The Monastery of Mt. Sinai, founded in the middle of the 6th century by St. Justinian the Emperor, is one of the main holy places of the Orthodox world. The Burning Bush, from which God spoke to Moses is there, as well as the relics of Great-Martyr Catherine and St. John of the Ladder. Next to the monastery Mt. Horebi, where God gave Moses the Ten Commandments, rises majestically and formidably.

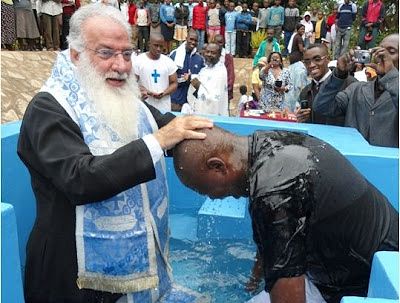

The Monastery of Mt. Sinai has been directed for many years by Vladyka Damian (Samardzis)—a remarkable man, bishop, doctor, theologian, historian, a profound and astute confessor, and an expert and popularizer of Byzantine culture.

Archbishop Damian of Sinai and Pharan

Archbishop Damian of Sinai and Pharan

December 23, 2013, was the 40th anniversary of Damian’s election as Archbishop of Sinai and Pharan. Vladyka graciously agreed to give an interview to the portal Pravoslavie.ru.

“Your Eminenceii, tell us a little about where you grew up.”

“I was born in 1935 in the town of Antalia. It is in the metropolia of Phokida near the Monastery of Osios Lukas. Our family was large: six children—a traditional Greek family for that time. I was the second-oldest child. My parents were pious people—my father sang in church, he was a protopsaltisiii. We observed the fasts in my family, and we loved the church feasts very much.”

Monastery of Osios Lukas

Monastery of Osios Lukas

“Did you decide to become a monk due to the fact that the Monastery of St. Luke was nearby?”

“No, there were other factors here. My spiritual father, Amvrosios Tsatsanis, had a great influence on me. He himself was of the white clergyiv; nevertheless, my love for monasticism comes from him. Not only did the faithful from our own town come to him—the whole metropolia flocked to him. That time—the 1950’s—was difficult: the civil war had ended only relatively recently, and people were in need of spiritual consolation. And he knew how to console and instruct. It was he who directed me towards monasticism.”

“And how did your parents react to your decision?”

“They were not especially enthusiastic about it, of course. They opposed it, but not much. Naturally, they had wanted to see me married. With a family, with children, like everyone else. But they were pious people and, in the end, accepted God’s will for me. In the beginning, however, they tried to talk me out of it: ‘Well, if you finish theological school, what profession will you have, what will you be afterwards?’

‘A priest.’

‘Well, all right.’

I did not tell them then ahead of time that I intended to be an unmarried priest. They wanted to see me become a doctor and at their insistence I attended courses at medical school at the same time as courses at the theological school in Athens and I received a degree as a doctor. Later this proved very useful to me.”

“Tell us about your studies at the University of Athens.”

“I studied there in the late 50’s; I graduated in 1959. It was a very interesting time, when the Zoë Brotherhood and Apostoliki Diakoniav were actively functioning. Catechism lessons were organized—not only for children, but also for adults. I attended classes for catechists, and wanted to become a missionary myself. There was little time—I not only had to study, but also work on the side, and I worked at the publishers of the newspaper “Zoë.” We folded and stacked the newspapers, loaded them into a car, and delivered them. After graduation in 1959 I served for two years in the army, and right after the army I set off for Sinai.”

Dawn on Sinai

Dawn on Sinai

“Why did you decide to choose the monastery at Mt. Sinai, and not Mt. Athos, for example?”

“That’s a good question. The fact is, that when I was serving in the army, in the infantry, Deacon Zakynthios from Mt. Sinai came to my unit in 1960. Bishop Porphyrios III of Mt. Sinai sent him into the army. I became acquainted with him, and he told me about Mt. Sinai, about the monastic life, and also about the fact that the monastery on Sinai is connected with the Patriarchate of Alexandria, which just happened at that time to be carrying on active missionary work in Africa—in Kenya and Uganda. As I have already mentioned, I wanted to become a missionary. That’s precisely why I set off for Sinai. The journey was difficult. There was no taxi—we got there by hitchhiking. And the roads were not like they are now—there were no tunnels. The monastery itself was pretty much closed to visitors. They took me in right away. In April of 1962 they had already tonsured me into monasticism and ordained me a deacon. In 1965 I was ordained to the priesthood.”

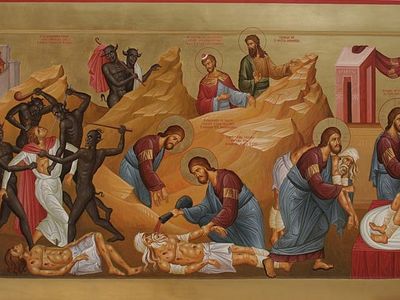

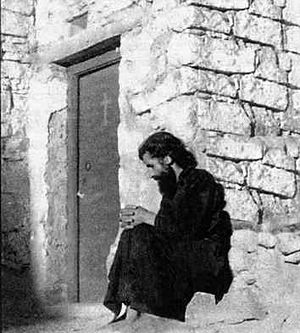

Starets Paisios of the Holy Mountain in the cell of SS. Galaction and Episteme on Sinai

Starets Paisios of the Holy Mountain in the cell of SS. Galaction and Episteme on Sinai

“Yes. I had already become acquainted with him in Greece. Among my friends was Panagiotis Nellas, the author of the well-known book Zōon Theoumenon.vii Once he said to me, “Let’s go to Konitsa. There you will see a holy monk.” We went, and I met Fr. Paisios. My meeting with him produced an indelible impression on me. Later we used to see him on Sinai. My association with him was not only spiritual, but also medical. He had been diagnosed with “pneumonia,” but a whole series of symptoms made me suspect that the matter here was more serious, that we were talking about cancer. And so it was, in the final analysis—Starets Paisios died of cancer of the lungs.”

“Tell us about your life in the monastery.”

“I had to fulfill various obediences in the course of my monastic life. One of the main ones was secretary of the council of elders of the monastery. But that wasn’t the only one. I often had to leave the monastery, among other things to teach in Cairo: I taught theology and history in the monastery school, Abetios. Besides that, I had occasion to work in my second area of specialization—as a doctor in the monastery clinic.viii But in 1970, it seemed that my long-time wish had come true: I was sent to the Orthodox mission in Kenya, where I served until 1971.

The Monastery of Mt. Sinai

The Monastery of Mt. Sinai

“What was your impression of the Orthodox Kenyans?”

“They are remarkable people—simple, open, and giving. When the question arose about the lack of funds for building a church, many people donated the last money that they had, and their valuable possessions, to this end. Of course, I wanted to serve with them longer, but God judged otherwise…”

“How did you spend your monastic life after you returned from Kenya?”

“In rather difficult conditions. In 1971 a fire broke out, which we all extinguished, including Fr. Paul (Vladyka pointed to the elderly monk sitting next to him—note of Deacon V.V.). In 1973 the Arab-Israeli War took place. At the council of the brotherhood on December 23, 1974, they chose me as Archbishop of Sinai and as the abbot of the monastery, but because of the war they did not ordain me right away. The Patriarch of Alexandria came for me and brought me out of the monastery, in order for the Patriarch of Jerusalem, Benedict, to ordain me on neutral territory—at the Mt. Sinai Monastery podvoriyeix in Athens.”

Dawn on Sinai

Dawn on Sinai

“Vladyka, tell us about the Church of Sinai specifically, and about its present status.”

“Originally, until the 7th century, Sinai was in the jurisdiction of the Church of Alexandria and depended on the bishop of Pharan. It’s worth mentioning that Pharan is an ancient Christian settlement, whose inhabitants were originally heathens, but quite early, in the 4th century, they converted to Christianity. The ruins of seven Christian churches along the shore of the Red Sea witness to their Christian life. Since the Sinai Monastery was founded by the holy Emperor Justinian, as an imperial monastery it enjoyed autonomy, its own rule (ustav), and depended on the bishop only when it came to ordaining clergy. But in the 7th century the inhabitants of Pharan, together with the bishop, fled from the Moslems to the protection of the walls of the Sinai Monastery. In addition, the Sinai Monastery received a written document from Mohammed guaranteeing its safety. When the immediate threat had passed, part of the inhabitants of Pharan returned, while part of them settled in at the monastery. Just at that time the abbot of the monastery died, and the brotherhood proposed that the Bishop of Pharan become their abbot. Thus, the monastery acquired virtually full independence. The only problem was the ordination of the bishop himself, whom, however, they choose at the council of the brotherhood—for we have no Synod—but who is ordained by the Patriarch of Jerusalem. At that time, historically, Mt. Sinai Monastery was closely tied with the Patriarchate of Alexandria.”

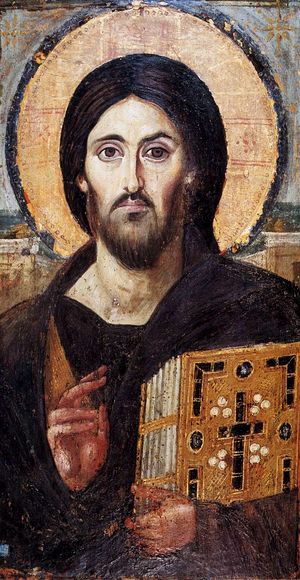

The Lord Pantocrator. Encaustic icon. Sinai

The Lord Pantocrator. Encaustic icon. Sinai

“During this time the monastery has become more open: now a countless number of pilgrims visit it constantly. We try as much as we can to open to the world the spiritual and cultural treasures that the monastery possesses. It is providential that during the restoration of the monastery in 1975, an old library was discovered, with ancient manuscripts of enormous interest to scholars. All in all, thousands of manuscripts in the most diverse languages—Greek, Arabic, Syriac, Georgian, Slavonic, etc.—are kept in the Mt. Sinai library. Unfortunately, because of our limited resources, the library cannot receive all the people who wish to do research here. For this, we must build a new building, for which we do not have the means. The Sinai Monastery owns a collection of ancient icons—one of the most famous of which is the Sinai Saviour of the 6th century. We are trying to open these treasures to the world, and with this aim we are arranging exhibitions, such as, for example, were held in Moscow and St. Petersburg in 2000. I have to say that, given the realities of contemporary bureaucracy, it is an enormous labor: now it takes two years to prepare for an exhibition. In addition we either publish books devoted to the cultural treasures of Mt. Sinai Monastery, or we participate in such publications. At the present moment a book dedicated to the icons of Sinai is being prepared in Moscow, edited by Professor A.M. Lidov.

But that is only one side of things. Another is connected to the restoration of the churches on the territory of Sinai, and also to the restoration and support of the monastery’s podvoria in Greece (on the islands of Zakynthos and Crete), Egypt, and Turkey. We have our gardens and vegetable gardens. It’s another matter, that, according to the Church canons, we cannot sell anything from them—on the contrary, they themselves require the investment of resources, which is becoming more and more problematic, considering the present crisis.

The Podvoriye of the Mt. Sinai Monastery on the Island of Zakynthos. Photo: K. Turikis

The Podvoriye of the Mt. Sinai Monastery on the Island of Zakynthos. Photo: K. Turikis

The next aspect of our activity is charity. Two-thirds of our expenses go towards charitable ends, which are both a clinic for Bedouins and a school for them. It’s worthy of note that several of the Bedouins who went to our school have graduated from Cairo University. As to the clinic, we attract qualified specialists from Greece, which is very important for the Bedouins. Dental help is especially important for them, since they often experience protein insufficiency. Right now troubles have also arisen with the financing of this important activity. The Greek government has almost stopped helping us because of the crisis. As the Turks say, “Deneg iok.”x Pilgrims give us the principal source of our funds.

We give the neighboring Bedouins direct financial support also because they live in terrible poverty. In so doing, we try to provide them with work relating to pilgrimages and tourism. For example, Fr. Moses, one of our brothers, was able to organize the production of textiles and clothes for tourists, and also leather goods, which sell out and bring the Bedouins a certain income. But setting up production also requires investments.”

“Dear Vladyko, the acute question of Moslem radicalism and extremism is arising in the world now. What experience do you have from coexisting with the Moslems?”

Vladyka Damian conversing with Bedouins

Vladyka Damian conversing with Bedouins

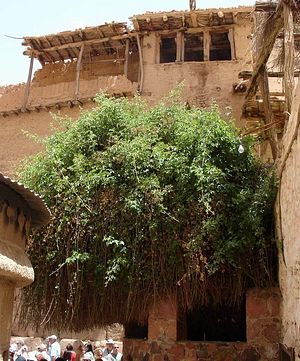

The Burning Bush

The Burning Bush

“Of course, thanks to St. Catherine, a great number of miracles occur. For example, when her relics are brought out for veneration, many people smell a subtle fragrance. A great number of healings have come from her holy relics, including terminal illnesses such as cancer. Once a lady from Greece travelled to the monastery. They had diagnosed cancer in her. After she had prayed, she kissed the Saint’s relics. When this lady returned to Greece, she went to the very best diagnostic centers, where they could not find any traces of cancer.

St. Catherine has saved drivers on the road who are of the faithful. One driver told me about how an oncoming car had crossed into his lane and was rushing straight towards him. He had just managed to cry out, “St. Catherine, help!” when by some miracle he avoided the collision.

Moslem women often come to us, who are possessed by unclean spirits, and they receive healing from the relics of St. Catherine. And here we see nothing inappropriate in showing them spiritual help—the Holy Apostles healed heathens, too, you know.

However, the most important miracle is the transfiguration of the human soul, when Christ comes to dwell in it and miraculously changes it and makes it like Himself. Take the Ladder of St. John of the Ladder, for example: what he says is equivalent to Holy Scripture.

Archbishop Damian of Sinai and Pharan

Archbishop Damian of Sinai and Pharan

“First, I would like to thank the Russian pilgrims for their prayers and sacrifice, when people who are often of very modest means donate so much to the monastery.

Second, we look forward to seeing you and would be glad if you came to visit us.

Third, keep Orthodoxy, for in Christianity it is the only truth and the only chance for the salvation of the world which has gone astray.

Fourth, think about your own soul, for its cleansing and salvation. In Christ a man receives more than he lost in Adam, for the Kingdom of Heaven that Christ gives us is higher than the earthly paradise of Adam. But then let us think about what kind of purity a man must acquire in order to enter into this Kingdom. Let us not put off our salvation till later, nor hope that we will be purified before death or even at the time of death, or that we will land in “purgatory,” as the Catholics mistakenly think. For those who say, “Later,” it will never come. Therefore let us be concerned about our salvation now, while it is still possible to say, “Now.”

Deacon Vladimir Vasilik interviewed

Archbishop Damian of Sinai and Pharan

December 26, 2013

Translated by Dimitra Dwelley

i Another name for Mt. Sinai

ii In Russian: “Your High-All-Holiness” Vysokopreosvyaschenstvo (—Trans.)

iii Protopsaltis—in Greece, a lead cantor/chanter who may do solos and lead the choir

iv i.e., a married priest, not a priest-monk

v the Zoë (Greek: Life) Brotherhood and Apostoliki Diakonia (Greek: Apostolic Service). The latter is a missionary society under the direct authority of the Holy Synod of the Orthodox Church of Greece, coordinating various church organizations.—Orthodox Encyclopedia

vi Starets = “Elder”

vii: “Being Deified.” The English translation of this book is entitled: Deification in Christ: Orthodox Perspective on the Nature of the Human Person. trans. Norman Russell (Crestwood NY: t. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1987).

viii [Footnote in original Russian article:] Vladyka, in his humility, is silent about the fact that it was he himself who organized the first clinic in the history of the monastery for helping Bedouins, and he worked in it for 20 years as a doctor.

ix Podvoriye—A church (and/or monastic property) owned by a monastery located in some other city, which represents that monastery.

x “There is no money.” The original used the Russian word deneg (money—gen. pl.) and the Turkish word ɪok = “there is no.”