The Ladder of Heavenly Unity

Moses approached the divine fire of the Burning Bush with the footsteps of his mind bare, completely free from any human trains of thought, wrote Saint Maximos the Confessor.

Moses approached the divine fire of the Burning Bush with the footsteps of his mind bare, completely free from any human trains of thought, wrote Saint Maximos the Confessor.

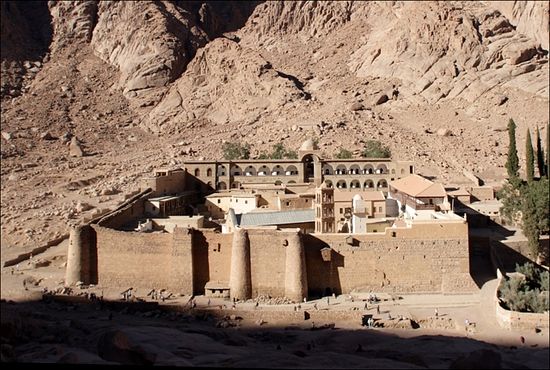

Continuing Orthodox monasticism’s oldest unbroken tradition, Sinai monks still liturgize, shoeless, over the roots of the Burning Bush. On the holy ground where Moses was commanded to remove his sandals – together with all earthly logic – monks turn diversity’s polarizing forces to unity – some of the ways St. Catherine’s Monastery of Sinai brings Byzantium’s patristic spirit into the modern era as living tradition.

One need look no further than the Monastery’s name for evidence of its universal relevance: no one really knows how or when the “Sacred and Imperial Monastery of the God-trodden Mountain of Sinai” became popularly known as St. Catherine’s – just that the change took hold as the Saint’s renown escalated throughout Europe and Russia. This transpired after her miracle-working relics were brought to Rouen by monks in the 11th century.

As magnet to pilgrims from every corner of the globe, the Greek Orthodox monastery embodies a past steeped not in its own reflection, but in the purity of Christ’s message. In the words of Sinai elder Father Pavlos, “Authentic love is to preserve the truth as we received it, so we may hand it on, unblemished, to those who come after us.”

At the heart of this discipline beats the Sinaite love for simplicity of soul. With freedom from sin as its object, simplicity accepts nothing man-made in place of the freedom granted humankind in Genesis – freedom not to choose between right and wrong, but from the constant necessity of doing so. Before shedding the divine likeness by failing to return God’s love, the simplicity of human nature was afflicted by none of subsequent humanity’s drift toward sin.

And the heart of simplicity of soul? The elder’s answer again betrays the clarity of an ascetic lifetime devoted to prayer: “Love God first, above all else.”

The altar of the “Holy of Holies” of St. Catherine’s Monastery is placed directly over the roots of the Burning Bush, which still thrives outside the chapel. (Photo Credit: Bruce M. White Photography)

The altar of the “Holy of Holies” of St. Catherine’s Monastery is placed directly over the roots of the Burning Bush, which still thrives outside the chapel. (Photo Credit: Bruce M. White Photography)

Monks at the Burning Bush devoted their first chapel to the Annunciation, the announcement to theTheotokos that she was selected by God to bestow human nature upon His Son. He who was begotten before all ages without a mother, would now be born without a father – if the Virgin agreed. Without her free consent the Incarnation could not take place – but what human logic could process such tidings? The Holy Virgin did not stop even to contemplate the censure, and worse, that greeted unwedded motherhood in her society. Loving God before herself, she loves others not for the return of their good opinion, but with the boundless love of God for their soul. With her heartfelt “yes,” the living “ark of the covenant” is overlaid with gold, not by human hands to contain the words of the Law given to Moses on Sinai – but by the Holy Spirit, to contain the uncontainable Word Himself. It is due to the purity of her love for God that a simple Maiden becomes the inexhaustible Treasury of life for mankind, and in the shadow of Mount Sinai, the First commandment does not just precede the Second, it renders it possible. Only by loving God above all else can we hope to love others, according to Father Pavlos:

“Love begins in God. First we love God above everything and everybody. Then ourselves, for Christ said to love your neighbor as yourself. Love then goes out from us to other people, and finally, to all of Creation. (Saints have exceeded this by loving others more than themselves, but Christ does not ask this.)”

Rays from the Holy Summit engulf all ages in the limitless love of the Crucified Christ during services preceding Holy Pascha (Photo Credit: Bruce M. White Photography)

Rays from the Holy Summit engulf all ages in the limitless love of the Crucified Christ during services preceding Holy Pascha (Photo Credit: Bruce M. White Photography)

Saint Paul notes that Christ died for us while we were yet sinners. Lacking the simplicity of the divine likeness, our own love does not so generously tolerate our neighbor’s foibles.. But in loving God first, beyond all else, we surpass our limits through union with the Source of love. When God comes to abide, to energize within us according to His perfect will, empowering our human energies with His divine ones, the inexhaustible stores of that love become our own. In the nuanced idiom of Saint Isaac the Syrian:

Love incited by something external is like a small lamp

whose flame is fed with oil, or like a stream fed by rains

where flow stops when the rains cease. But love whose object is God, is like a fountain gushing forth from the earth.

Its flow never ceases, for He Himself is the source of this love

and also its food which never grows scarce.

Consistent with the imagery of the Burning Bush, whose flaming branches are illumined, but never consumed, by the divine fire set alight in the soul by the Word of God, the ascetic theology of the Sinai school burns with a fire that unifies in an incorruptible way, for it neither supports the characterization of peoples, nor their homogenization. Both monks and their Bedouin neighbors attest to bonds of cooperation that go back 15 centuries. Unhindered by different faiths, each group reaches out to the need of the other. And when the Sinai was administered by the Israeli government from 1967-79, things were very much the same. It is through our brother after all, that Christ wishes to reach us. As a result, without condescension to the sin of “people-pleasing” (cultivating others’ good opinion), a Sinai monastic soon learns to protect the inner peace of others, in order to enjoy his own.

The earliest literature attests to the operation of an infirmary by the Monastery for the benefit of its desert neighbors, a custom modernized by today’s monks with donated, state-of-the-art equipment, and assistance with medicines and basic provisions. But the currents of mutual peace in this environment run much deeper than the superficialities of economic philanthropy: The Sinai tradition is rooted in profound respect for the freedom of others – the philanthropy of the Holy Trinity.

The granite wilderness is a soft and beautiful one, of many hues. But the lack of greenery starves the soul for the consolation of foliage. One turns inward for shade, to the only refuge available, the shelter of the will of God, for as the mountains suspended all about gently confide, there is no other.

The two-headed eagle of the Byzantine empire symbolizes unity in diversity, the continuity of empire from West to East, union of past and future in fidelity to the Word of God. (Photo Credit: Peter G. Angelides)

The two-headed eagle of the Byzantine empire symbolizes unity in diversity, the continuity of empire from West to East, union of past and future in fidelity to the Word of God. (Photo Credit: Peter G. Angelides)

Accepting and accepted by all, without sensing any need to blur the distinctions that characterize its own confession of faith, it is a question how the Sinai community retained its Greek identity under the successive political pressures of so extended a timeline, in a far flung outpost of the empire, indeed, so many centuries after its fall. Or, more to the point, how did the community’s Greek identity absorb successive influences into a “unity of diversity,” rather than the opposite – the diverse “unity” that eats away from within at the civilizations of the so-called “Enlightenment?” Having never bowed to demands that replaced the glorification of God with that of man, the eternal present of Mount Sinai spans untold ages as night yet hands its glory to day, and day to night, in the incandescent liturgies of the Burning Bush chapel. Illumined only by the flicker of candlelight on golden mosaic, enigmatic mysteries locked within early antiquity’s sacred masterworks emerge into relief with each approaching dawn, only to recede once more into the shadows of midnight vigils, as subdued tones of ancient Byzantine chant suggest that the sixth century simply never ended in Sinai.

Of course, the Byzantine identity that yet typifies the community has always extended beyond the Greek one, in the modern sense at least, if it reflected the collective consciousness of what was then considered the civilized world. Does it suffice then, to note that Byzantium’s culture always transcended provincial limits, in that, following Roman precedent, the empire united the plethora of cultures surrounding the Mediterranean under a commonality of shared values?

Viewing the sunrise from the Holy Summit of Sinai has been likened to seeing the creation of the world.

Viewing the sunrise from the Holy Summit of Sinai has been likened to seeing the creation of the world.

Shared values however are not moribund ones. The momentum of classical philosophy’s relentless search for truth fueled the tension between Greek Christianity and Platonist schools that innervated the intellectual life of late antiquity well into the Byzantine era. Tracing the influence of Hellenistic and Judaic thought upon one another through the evolution of classical concepts like divine energeia, as the first monastics sought union with God in the Uncreated Light of the Burning Bush, it quickly emerges how dynamic were the prevailing forces that preserved the Sinaite worldview from the idiosyncrasies of self-absorption. The visions that shaped it were too disparate; their sources too deep in the ancient world.

Despite the Monastery’s location on the remote frontier of the empire, the literature proves Sinai’s early monks to have been surprisingly tuned in to the currents of their times. Anastasios of Sinai for one, is noted for his prolific writings on the monothelite controversies of the seventh century; before him, John Klimakos demonstrates fluency with theological concerns throughout his Ladder of Divine Ascent, remarking at the outset that following Christ is contingent upon accurate belief in the Holy Trinity. Reading Monastery history by the light of its own legacy, Sinai Librarian Father Justin cites the complexity of Sinai’s vast manuscript collections as evidence of a world “more interconnected than scholars have often been willing to grant.”

It is said that a society disgorges both its least and most innovative personalities to distant shores. If so, those who landed on the Sinai’s presumably populated the creative end of the spectrum; unable to assimilate and adapt, who could have survived such a harsh environment? More to the point, who could have met the challenge of its granite silence? “Unless a man’s heart has first been filled with the presence of God,” says Father Pavlos, “he cannot endure stillness.”

Anyone who has tried it knows that solitude is not for the faint-hearted, for as manifested by the immaterial fire of the Burning Bush, God is beyond everything we know. In order to find Him, one must be willing to eclipse the limits of his own understanding, for God is describable only by what He is not – unlimited, inconceivable, ineffable, boundless. Orthodox theology thus looks beyond intellectual contemplation toexperiential knowledge of God, the personal experience of His divine energies. Outside human logic, this is the essence of the life of the monk – indeed of all Christian life – and where unity exists, it can only start here. …

For the complete article, please visit http://www.johnsanidopoulos.com/2015/10/the-ladder-of-heavenly-unity.html#more

“Like a vision of heaven in the wilderness of Moses,” the desert monastics of the Sinai continue to enjoy the peace of mutual respect with the Bedouin tribes with whom they have lived and worked since before the dawn of Islam, in the shadow of the Holy Summit where Moses received the tablets inscribed by the finger of God with the Judaic Law.

In recent years however, due to the humanitarian crises of the Middle East and the crippled Greek economy, the Holy Monastery has lost the financial support elemental to sustaining its role as guardian of this sacred legacy. True to an ethic that says it is better to give than receive, however, the monks maintain their desert tradition of not seeking charity.

Given this situation, Friends of Mount Sinai Monastery (FMSM) was launched in January, 2015 to assist the monks’ efforts to keep the holy tradition of the ancient Monastery alive. An independent 501(c)(3) charity, FMSM is the only IRS-approved nonprofit dedicated to the general support of St. Catherine’s Monastery at Mount Sinai.

His Eminence Archbishop Damianos of Sinai, Pharan, and Raitho has said:

“The great and difficult journey into the desert is something desired by all who value inner peace. Hence, the monks consider the continued operation of the monastery a duty not just to themselves, but to the visitors who reach this wilderness from all corners of the world, hoping to experience the stillness that exists between the soul and God amidst such beauty sanctified by the divine Presence – where the voice of God may still be heard.

“While the Sinai monks have no wish to burden others, even very modest contributions go far in Egypt. Together with the prayers of the faithful, these will sustain the Monastery in the spiritual goals which have rendered it a global symbol of multiculturalism.”