THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE CHURCH

|

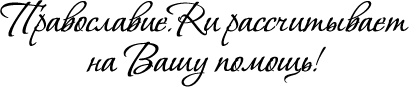

| The church of Savior's Ascension, Mount of Olives |

In time, Fr. Antonin began to construct the church. Construction, however, proceeded at a very slow pace, and was repeatedly interrupted. The walls had already risen to a height of nearly seven feet, and the windows had been started when, in 1876, the construction on the church came to an end because of lack of funds. Another reason, as Archimandrite Cyprian (Kern) explains, was the difficulty in procuring various permits (firmans), in finding a way around the Turkish laws, in persuading officials of the court to cooperate, etc. The founding of churches and Christian schools during the Turkish period was fraught with particular difficulties. It is said that a certain Salim-Effendi was very well-disposed toward Fr. Antonin. This Mohammedan loved to drink tea, and Fr. Antonin was able to supply him with Russian tea of high quality. Undoubtedly the personal charm of the chief of the Mission overcame many difficulties and made his tasks easier.

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877, during which Fr. Antonin had to remove himself to Athens, further delayed construction. Only in 1885, fourteen years after construction had been begun, was the church ready for consecration. It was constructed following the pattern of ancient Byzantine churches, being cruciform and replete with a dome, modeled on that of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, which sat on an eight-sided drum with twenty-four windows. The iconostasis was imported from Moscow. On the cliroses one can see the remains of two columns from the ancient church. The floor is paved with marble flags in the middle of which are visible fragments of "white marble from one of the most ancient churches of Jerusalem" which Fr. Antonin had discovered.

But before the consecration, new difficulties arose. Nicodemus, the Greek Patriarch of Jerusalem, lodged a complaint in St. Petersburg against the "great scandal" supposedly caused by Fr. Antonin when he decided to name his new structure the "Church of the Ascension," whereas the site of the Ascension is not situated on Russian property. On the basis of this protest, Fr. Antonin had to rename the church on the Mount of Olives the "Church of the Savior," in an attempt to resolve the conflict. Later the church would become known as that of "the Savior's Ascension." At the present time, its original appellation has been restored.

At the same time as the church, a four-tiered, 210-foot high bell-tower was erected. It was designed by Italian architects, and was also built at a very slow pace.

As often as his work would permit him, Fr. Antonin would visit the Mount of Olives; and even when he was occupied with other matters, he would observe the construction from the corner window of his residence at the Mission with the aid of a telescope. When construction was completed on the bell-tower, the main bell arrived by steamship at Jaffa. It weighed 11,123 pounds, and measured nearly seven feet in diameter. It had been donated by a close friend of Fr. Antonin, A. B. Riazantsev, a merchant of Solikamsk. In August of 1885 this bell, thanks to funds provided by Countess O. E. Putiatina, was conveyed from the wharf to the Russian garden in Jaffa, near the tomb of St. Tabitha.

The

problem of moving it to the Mount of Olives remained.

Fr. Antonin then issued a call to the Russian people:

"Are there no loving Christians who will help

raise Jerusalem's 'Ivan Veliky'[i]

to the Mount of Olives? This is an urgent

task." "And behold," writes Fr. Antonin,

"105 people (two-thirds of them women) arrived in

haste at Jaffa on Tuesday and set about the work.

Thanks to the general enthusiasm, and despite a

thousand difficulties, seven days later the bell

successfully arrived (by hand!) at our tower. On

February 5, in the evening, it was solemnly met,

rousing the entire city. Then hordes of pilgrims

arrived, out of nowhere, as it were, to drag the bell

to Holy Olivet, to the place appointed for it."

The magnificent bell-tower of the Russian Church of the

Ascension on the Mount of Olives, known as the

"Russian candle," is now visible from all

vantage points in the area of Jerusalem. From its

pinnacle one can clearly discern the Dead Sea and the

region beyond the Jordan River; and with the aid of

binoculars, on a clear day one can even see the

Mediterranean Sea. Its largest bell is audible for

miles, loudly bearing witness before the heterodox

to the successes of the Russian activity in Palestine,

and causing incomparable spiritual delight for the

Russian Orthodox people. Fr. Antonin had a particular

fondness for the deep, dense ring.

Pilgrims moving the bell from Jaffa to the Mount of Olives.

Finally, despite all the difficulties, on June 7,1886 (O.S.), the solemn consecration of the church and bell-tower took place. Even Patriarch Nicodemus—this time, at least, well-disposed—attended. He delivered a panegyric sermon in honor of Fr. Antonin, the builder of the church, and his closest assistant in the great task, Hieromonk Parthenius, and even bestowed a pectoral cross upon the latter.

FATHER ANTONIN

Archimandrite

Antonin (secular name: Andrew Kapustin) was born on

12 August 1817, into a family of long-standing

priestly lineage, in the village of Baturino, in the

Shardinsk District of the Province of Perm. After a

primary education received at home, Andrew attended

the district theology school.

The generations which passed through such schools and seminaries received a classical education such as secular schools were never able to provide. Fr. Antonin, thanks to this schooling and his further training in seminary and theological academy, mastered the Greek, Latin, and Hebrew languages, and had a working knowledge of Tartar. In the Levant, he learned Modern Greek well and spoke it fluently, and even added two more languages to his repertoire—French and German. It is not possible at this far remove to say whether he knew Turkish and Arabic well; but, living in the Levant, as he did, for thirty years, it is probable.

Later, Fr. Antonin graduated from the Kiev Theological Academy and taught there. In 1850, his ministerial career took a radically different direction: he was appointed rector of the embassy church in Athens, where he remained for ten full years. This was the period of his first great discoveries in the area of Byzantine archeology. He rebuilt the ancient Athenian 'Lykodemos' Church on the ruins of the ancient church (this subsequently became the embassy church), finding in it interesting ancient Christian burial inscriptions. These he published in 1874. The five subsequent years (1860-1865), Fr. Antonin spent as rector of the Russian embassy church in Constantinople, which also widened his knowledge and introduced him to a new circle of acquaintance with influential Russians and Greeks in the Near East.

Finally, in 1865, Fr. Antonin was appointed to Jerusalem and became head of the Mission, or the "pilgrimage organization" as they used to call it. Its task was to care for and feed the huge number of Russian pilgrims in the Holy Land who, every year, right up to World War I, arrived in the tens of thousands. When Fr. Antonin arrived in Palestine, the only building standing was the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity, which stood in the middle of the then-recently-begun "Russian Compound"—intended as lodging for pilgrims. It was then that Fr. Antonin conceived the idea of buying parcels of land and building Russian churches on them, where Russian pilgrims could pray in their native tongue. Hospices were also needed, and in great numbers. But troubles began to arise. Palestine was then under the Turkish rule, and, since foreigners were prohibited from buying land, such purchases could be made only in the name of absentee owners who were Turkish citizens. Fr. Antonin acquired land in the name of his faithful assistant, J. E. Halebi, the Mission's dragoman. "Jakob Egorovich has adorned my whole life," Fr. Antonin said of him. Often there was no money, because the Russian government did not provide Fr. Antonin with any funds for purchases. He had to rely on donations elicited from the pilgrims. Only the energy and determination of Fr. Antonin brought to completion the work that to this day astonishes everyone who visits the Holy Land. During the twenty-nine years of his activity, Fr. Antonin purchased thirteen parcels of land, covering a total area of over 105 acres, which became the property of the Mission, confirmed by deeds of ownership (kushans and senet-tugrals). The cost of these parcels of land, according to Fr. Antonin's account to the Most Holy Synod at the time of his death in 1894, was approximately one million rubles.

In point of fact, he was personally responsible for the acquisition of almost all the Russian property in the Holy Land: Gomei, Gethsemane, the caves of the prophets, the oak of Mamre, the gardens in Jericho, and the area around the grave of St. Tabitha, including her actual tomb. His never-flagging energy astonished his contemporaries.

This

is how Prof. A. A. Dmitrievsky describes a typical

day in the life of Fr. Antonin: "The door of his

cell stands open from early morning until late in the

evening. Early in the morning he receives native

Arabs, resolving their disputes, offering sage

advice, providing them with material assistance in

the form of necessities and money; next come the

teachers of the schools founded by him, and members

of the Mission, asking his counsel and decisions. And

at all hours, the Russian pilgrims approach him

freely and trustingly: officials, merchants, and

peasants, rich and poor alike, in the hope of finding

in him a resolution of the questions that trouble

them. And Fr. Antonin gladly converses with each at

length, and thus has managed to win many over to his

side and make them active proponents of the work to

which he has given his whole soul. Only late in the

evening does he find himself alone, though not

entirely alone: his friends are his beloved books.

From late evening to late at night he sits poring

over some old manuscript or folio, at times

conducting important archeological research, at times

carrying on a correspondence with newspapers or

private individuals; then, armed with a magnifying

glass, and having at hand the best numismatic

publications, he will bring all of his ocular

power to bear on some ancient passage in an old

manuscript or device on a Greek coin (Fr. Antonin was

an avid coin-collector); then, withdrawing to the

observatory he had installed on the roof of the

Mission, he will spend some time studying the

wondrous firmament of the sky with its diversity of

luminaries. Then he will sit over his own chronicle,

recording his thoughts, feelings, ideas, and

impressions of the past workday, thus leaving the

future historian of our time priceless material for

reference; then, finally, equipped with a needle, he

will mend his old riassa or hole-riddled stockings

The noise of the samovar on the table, and tea, the

'favorite drink of his faraway homeland,' are

constantly present in his office during his evening

work… After such a day, often very early in

the morning, he can be seen returning from the

Russian building projects in the company of his

faithful dragoman, Jakob Halebi, having 'made the

tour of his diocese,' as those inclined to humor put

it, having in mind the building projects

underway at the Beth-Jal hostel, or the hospices in

Hebron, Gomei, Jericho, and other

places."

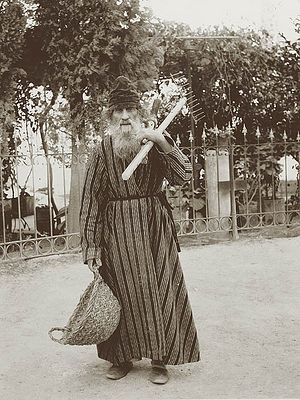

Fr. Antonin with pilgrims, in the last years of his life.

It ought also to be mentioned that, despite all of his activity, Fr. Antonin unfailingly read the daily services prescribed by the monastic rule. When did he sleep?

"All of his contemporaries and colleagues who remain alive speak of Fr. Antonin's modesty and unpretentiousness," writes Archimandrite Cyprian (Kem). "His old garments; his extremely plain meals, often consisting of a single plate of the large black beans beloved of the Arabs, and sustenance never augmented by the meat customary among and favored by the monastics of the Levant, characterized the usual fare of the chief of the Mission. He was not afraid of demeaning the prestige and dignity of his official position by his modest life and labor. More than once, people unacquainted with him, finding him cleaning his own cell and taking him for the attendant, would ask him to inform the Archimandrite of their arrival, and shortly thereafter would be astonished and embarrassed when the selfsame 'cell attendant' appeared before them in an ample Greek-style riassa, in the person of the chief of the Mission."

Thus did the ever-memorable Fr. Archimandrite live in the Holy Land for twenty-nine years, laboring day after day without rest.

FATHER

PARTHENIUS AND THE FOUNDING OF THE MOUNT OF OLIVES

COMMUNITY

Fr.

Parthenius (whose secular name was Parmenius

Timofeyevich Nartsissov) was the son of the preceptor

of the village of Zagradchina, in the Rannenburg

district of the province of Riazan. Because of his

poverty, he completed only three grades of church

school. Thereafter, he assisted his father on the

cliros. At the age of fifteen, he became a novice in

the Dankov Monastery. In 1879, at the age of

forty-eight, having already been ordained to the rank

of hieromonk, he visited the Holy Land as a

pilgrim.

Hieromonk Parthenius

"There," writes Prof. Dmitrievsky, "he became close with Fr. Antonin Kapustin, the chief of the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission, on whom Fr. Parthenius made a very favorable impression. At first, Archimandrite Antonin appointed him to perform the daily services in the Cathedral of the Holy Trinity (in the Russian Compound).

"In the time he had free from serving, Fr. Parthenius loved to spend whole days and even weeks on the Mount of Olives, living in a little room at the hospice for pilgrims. He kept a careful watch over the construction then under way and the excavation of the ancient buildings and burial crypts. Finally, when the church was completed and consecrated in 1886, the divine services were permitted on Thursday and Sundays, as well as on feast days. Fr. Parthenius became the only priest to perform the services, attracting Russian pilgrims who knew the order of services and had good voices to participate in them. His services, which were full of reverent simplicity and total spiritual unity in prayer between pastor and his ever-changing flock, were assiduously and devoutly attended by the pilgrims, who loved the simple Fr. Parthenius fervently for his truly Russian hospitality on the Mount of Olives."

After the consecration of the church

and the bell-tower, Fr. Parthenius' care for the

Russian Olivet not only did not cease, but increased.

The indefatigable elder Fr. Parthenius labored

continually in his chosen portion, excavating the

necropolis (the ancient cemetery), clearing away the

accumulated refuse, which had built up over the

mosaic floors of the ancient temples and buildings.

He made uneven areas and depressions level,

installed cisterns for the collection of rainwater,

and dug pits for the planting of trees. In his daily,

tireless work, he tried to do everything with his own

hands, trusting in the good health with which God had

blessed him. At times he would carry soil on his own

shoulders to fill in the uneven places and to pour

around the trees he had planted, at times he would

carry water in goat skins from far away, when there

were still not enough cisterns on the Mount of Olives

to furnish water for the saplings and flowers which

he cultivated lovingly. All the present beauty, all

the many stands of cypress, olive, and pine trees are

the work of the tireless hands and sturdy shoulders

of Fr. Parthenius. Moreover, one ought not to lose

sight of the fact that Fr. Parthenius' enemies in

this work were not only the stony, arid soil and

burning sun, but the half-wild, thieving Moslem

inhabitants of the neighboring villages, who, at the

first available opportunity, under cover of night

repeatedly removed stones from the boundary walls of

dry masonry, uprooted his flowers and herbs, stole

his seedlings, and even carried off his meager

personal necessities. When day broke, the elder would

survey with pain of soul the traces of his neighbors'

depredations. He would complain bitterly about

them to his occasional visitors, but would not annoy

those who offended him, trying instead to live with

them in peace and harmony, and continuing with

redoubled energy to work on his beloved

grounds.

Fr. Parthenius by one of his wells.

Anyone

who visited Jerusalem and knew the late elder

described him in the same way: slight of stature,

thin, with kindly blue eyes, bright red, straggly

hair, and a long, bushy beard, which turned gray in

old age, taking on an ashen color. He was a very

animated man and somewhat fussy, speaking the Great

Russian language rapidly. His face was kindly and

sympathetic. He invariably dressed in a simple motley

cassock of the cheapest material.

Sisters of the convent gathering olives from the trees planted by Fr. Parthenius

Fr. Parthenius' reputation grew among the pilgrims and inhabitants of Jerusalem; donations flowed in to him for the Mount of Olives church in abundance. At the same time, there also arose, of course, unfavorable rumors among wicked people concerning his personal, monetary resources. Actually, in his non-acquisitiveness, Fr. Parthenius owned practically nothing, for all the moneys received from well-wishers he spent on the church, the planting of trees, and the feeding of pilgrims.

One ought also to mention that Fr. Parthenius was a great man of prayer. In the portion of the Olivet property furthest to the south, far from the buildings in which people lived, he dug out a cave with his own hands, where he often would spend a whole night keeping vigil.

On 24 March 1894, Fr. Antonin reposed. Several years later, in 1903, Archimandrite Leonidas (Sentsov) became the chief of the Mission. He had travelled to Jerusalem as a student, had come to know Fr. Parthenius, and supported his cherished desire to build a convent on the Mount of Olives.

Although

the idea of founding a men's monastic community on

the Mount of Olives belonged to Fr. Antonin, who had

intended to found a monastery there, Fr. Leonidas

rejected this idea, because in all the many years

that had passed, there had been only one monk willing

to live there: the monk Pambo, who served as

watchman. It was his responsibility to let pilgrims

in through the eastern gate when they came up to the

Mount of Olives from Bethany, and to let them out

through the western gate when they wished to go on to

the "Russian Compound." For this reason,

Fr. Leonidas decided to establish instead a women's

convent on the Mount of Olives.

Arial view of the convent.

In 1906, the Convent of the Mount of Olives was formally established by the Most Holy Synod. Fr. Parthenius was appointed abbot. The nun Eupraxia, who had come to Jerusalem in 1880 from Moscow's St. Alexy Convent, was appointed superior (her secular name had been Maria Milovidova). On August 12, 1906, the birthday of Fr. Antonin Kapustin, the community was solemnly opened. It consisted originally of fifteen sisters. By August of 1914 it had grown to 150. Later, almshouses, studios for iconographers and goldsmiths, and a refectory were built.

Fr.

Parthenius continued his labors of construction,

excavation, and planting, by his unflagging energy

inspiring all to take part in the work.

The cell where Fr. Parthenius was killed

On the night of January 14-15, 1909, his ascetic life was crowned with martyrdom. After the workday, Fr. Parthenius withdrew to his solitary home; but in the morning, he was found lying on the floor in a pool of blood, a deep wound in his neck. On the floor, the prints of bloody feet were visible; his possessions were in disarray, his drawers obviously rifled, as though someone had been searching for something. His murderers were never discovered, nor was their motive ever clarified. This venerable man, highly respected and beloved by all, his loss lamented not only by Russians but by foreign friends as well, was buried outside the Church of the Ascension, next to its northern wing, at the feet of his beloved elder, Fr. Antonin. "I am a novice of Fr. Antonin, and wish to lie at his feet," the ever-memorable Fr. Parthenius had said when he was alive. His desire was fulfilled.

From Святой Елеонъ, The Mount of Olives Convent 1886–1986, (Jerusalem: Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jerusalem, 1986), 129–138. Posted on OrthoChristian.com with permission.

Nun Taisia (Ostrikova), Nun Marina (Chertkova), Vladimir Dauvaldier