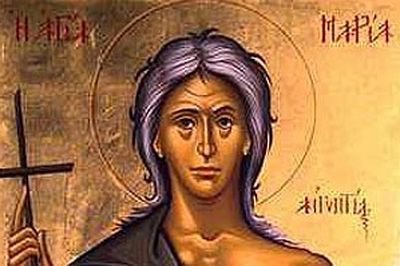

The Life of St. Mary of Egypt is one of the ascetical treasures of the Orthodox Church, which helps us understand God’s plan for salvation. Like everything that is outside of time, the Life of the Egyptian desert-dweller is contemporary in the true sense of the word—every living soul can recognize its own experience in St. Mary’s experience; the Life of the saint both rebukes and heals.

* * *

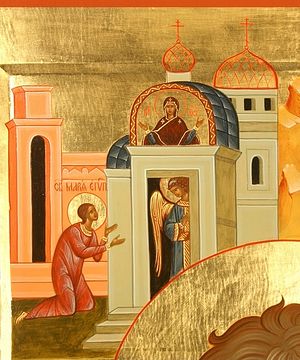

St. Mary crosses the Jordan.

St. Mary crosses the Jordan. The desert is a place of trust, and not surety. There is no guarantee here. How many of the Israelites who followed Moses actually saw the earthly paradise?

Faith, or belief, is discomfort, pain, light, and joy. Having faith (believing) means walking on water.

* * *

Why did the Lord call Mary to repentance in such an unexpected manner? Does this mean that there are on this earth special people chosen by heaven, for whom the path of salvation and illumination are prepared, and that if you don’t belong to their category then there is no point in fleeing your enslavement?

If we suppose that the Creator divided his children from the beginning (not just creatures, but children) into the loved and not loved, then we turn ourselves into marionettes, and the Last Judgment promised in the Gospels is cancelled. The simplest justification for a sinner is, “I was not chosen for salvation, You did not give me the possibility to rise from my knees, so how can I now converse with angels?”

Fatalism says that the Lord gave Mary strength, and therefore the harlot became an angel. First grace, and then labors. But we see it differently. On the earth, time moves from the past to the future, but in heaven there is no past, nor future. Therefore the Lord gives special grace to the one whom His foreknowledge discerns to be a laborer of the spirit. First labors, and then grace. It is a paradox of reverse time.

If a music teacher were clairvoyant and knew how his students would make use of his lessons, he would give more attention to those who truly dedicated themselves to any work and who would in the future “serve the muses.”

First (if we can say it this way) the Lord saw Mary, who lived in the desert like an angel, and only then as a harlot.

First the Lord saw Mary’s martyrdom in the desert, her absolute dedication to the revealed Truth. Only for that reason was she given such grace.

If a person is ready, like Mary, to wither from heat, nearly die from the cold, starve the body, and war to the utmost with the passions, then the Lord reveals His love, strength, and glory to that person.

* * *

The word “sin” translated from the Greek means, “missing the mark”. A sinful person is one who directs the God-given strengths of his soul to the wrong aims. Thus, discernment that misses its goal becomes judgment, a sense of one’s own dignity becomes pride, and emotions become anger.

St. Mary of Egypt received from the Lord the gift of fiery, unquenchable love, and instead of giving her heart to her Creator and His creation, she directed all the force of divine eros on herself. But any talent directed exclusively towards our “Me” not only impoverishes a person—it deprives him of his sanity.

“He was out of his mind” is how the Church hymn describes another gifted egotist—the prodigal son.

When Mary finds herself in Jerusalem, her love returns to its natural course. For the sake of love for the Lord the desert-dweller who had sinned inhumanly accepts the podvig of inhuman asceticism and struggles for seventeen years with cold and heat, hunger and demonic thoughts.

* * *

I don’t know about you, but I believe in the sincerity of Mary’s first repentance; I think that she could have changed her life, gotten married, had children, and become an exemplary Christian. But why does the Lord Whom she trusts lead her to the desert? Weren’t her tears enough? Couldn’t the Lord just forgive her right away? He can. Abba Sisoes was asked the same question: “If a brother falls, is one year of repentance enough for him?” He answered: “Those are cruel words!” “Are six months enough?” he was asked again. “Too many,” the elder answered. They asked again, “Are forty days enough?” “That is also too much,” he answered. “Then how many?” they said. “If a brother falls and a supper of love [the Eucharist.—Trans.] is soon held, can he come to the supper?” “No,” the elder answered,” he must spend several days in repentance. And I believe that if he repents with all his soul, then God will receive him in three days” (Memorable stories about the ascetic labors of the saints and blessed fathers).

The Life emphasizes that repentance is an ontological event, and not one of ethics. The penitent is redeemed, and now he needs healing of his nature and sanctification.

How often does a newly-converted sectarian feel pleased with himself that he has given up fornicating or drinking. For the Orthodox this is only the beginning, the first step. After that, grace allows him to see his own imperfection. The person enters into a fight to the death with his own self, disclosing more and more new passions.

Thus, in a low-lit room everything seems clean, but when the light is turned on the picture is different—the housekeeper notices every speck of dust. If sectarians knew God and had an authentic experience of grace, they would never stop on the path of repentance.

Here is another analogy: Our own imperfection is clearly seen when coming closer to the center. The top musician of St. Louis gets third place in Chicago, fifth in New York, and seventh in Paris. Why would a woman with so many affirmations that she has been forgiven by God (she walks on water, has the gift of clairvoyance, etc.) sincerely consider herself the worst sinner? Because she was approaching the Center, and was illumined by an unutterable light.

* * *

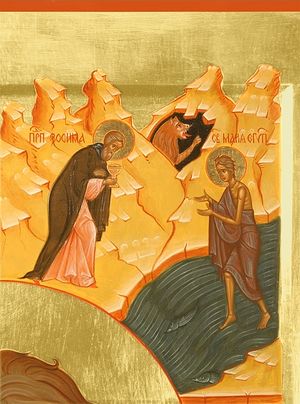

The saint leaves the world and there, in the desert, far from the noisy cities and solitary monasteries, she has her first connection with other people. “What is taking place in the empire?” the desert-dweller asks Abba Zosima. Seventeen years ago she was interested only in her body. Now Mary knows that there are other people.

* * *

Repentance is an ontological event, and not one of ethics. Therefore in the sacrament of confession of sins not only is the soul transformed, but also the body.

Here is the recollection of one nun, a spiritual daughter of Fr. Ambrose [of Optina], of how she once confessed in the elder’s cell: “In his cell burned votive lamps and a small wax candle on the table. It was too dark for me to read from a list [of sins], and I had no time. I said what I remembered, and that hastily, then added, ‘Batiushka, what else can I say to you? What should I repent about? I’ve forgotten.’ The elder criticized me for that. But suddenly he rose from his bed where he was lying down. Having made three steps, he found himself in the middle of his cell. I involuntarily turned after him on my knees. The elder straightened to his full height, raised his head and hands upward as if in a prayer position. It seemed to me at the time that his feet left the floor. I looked at his illumined head and face. I remember that the ceiling in the cell was as if gone, it parted, and the elder’s head was as if thrust upwards through it. This appeared very clearly to me. A minute later, batiushka leaned over me, astounded at the vision as I was, and making the sign of the cross over me said these words: ‘Remember, this is what repentance can lead to. Now go.’ I left him, staggering, and wept the whole night through about my stupidity and carelessness. In the morning we were given horses and we left. While the elder was still alive I couldn’t tell anyone about this. He forbade me once and for all to talk about such incidents, threatening, ‘Otherwise you will lose my help and grace’” (from the Life of St. Ambrose of Optina).

The repentant sinner not only receives the gift of clairvoyance, but also walks on water.

Believing means walking on water.