s not my measure of asceticism. I am spiritually weak… To live on Athos is all asceticism. Athos is no resort; Athos is a hospital.

Everything falls into place there. You get such a spiritual jolt there! You lose your pompousness and feel like a stranger to God. Athos sobers a man, and you understand how you should live, and what you should do.”

Fr. Savvaty smiles:

“Before, when I was a spiritual baby, I would go to regular monasteries, to holy places… Now I am grown a little—twenty-five years as a priest—I’ve started first grade in spiritual school… I got tired of porridge and began seeking for solid food. And on Athos they eat this solid food…

For whom is it helpful to go to Athos? For priests and monks firstly… To receive a spiritual recharge for their pastoral activities. And it’s good for the laity too. It’s useful for whomever the Mother of God opens the path … If it’s not the will of the Most Holy Theotokos, then even the president can’t fly there.

And some simple village priest, maybe having straw in his beard from having worked all day without a break, and still managing to mow the hay for his cow, in some old cassock prays to the Heavenly Queen, ‘Most Holy Theotokos, help me to get to Athos!’ And you’ll see—within a month he’s on Athos!

Therefore, when people ask me what they have to do to get to Athos, I answer, ‘Pray to the Most Holy Theotokos.’”

The first night on Athos

I first went to Athos in 2000, and I was at that time somehow confused by the thought that I am a spiritual father and builder of a woman’s monastery. Although the monastery was built at the blessing of my spiritual father, Archimandrite John Krestiankin, although its foundation was foretold by Elder Archpriest Nikolai Ragozin, still I was tormented by the thoughts, “What I am doing here on Mitena Mountain? Is this my place? Maybe I should chuck everything: this women’s monastery, the sisters, all those babushkas—and leave for Athos? To labor ascetically there… Or just to go to a men’s monastery?”

And in my first night on Athos, I was standing in church, at three in the morning. I didn’t manage to take a nap in the evening; I was going on more than a day without sleep… There was no electricity in the church, candles were burning, prayers were being read. It was stuffy, my head was spinning, and I went to the narthex and sat on a bench. It was fresher there, with cool air coming in from outside, and the sound of the service reached us from the church. I closed my eyes and began to pray.

Suddenly I heard the shuffling of the feet of an old schema-monk, all bent over. He came closer, sat in the corner in the narthex on a stone seat, his face not visible, only his white beard and bright face, glowing in the darkness. He crossed himself and quietly asked, “Who are you?”

“A hieromonk,” I answered.

“Where do you serve, and for how long?”

“In a women’s monastery, for thirty years.”

He asked so domineeringly, as one having authority, and I was breathless. I realized that on this first night on Athos, I was hearing what I had prayed so long about before my trip: that the Lord and the Most Pure Theotokos would reveal to me His will for my future path.

The schemamonk spoke as if he knew about my embarrassing thoughts, about how I wanted to leave the women’s monastery. He spoke briefly and extremely simply: “There, where you live—there live. Don’t go anywhere. You should die there. Carry your cross to the end, and be saved.”

He silently stood up and slowly left, like an old man, shuffling his feet, and I sat and thought that I hadn’t even asked him anything; I hadn’t tried to start a conversation. That’s how, on my very first day on Mt. Athos, the Lord revealed His will to me.

Athonite elders

Yes… There on Athos, such elders are laboring… There are some whom not a single living soul knows about… In the kontakion of the service for the Athonite saints and ascetics of the Holy Mountain it says, “Having shone forth therein an angelic life…”

They told me about a group of Russian priests who visited Athos in the seventies. They stayed at St. Panteleimon’s Monastery. They went for a walk around the area, and stumbled upon an abandoned skete. They decided to serve Liturgy there the next day, asked the Athonite brothers about the skete, and received the answer that no one had lived or served there for a long time.

They began the Liturgy, and during the service they saw, crawling into the church, an ancient old monk—so old that he was unable to walk for a long time already, only to crawl and somehow move. Even the oldest monks of St. Paneteleimon’s didn’t know about him. Apparently, he was one of the pre-revolutionary monks. He was crawling, and said, barely audibly, “The Mother of God has not deceived me: She promised that I would commune before my death.”

We communed him, and he died right there in the church. How did he live? What did he eat? He communed, and departed to God and the Most Holy Theotokos, to Whom he had prayed his entire life.

On foot around Athos

After my first trip to Athos and the meeting with the Athonite elder, my confusing thoughts about moving to another monastery, or moving to Athos, left me. A few years passed… It was such a peaceful time in the monastery. But, generally, complete peace never happens in the monastic life. If you are correctly laboring in asceticism, waging spiritual warfare, then sorrows and temptations are your inescapable companions in this battle.

A whole series of heavy temptations, both internal and external, began with us. The main weapon in spiritual battle is prayer. Of course the whole monastery was praying. But, apparently, our weak strength in prayer was not enough, and we needed spiritual help and support, and they blessed me to pray at the Athonite holy places—there, where Heaven is closer to Earth, where continuous prayer is offered up for the whole world.

Earlier people, offering up their prayers to God, would make some kind of a vow: to visit the holy places, some famous monastery. They usually went on foot to offer their labors to the Lord. I also wanted to append some kind of labor to my prayers about our monastery—some kind of sacrifice—and when I asked a blessing for such a labor, they blessed me to prayerfully walk on foot around Athos, and to venerate the sacred objects, to pray and ask for help in every monastery.

Frightful Karoulia

And when I was walking around Athos, I visited Karoulia.

February: At home, in the Urals, snow is lying, a blizzard is swirling, and here, on Athos, its 65 degrees, they’re planting potatoes and onions…

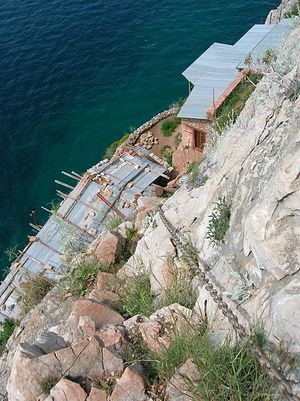

“Karoulia”—a pulley, a lifting device with which hermit monks, not descending down the cliffs, could barter with the fisherman passing by: fish, rusks, and olives in exchange for their handicrafts. Karoulia is located in the southernmost part of the Athonite peninsula, not far from Katounakia.

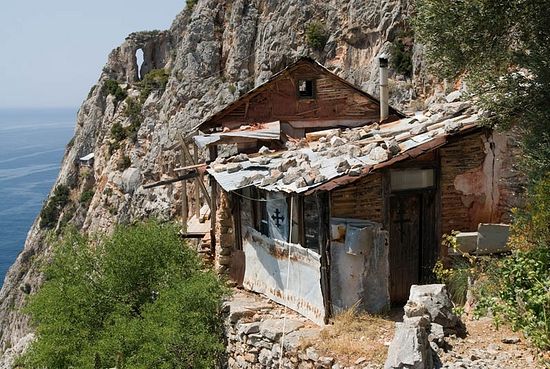

Karoulia is inaccessible cliffs, narrow trails, empty cells, formerly the shelters of eremitic monks. There are swallows’ nests on the cliffs, and the homes of hermits, attached to the cliffs like birds’ nests. There is Outer Karoulia and Inner Karoulia, or Frightful Karoulia, so called because the monks’ cells are directly in the cliffs, and to climb there, and generally to move around, holding onto the chains and wires, is dangerous and simply frightful.

The ferry from Daphne reached the final stop at Karoulia, and I got out alone onto the concrete pier. The path from the pier climbs up the mountain by stone steps, and, ascending, I discovered the remains of a small chapel and a burnt-out cell where the renowned Karoulian schema-archimandrite Stephen the Serbian lived. Nearby was the cave in which, as I knew, Archimandrite Sophrony Sakharov, a spiritual son of the Athonite elder Silouan, had once labored.

Not far from the burnt cell there lived some Russians: Hieromonk Iliya and a lay monk. We met. They had lived there for two years and had managed to catch Fr. Stephen among the living. I had read about him earlier, and now I was hearing about him from people who had known him personally.

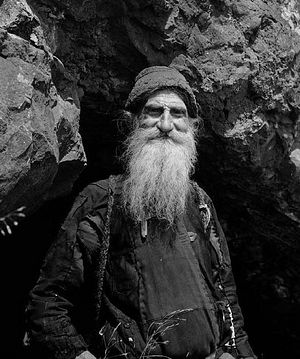

Fr. Stephen

A Serb by birth, he was an anti-fascist during World War II, and participated in the resistance. He told about how he was arrested with other resistance fighters and was led out to the firing squad. Fr. Stephen gave a vow to the Mother of God, that if he remained alive, he would go become a monk on Athos. When they began shooting, something as if pushed him, and he ran. He felt like bullets were burning his back, hands, cheeks, but not inflicting any harm. And the Germans didn’t chase after him, which was also a miracle.

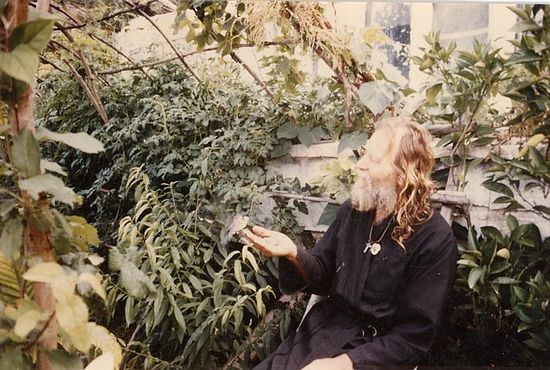

After the war he received the monastic tonsure on Mt. Athos and labored there ascetically just under fifty years. He knew a few foreign languages, and wrote spiritual articles and directions. Fr. Iliya saw how the elder labored on the terrace, and the snow-white doves would fly up and sit on his shoulders, and when he would stop writing, the doves would fly away.

Once a friend from Russia visited Fr. Iliya, and he took him to Fr. Stephen for a blessing. The nearly eighty-year-old elder had blue eyes, like the sky; he did not wash himself for many years according to the tradition of Athonite monks, but there was no smell. He ate little, preferring xerophagy1: He always had dry vermicelli in his pockets, which he himself ate and which he also fed to the birds.

On Annunciation he would lower a net into the sea and ask, “Mother of God, send me fish.” He would immediately pull it up, and there were always fish in the net.

When he would fix his dilapidated cell, a friend would bring him building materials. This friend had a five-year-old daughter, Despina. When the elder was in need of the friend’s help, he would go out to the sea and loudly ask, “Despina, tell your father to come here; I need him!” And the girl would run to her father: “Papa, Fr. Stephen is calling you.” Why didn’t he turn to his friend directly with this request? Maybe the girl, with her purity, could better hear the spiritual calling; who knows… And when the friend would arrive, he would ask, “Fr. Stephen, did you really call me?” And the elder would answer, “Yes, I asked Despina to tell you I was waiting for you.”

Recently he had been somewhat of a Fool-for-Christ, covering his spiritual gifts with foolishness. If Russians came, Fr. Stephen would sing “Moscow Nights.” And when they came, he sang them the song, then put a kettle on the fire to treat them with tea. Fr. Iliya’s friend looked at the hermit with disbelief: some old man, singing songs—and this is a great elder of prayer?!

But the kettle was old and black with soot, without a handle, just the body. And when the water in the kettle reached a boil, Fr. Stephen grabbed it directly from the fire with both hands and started pouring it into the teacups. Both guests looked in terror: The kettle was glowing, but the elder calmly poured the tea, and didn’t get any burns from it.

Fr. Iliya said that when America bombed Serbia, the elder fervently prayed and offered his spiritual contribution to protecting his homeland through prayer. And he was so anguished that he experienced severe spiritual sufferings. At that time his cell also burned down. Was there a spiritual reason? We can only guess. But when he moved to the cave, he continued to pray for his compatriots killed in the flames of the explosions, and his cave started to burn.

Fr. Stephen died in Serbia. Before his death he returned to his homeland, to the monastery where the abbess was his relative, and he reposed on the feast of the Entrance of the Most Holy Theotokos into the Temple. And she, to whom he had prayed so many years, received his soul.

A stone from the cave

Fr. Stephen’s burnt cell was adjoined to the cave where Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov) had once lived. When I went to Athos, one nun, greatly revering Elder Silouan and Fr. Sophrony, asked me to bring her at least a stone from the cave. I didn’t know where this cave was located. For me, her request was tantamount to asking me for a stone from Mars. But then I went to this precise cave. There was water trickling there. I picked up a stone and realized I had just fulfilled the nun’s request.

A hospitable welcome

The hieromonk, Fr. Iliya, invited me to spend the night in their dwelling. They gave me a place right by the entrance and offered me an old blanket and even an old ragged pillow.

I was very tired and was glad for such a hospitable welcome. Night was approaching, and having prayed, we started to get ready for bed. I lay down with my feet into the cave and my head towards the entrance so I could see the starry sky. I was lying there and thinking about how such a romantic night reminded me of childhood hikes in the forest. But I soon began to realize that childhood hikes and Athos nights have nothing in common. I had heard so much about Athonite terrors, and here, on Karoulia, I was experiencing them myself.

A storm began that night—a tempest, winds. From above, from the cliffs, pebbles were falling down, sticks, splinters, and the sea was raging. I really wanted to sleep; I couldn’t solidly fall asleep but felt half-unconscious: I felt like the spray of the waves was pouring on my head, and shoulders, and I pulled the blanket over my head, half-asleep.

And nightmares were piling on: In my half-unconscious state it seemed to me that the monks were conspiring against me, that they were going to kill me, and throw me over the cliff. I tried with all my strength to wake up, and I realized that it was just a bad dream, but my consciousness again drifted off, and my enemies were pursuing me again. Through sleep I heard one of the monks pass by to the exit of the cave and go back again, and the fears again piled on. It was a conspiracy against me. I was trembling all over from fear and felt like my teeth were knocking.

The nightmarish delirium, tormenting me all night, melted away with the morning sun. The storm subsided, and all fears departed. It turns out that the monk who was leaving the cave all night had a toothache, couldn’t sleep, and was wandering through the cave. In the morning he went to the hospital.

The second monk offered to guide me a bit.

Along the way he told me how four pilgrims came, having decided to walk all the way to Inner Karoulia. They spent the night, like me, in the cave. One of them talked the whole night about how he’s a mountain climber, and the path ahead didn’t scare him at all: He would go over it himself and guide his friends. But the next morning, when they came to the slope down to the trail leading to Inner Karoulia, the climber’s determination left him, and he flatly refused to continue the path. He and his friends turned back. Apparently, the reason for his fear was more spiritual than physical, although, in fact, the slope could scare even the valiant.

Inner Karoulia

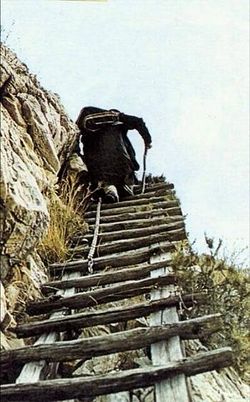

We reached the place where you could get down onto the trail by the chains. Outer Karoulia had ended. The stony path ended at the very top of the red cliffs, running steeply down, to the sea. My guide said goodbye and turned back. I was left alone. The chain continued downwards, the end of which was not visible due to the roughness of the cliff. It was unclear how much time was needed to descend along that old chain, clinging to the rocks heated by the sun. I prayed and got on this Karoulian homemade ladder.

The ladder was rotted; one step was there, and the next not. Climbing down, I looked below and my boot fumbled on small protuberances, polished by the feet of the Karoulians. The abyss opened before my eyes, my heart pounded, beating unevenly, and my mouth dried out: One wrong move, and I would fall below. I knew that there, below the cliffs, was a bottomless pit, nearly an abyss. I had read earlier that the depth of this abyss is a whole kilometer. Legends tell of this cavity: of a terrible sea octopus, of sea fish-beasts with terrible jaws that inhabit the uncharted depths of the Singitikos Gulf by the Karoulia crags.

I began to pray aloud and free myself from thoughts of sea monsters. The descent, to my great joy, turned out to be not very long—thirty meters. And then I was standing on the path leading to Inner Karoulia. I recovered my breath. The path followed a small ledge along the cliff, so narrow, a fifty-centimeter terrace. I could barely even stand on it with both feet. I was covered in red dust from the rocks, my hands and knees shaking. By the end of the journey they would be covered in blood.

If you walk along the path, you will meet dark openings leading into caves. Athonite hermits once labored here. Now Inner Karoulia is deserted. Modern monks cannot bear the ascetic feats of these previous inhabitants, as spiritual children are unable to bear the labors of those well-seasoned in spiritual battles in the wilderness.

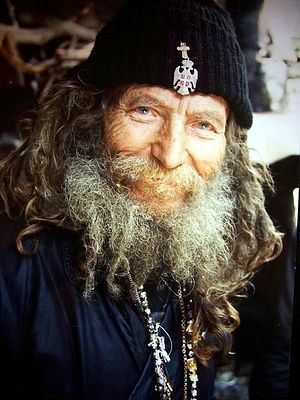

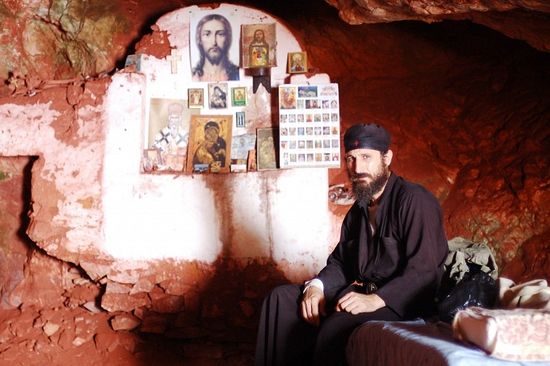

Although, those who want to test their spiritual strength and to take upon themselves the life of the Karoulia hermits do come here from time to time. I met one such modern inhabitant of Inner Karoulia. He was also a Russian, introducing himself as Novice Sergei. He had settled in one of the caves and was glad to meet a fellow Russian, although he said almost nothing about himself.

I wasn’t trying to question him: A person who has come here to pray in solitude obviously is in no need of company. People come to Karoulia for special prayer, for repentance, and sometimes by a vow. I was already warned that certainly not everyone could get to Inner Karoulia: only he who was blessed by the Most Holy Theotokos.

Therefore, we didn’t have a long conversation, although Sergei hospitably offered me food. There on the ledge of the cliff he made some pasta and tea. I shared with him my anxieties and worries about my home monastery and told him about my blessing to walk around Athos in prayer.

I felt a surge of strength after eating, and, sitting on the edge of the cliff, I began to cheerfully look around. The thought came to me that this Frightful Karoulia is not so frightful, that I could live and pray here. It was a proud thought, and apparently, because I did not banish it at once, a momentary temptation followed. On Athos in general spiritual causes and effects are very short in time.

The Lord deigned to show me what dangers the Karoulia hermits meet: I felt like some kind of force began to move me towards the brink. There was about a meter to the abyss, and terror seized me: This unkind force would sweep me over the side like dust. I dug my boots into the trail, but my movement towards the precipice continued: It is impossible to resist spiritual temptation by physical strength.

I began to loudly say the Jesus Prayer and only then felt the pressure ease, and gradually stop. The novice, who was not far away, occupied with his own business, hearing my prayer, asked nothing, nodding his head understandingly. Apparently he was acquainted with such temptations.

And I understood that not just anyone could live and pray in Frightful Karoulia, but only those ascetics who had acquired humility. The Lord and the Most Holy Theotokos allowed me to come here, protecting and preserving me, as a spiritual babe. And when the babe accepted a proud thought, they allowed him to see this journey in the true light.

As dusk drew near, I said goodbye to Sergei, who within a matter of hours had become like family—it is a property of Athos to bring people together. I needed time to get back to Outer Karoulia before dark. My legs gave way when I reached the cave of the monks where I had left my backpack and all my things. They greeted me joyfully.

St. Anne’s Skete

I said goodbye to the monks, and, going higher up the mountain, found the path to St. Anne’s Skete. To the right of the path was the mountain, and to the left—a steep slope, nearly a cliff, and thorn bushes. Recalling the path to Inner Karoulia, I relaxed. In comparison, this was easy. I was daydreaming, admiring the greenery, and I forgot about prayer, and I nearly paid for it: I stumbled on a rock and barely kept from falling over the edge into the thorn bushes. Only my staff saved me: It’s typical to maneuver about the Athonite paths with a walking stick. I gathered myself and went further, with prayer, as is necessary when walking around Athos.

In the skete they have the relic of the foot of the holy and righteous Anna in a silver reliquary. Venerating it with prayer, I felt such love, such comfort and heartfelt affection that I wanted to do something for the mother of the Most Holy Theotokos after returning to my home monastery—to offer her some kind of gift. A few years later this desire came true: A skete named for the holy and righteous Anne grew up next to our monastery, and even a small particle of her relics appeared in our skete. She herself came to us through benefactors. The services and the whole daily routine in the skete are according to the Athonite rule. Thus, a piece of Athos is with us now, in our Ural monastery.

A hermit’s cell

The first time I went to Mt. Athos, I dreamed of finding the cell of some elder-hermit and speaking with him. I understood that this dream was somewhat childish…

And then once when I was staying at the Russian monastery of St. Panteleimon, I decided to go for a walk around the area in my free time. I started walking in the direction of Daphne, and going away from the monastery a bit, to the left of the road I found a small path, nearly overgrown with bushes. I even wondered if it was a human or a boar’s path. Then I decided to try to go along it. The path steeply rose up the mountain, enticing me forward. I would lose it and then find it again. At some point it turned into rocks, and I was certain it was a human path: The worn steps became visible, laid by the hands of its owner.

Then a clearing opened up before me with a heavily overgrown olive orchard. My heart began to pound: Perhaps I’m going to meet a hermit-elder? I went deep into the orchard and saw a tiny cell with one window two meters long, and a meter-and-a-half wide. On the door was painted a faded Russian inscription: “This cell belongs to Hieromonk…” and then I couldn’t make it out—it had totally faded.

I walked around the cell, listened, and understood that no one had lived here for a long time. I said a prayer and opened the door. Dilapidated walls, a window, a wooden bed made of boards, several icons in the corner—that was all the furnishings of the hermit’s cell. How did he live here alone? How did he labor? A man of prayer… I didn’t even have to meet him, but I knew this cell had an owner who lived and prayed here, and I wanted to honor his memory, and to honor the guardian angel of this cell.

I took my icons out of my bag and began to read an Akathist to the Great Martyr Panteleimon. A feeling of compunction came to me. I read until the end, and only then as if returned to reality. I realized that the sun had already set. Darkness comes quite sharply on Athos, and the nights are very dark. I managed to get back, with difficulty, barely making out the trail, and heading towards the road. I was praying aloud—I was afraid of getting lost. I had just gotten onto the road from the trail when complete darkness fell.

I realized it was not the car road from which I had turned onto the trail during the day, but it was also a trail, although well-trodden. Little trails came off of it, which I felt almost by touch. I walked with difficulty, experiencing great fear. Most likely it was a spiritual fear—fear on Athos is business as usual. These places were a little dark in the daytime due to the thicket, but now I stumbled with every step on rocks, which I couldn’t even see under my feet.

I begged the Great Martyr Panteleimon for help, and immediately after my prayer I abruptly came to the church of St. Mitrophan of Voronezh in St. Panteleimon’s Monastery.

The next year I found myself at these places again with a friend, a hieromonk. I told him about the hermit’s cell and we decided to go there. We found the overgrown trail, and the clearing with the orchard. It was all somehow miraculous: The air was full of freshness and the smell of honey from the wild yellow daffodils. On Athos you often experience the feeling of spiritual tenderness. But sometimes it’s even frightening to step on the rocks: The feet of the Most Holy Theotokos herself have stepped here.

With trepidation we opened the door of the cell, went in, and I immediately realized that someone had visited here the in the past year, and this guest had been hosted here for some time: The traces of his stay were shown by several glossy erotic magazines. I felt serious anger, as if before my eyes this holy place was defiled, where some hermit-ascetic had prayed to God. At the same time, my friend and I felt quite embarrassed, and we turned away from one another, hiding our eyes. Perhaps Ham’s brothers had experienced the same feeling?

Then, without saying a word, we found an old rusty bucket and burned the magazines. They didn’t want to burn because the paper was thick. We tore the magazines apart and burned them to ashes. I immediately felt relieved, as if the cell had been cleansed. We prayed, and silently went back. I walked and I thought: The whole world is filled with filth, and now it has penetrated even onto Mt. Athos. O God, have mercy upon us, sinners!

And again after a year I found myself in those parts. I persistently tried to find the trail to the hermit’s cell, but I was unable: The road there was completely closed.