Did you know that in old Russia convents for many centuries were located within the walls of monasteries for men? There were almost no separate convents. Of course, communities for nuns lived separately, but on the territories of monasteries for men, enclosed by walls. This practice existed in both the Byzantine Empire and Russia (Rus’), and the most glorious monastery of Kiev (also Kyiv) was no exception. So, we offer a brief history of the convent at the Kiev Caves Lavra to all lovers of Kiev antiquity.

At war is like at War[1]

The major reason for the common community life of monks and nuns (which today would seem odd and full of temptations) was the permanent threat of war. Most ancient and medieval monasteries were situated outside fortified cities—fortresses of that time had very limited space. In addition, monasteries’ livelihoods chiefly depended on their lands, so it was more convenient for monks to settle near their farms instead of travelling there from cities. Besides, for many, withdrawing from the world automatically meant living outside densely populated places.

And now imagine a separated and isolated nunnery in the atmosphere of constant raids by the Polovetsians and Tatars, Persians and Arabs, the heterodox and non-Christians, and numerous bands of thieves. It is obvious that without building a good fortress, without quartering a military garrison, the life of a convent like this would not have lasted long and would have ended in tragedy. And if nuns were to elect permanent guards, then monastery brethren were the best candidates. Thus many early monasteries in the regions with continuous danger of war became “double”, or “male-female” monastic communities. And, in fact, they remained such until any threat of war was removed in the nearest regions.

Another reason for the presence of communities of nuns within monasteries for men was the need of clergy—a (male) priest is a symbol of Christ, and this is why women cannot be ordained priests. In cities the situation would have been easier: priests could regularly visit convents for performing services and sacraments. But what about nunneries, situated far away from cities (taking into account extremely long journeys in that era)? It is not very good for a priest or two priests to live in an isolated community of nuns on a permanent basis. Making occasional visits to convents is not ideal either. Finally, sisters valued the possibility of choosing confessors from among ten experienced priests or more, and monasteries for men with a large number of priests on the same territory provided them this opportunity.

Many tried to combat this “violation” forced by circumstances. Thus, the Byzantine Emperor St. Justinian (ruled 527-565) issued two decrees forbidding the establishment of double monasteries. However, the war danger was so great that these decrees were not observed in practice.

In Western Europe, after the introduction of Roman Catholicism, the similar laws became part of the reforms of Pope Gregory VII Hildebrand (1073-1085). Despite this, some double Catholic monasteries existed in Western Europe for some 200 years after that. As long as there were inner “wars with heretics”, as long as there was a danger of invasion of Western lands by Turks, Tatars and Moors, it was not safe for female communities within double monasteries in the most dangerous regions to separate and become independent.

A similar situation (but even with a higher level of danger) existed in what is now Ukraine in the thirteenth to seventeenth centuries, which caused the establishment of a great many double monasteries. There were as many as four such monasteries near Kiev alone. Monasteries with both male and female communities had probably existed in ancient Rus’ earlier.

Why “the Maidens’” Convent?

The Kiev Caves Lavra was also formerly a monastery for males and females. The earliest official written record of nuns, eldresses and an abbess at the Monastery of the Caves dates back to 1159. However, it is a faked document, forged either in the sixteenth or seventeenth century by the authors of The Charter of Andrei Bogoliubsky.

The earliest reliable date is some time in the 1540s. The will of one schema-nun of the Maidens’ Convent of the Caves that dates back to that decade transferred the ownership of her estate to the Lavra. On the basis of this and many other documents of that period it can be concluded that representatives of upper classes—among the gentry, and even princesses—joined the female community of the Caves. Another testimony is the fact that in all the seventeenth-century documents the Convent of the Caves was called “the maidens’ convent”, or “the convent for unmarried noblewomen”, not merely “the convent for women” as was the case with the majority of other convents.

Firstly, until the end of the nineteenth century the word “zhenshchina” [today meaning “a woman”, “a lady” in Russian (as the word “zona” in Polish) was used for a female commoner, as opposed to a representative of high social class; whereas the Russian word “devitsa” [today meaning “a girl”, “an unmarried young woman”, “a virgin”] (as opposed to the vulgar popular term “devushka”, which today means “a very young woman” or “a young woman”) and the Polish word “Panienka” then were used for unmarried representatives of the elite. By the way, representatives of the nobility and boyars [members of the old aristocracy in Russia, next in rank to a prince—Trans.] originally lived at “maidens’” and “new maidens’ convents” in Moscow and other cities of Russia as well.

Secondly, until the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the decision to enter a convent was not usually left up to young women or even widows from among the common folk. However, in the late medieval period the term “zhensky monastyr” [that is, “a convent for female commoners”] finally appeared, albeit they were situated somewhere at the back of beyond. Alas, the secular social stratification affected even such things as withdrawal from the world.

In the language of documents: The convent’s beginning

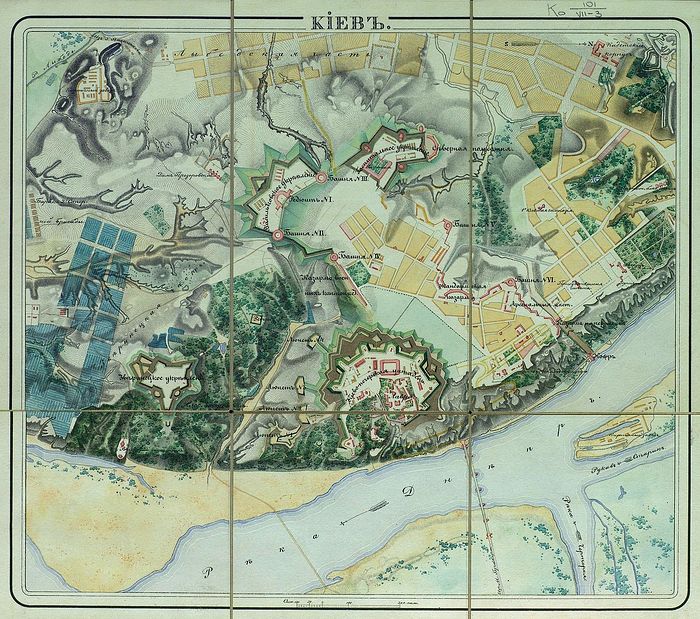

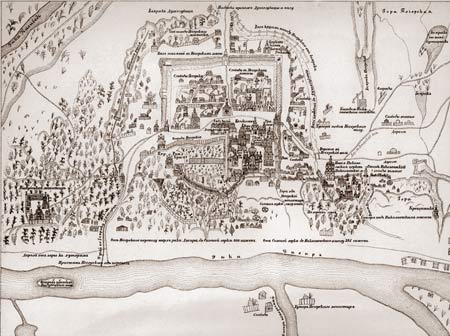

During the recent examination of the territory of the Mistetsky Arsenal [literally: “Arsenal of Arts”] museum complex in Kiev, archeologists discovered traces of Lavra fortifications from the 1490s and 1500s. This indicates that in the early sixteenth century nuns still lived on the territory of the Lavra and not outside it.

From two Moscow documents of the 1580s we learn that the female community of the Caves received government monetary aid from Moscow separately from the main Lavra’s male community. In all probability, the threat of a Tatar raid on Kiev had been recognized as non-existent shortly before. It enabled the authorities to “distinguish” the Convent of the Caves nuns—they “were worthy” of a separate section in the reports of the financing of the Lavra by Moscow princes.

The original location of the female community within the Lavra was probably the so-called “Hospital Convent”—a part of the upper Lavra near the Holy Trinity Church-over-the-Gate. As is generally known, convents in the Middle Ages had the duty of medical care as part of their obedience. In this case, after their “move”, the nuns lived just some fifty meters [c. 164 feet] away from their previous home—on the other side of the gateway Church of the Holy Trinity and the adjacent walls.

In the 1610s, the famous Lavra abbot, Archimandrite Elisei (Pletenetsky), arranged the construction of the permanent wooden structure of the Maidens’ Convent of the Caves, which was very lavishly adorned inside. We know this from the ode of 1618 that was dedicated to him. From that time on, the convent was mentioned very actively: in the wills of the Ukrainian gentry, in the notes of the Holy Hierarch Peter (Moghila), and in quite a number of other documents.

On a map of the Lavra of 1638, the location of the Maidens’ Convent of the Caves is indicated on the site where the Old Arsenal stood from the late eighteenth century (now the Mystetsky Arsenal museum complex). In the map description the convent is referred to as “a convent for unmarried noblewomen, with many daughters of princes, governors and gentry among the nuns.”

In the language of documents: The convent’s prosperity

In his famous notes, the French engineer Guillaume Le Vasseur de Beauplan (c. 1595-1673), who worked in Ukraine from 1630 until 1647, provided a more detailed description of the Maidens’ Convent of the Caves during the period of its blossoming. According to him, there were over 100 nuns at the convent at that time.

The Frenchman was amazed that the sisters had a right of free exit from the convent and were allowed to walk to Kiev, which was half a league (that is, over 1.24 miles) away, through woods. The Parisian was also surprised that guests had a right to pay a visit to the nunnery freely—in contrast to Western European convents with their very strict rules.

He and dozens of other travelers after him related that embroidery of exquisite craftsmanship was the convent’s sisters’ major activity and source of revenue. The Kiev Caves Lavra Reserve houses some examples of this work to this day.

After the victories of Hetman Bogdan Khmelnytsky (c. 1595-1657) [over the Poles.—Ed.] the new Cossack authorities had to confirm the land ownership of all proprietors many times. A decade later, the Moscow authorities were obliged to do the same. Thus, a charter of Hetman Khmelnytsky of 1648 testifies to the fact that the Pidhirtsi village between Kiev and Obukhiv was the first estate of the Maidens’ Convent of the Caves. A letters patent of the Tsar of Moscow of 1659 assigned not only Pidhirtsi, but also the neighboring village of Khodosovka to the nuns. By the by, half a century later the total number of villages near Kiev with their lands in the possession of the convent was about twenty.

In 1652, Kiev was devastated by the plague pandemic, from which around 300 Lavra monks along with over 100 sisters of the convent died. The prayer list for the departed of one of the churches of the Near Caves gives the names of forty-two novices, fifty-nine ryassophore nuns, and two abbesses of the convent who were victims of the plague.

According to Archdeacon Paul of Aleppo

Two years later, in 1654, Patriarch Macarios III Zaim of Antioch (1647-1672) travelled through Kiev to Moscow. His son and secretary, known as “Archdeacon Paul of Aleppo”, left his notes of that visit in Arabic. Father Paul gave a very detailed description of the Maidens’ Convent of the Caves in them.

According to his evidence, there were fifty to sixty sisters at the nunnery—the community had obviously dwindled as a result of the epidemic. The traveler related that the abbess of that time belonged to the family of a Polish king. Perhaps the author of the memoirs was mistaken here and the abbess belonged to the Rurik family—Rurikids had been a dynasty of local “kings” (from the ninth century till 1598). The archdeacon wrote that most of the nuns were members of ancient noble families, and also many orphaned girls were brought up at the convent before their coming of age.

The Syrians were amazed by the solid scholarship of high-ranking nuns who had a good understanding of philosophy and logic and wrote their own works. Archdeacon Paul did not fail to describe the interior of the church, which abounded in gold, silver, gems and pearls; he added with amazement that saintly women were depicted on most icons: holy female martyrs, virgins, and righteous women. With still greater amazement he also described the sisters’ clothing (which was very traditional for these lands) along with the food and drink with which they entertained their visitors, including even horilka [an Ukrainian alcoholic beverage]. Lastly, the guest spotted the convent’s well with a two chain system that indicated a depth of several dozen meters.

According to the traveler’s account, it took the Syrians a long time to get to the Lavra along the convent’s territory. It means (and other sources confirm this) that, apart from the cloister itself, the convent’s wall also surrounded its numerous orchards, flower gardens, and kitchen gardens, which stretched very far behind the rear façade of the present-day Mistetsky Arsenal, along what is now Tsitadelnaya Street.

What is interesting here is that Archdeacon Paul (as opposed to Beauplan) decided that laymen were forbidden to visit the Maidens’ Convent of the Caves at all, whereas these may have been only temporary quarantine restrictions after the pandemic, which would have applied to all visitors.

Abbess Mary-Magdalene

The dedication of the Maidens’ Convent of the Caves is first mentioned in 1654. It was dedicated to the Ascension of the Lord. The six-domed wooden Ascension Church was presumably built there in the early 1640s, and its creation was associated with the name of St. Peter (Moghila), Metropolitan of Kiev.

In the 1660s due to the Polish-Cossack-Tatar War (1666-1671) and the Russo-Polish War (1654-1667), the monasteries of the Kiev Caves became impoverished, and they appealed to the Tsar of Moscow for help. The aid was received—in 1669 a large amount of money was donated to the Maidens’ Convent of the Caves.

From 1681 until 1707, the Maidens’ Convent of the Caves was ruled by Abbess Mary-Magdalene (Mazepa; secular name Marina or Marianna Mokievskaya, 1617-1707), mother of Ivan Mazepa (1644-1709) who became Hetman of Ukraine several years after her appointment as abbess. It is known that the husband of Marianna Mokievskaya, Stepan Adam Mazepa-Koledinsky (d. 1665), and all his family had been included into the prayer list of the Lavra’s Near Caves long before the rise of his son Ivan’s career. This is indicative of the long-standing ties between the noble family and the convent. And it is most likely that the then General Esaul [Cossacks’ captain—ed.] Ivan Mazepa as the office holder was not involved in the appointment of Abbess Mary-Magdalene.

Doubltess soon after his mother’s elevation to the abbacy, General Esaul—afterwards Hetman Mazepa—gave many gifts to his mother’s nunnery. Among them were: a big bell with an inscription of “1683”, which now hangs in a bell-tower of the Lavra’s Near Caves; quite a few settlements with land; huge sums of money; and jewels, including those from the Tsar of Moscow—these were the gifts to the abbess as to a representative of the royal family. According to some sources of that time, both the abbess and the hetman paid visits to Moscow almost annually.

On top of all that, in 1690 the Maidens’ Convent of the Caves acquired its own relic—the miracle-working Rudnya icon of the Mother of God. However, they couldn’t avoid a conflict. The translation of the icon to Kiev offended the parish of the Rudnya village in Chernigovshchina [in what is now the Chernigov region], where the wonderworking icon had been discovered a year before and where a new large church had just been completed (it was supposed to attract pilgrims flocking to the icon). But “with some people it is best not to argue”,[2] and it was decided to keep the icon in Kiev. Afterwards, the holy Rudnya icon was kept at the Florovsky Convent of the Ascension in the Kiev neighborhood of Podil, and following its closure in the twentieth century it disappeared forever.

The main item built with the generous sums donated and the chief achievement of Abbess Mary-Magdalene at the Maidens’ Convent of the Caves was the huge stone Ascension Cathedral that was completed by 1705. At the same time, from the 1690s the new convent’s ensemble was in fact created: a refectory, cells, a paved square, the wall, a gate tower, and a belfry.

But the ways of God are past finding out! As soon as the convent was completed after the decades of unceasing labors, as soon as all the things were put in order and all was finished “at the top level”, its fate was sealed forever.

The liquidation

In the 1700s there was a prolonged military conflict between Russia and Sweden, at times between Russia and Turkey, and there was no confidence in Poland’s loyalty, so Kiev could have been siezed at any moment. For the protection of its strategic position, Peter I organized the building of the Kiev Fortress in 1706.

Its layout included the buildings of the Kiev Caves Lavra, but in fact everything surrounding the Lavra was condemned to destruction. This applied, first of all, to numerous settlements of free peasants and gardeners attached to the Lavra (and, partly, to its convent). However, the “sword of Damocles” hung over the Maidens’ Convent of the Caves itself, since it stood beyond the new solid Lavra’s walls, which became a part of the fortification system.

Undoubtedly, nothing could prevent them from making the convent a part of the fortress. But Tsar Peter and his inner circle (especially Prince Dmitry Mikhailovich Golitsyn (1665-1737), who then was Governor General of Kiev), pursuing their policies of state control over the Church, were happy to abolish as many monasteries and convents as possible and to weaken the Lavra, even if they were unable to close it.

Before the victory in the Battle of Poltava (1709) construction work was carried out in other places (on the slopes of the Dnieper River) though, so ninety-year-old Abbess Mary-Magdalene thankfully did not live to see the devastation of her beloved abode. She had passed away before the destructions began, in 1707, much worrying about the “clearing” of the site for making a military town. However, her successor, a relative and namesake, Abbess Mary-Magdalene (Mokievskaya), had to leave the newly-built beautiful convent and move to the Florovsky Convent in Podil in 1711-1712 together with all her sisters.

The pretext for the move was inexorable in the royal manner: The barracks and depots of the many-thousand-strong garrison of the Kiev Fortress were to be located by a source of water, and there was only one such source on the hill, which belonged to the nuns. It was much more convenient to locate the garrison near Mazepa’s new walls of the Lavra—in this case the military base was already protected from one side by a wall. And, moreover, they needed a large church near the barracks as it was not a good idea for thousands of soldiers and fortress workers to attend the Lavra services all together.

In addition to this, in 1710 Kiev was stricken with the plague pandemic which halved the community of nuns at the Maidens’ Convent of the Caves, while Tsar Peter stressed that there would be no more financial support of monasteries by the tsar or his governors. This meant that maintenance of a large urban development would have been an intolerable burden for the nuns (even notwithstanding the wealth of their relatives).

Thus, it was the unavoidable, imminent degradation that Governor Dmitry Golitsyn pointed out to the inhabitants of the Kiev Caves Lavra before closing its convent, and as a “compensation” he built a skete for monks in Kitaevo—a historic area in the Kiev suburbs.

After the convent

Until the late 1740s, only nuns who had moved from the Maidens’ Convent of the Caves became abbesses of the convent in Podil. It was called “the Ascension Convent”, “the New Ascension Convent”, or “the New Maidens’ Convent”. In the mid-eighteenth century, its main temple was dedicated to the Ascension of the Lord—and this church stands to this day. Only in the early nineteenth century did its colloquial name form appear again—the Florovsky Convent.

The plentiful villages with ample lands from the old Maidens’ Convent of the Caves were not taken away by the state (which pretty often was the case under Peter I, who strove to close as many monasteries as possible), but were inherited by the Florovsky Convent. That was something at least! However, half a century later monasteries and convents were nevertheless deprived of their lands.

The second stone church on the site of the former Maidens’ Convent of the Caves—the refectory Church of the Protection of the Virgin Mary—was immediately closed. It then housed the fortress’ money depot; treasurers and stewards of the garrison took up their quarters in the refectory, and the cells and the abbess’ residence housed the arms and ammunition dump and a repair shop. Wooden sheds for storing the ammunition were built all over the territory of the former nunnery.

The main Ascension Church of the former Maidens’ Convent of the Caves functioned amid these storage areas for more than another half a century as the church of a local military unit. However, in the troubled times—the 1720s until the late 1740s—the Kiev Fortress suffered a lack of financing, the church was not repaired, and it became dilapidated. Afterwards, under Catherine II (ruled 1762-1796), it was closed under the pretext of a fire hazard: They said that candles and icon lamps were burning there just stone’s throw away from a large ammunition supply point.

In the 1780s and 1790s, the stone Old Arsenal (now the Mistetsky Arsenal museum complex) was built for storing and producing this ammunition and for repairing guns. Sections of its walls were built right over the foundations of the former altar of the trapeza church dedicated to the Protection of the Mother of God in the Maidens’ Convent of the Caves. The very walls of the military facility were built with bricks from the long abandoned Ascension Church (completed by 1705) along with materials from other former monastic buildings—the Arsenal’s builder had pulled all of them down before beginning the Arsenal’s construction.