SOURCE: The Victorian Web

Philip V. Allingham, Contributing Editor, The Victorian Web; Faculty of Education, Lakehead University, Thunder Bay, Ontario

Nearer and closer to our hearts be the Christmas spirit,which is the spirit of active usefulness, perseverance, cheerful discharge of duty, kindness and forbearance! — Charles Dickens, "What Christmas Is as We Grow Older," 1851

As we look back from our perspective of a century-and-a-half, Charles John Huffam Dickens does indeed seem to be what London's Sunday Telegraph for 18 December 1988 proclaimed him, "The Man Who Invented Christmas." Certainly, he seems to have convinced his younger contemporaries that it was he rather than Benjamin Disraeli's Young England Movement or Oxford's Puseyites that had rediscovered the great Christian festival that — because of the massive inmigration to the cities that accompanied the industrial revolution — had been on the wane in Great Britain since the latter part of the eighteenth century. Paul Davis in The Lives and Times of Ebenezer Scrooge (1990) retells the anecdote first told of Dickens by Theodore Watts-Dunton in 1870. As he was walking down Drury Lane near Covent Garden Market on June 9th that year, Dunton overheard a Cockney barrow-girl's reaction to the news of the great novelist's death: "Dickens dead? Then will Father Christmas die too?" The fact is that, for those of us of British origin, Dickens more than anybody else revived the Christmas traditions which had nearly died out.

Although Dickens celebrated the festival of Christ's birth in numerous works, it is A Christmas Carol, published on 19 December 1843, that has preserved the Christmas customs of olde England and fixed our image of the holiday season as one of wind, ice, and snow without, and smoking bishop, piping hot turkey, and family cheer within. Coming from a family large but not-too-well-off, Charles Dickens presents again and again his idealised memory of a Christmas associated with the gathering of the family which "bound together all our home enjoyments, affections and hopes" in games such as Snap Dragon and Blind Man's Buff, both of which his model lower-middle-class father, Bob Cratchit, runs home to play on Christmas Eve.

Dickens's most recent biographer, Peter Ackroyd, notes that our image of a snowy Victorian Christmas is a mere accident of history. Although eastern England has a winter climate somewhat more raw than that of Vancouver, British Columbia, Portland, Oregon, or Seattle, Washington, it is by no means as chilly and bleak as Dickens depicts it. "In view of the fact that Dickens can be said to have almost singlehandedly created the modern idea of Christmas, it is interesting to note that in fact during the first eight years of his life there was a white Christmas every year; so sometimes does reality actually exist before the idealised image" (p. 34). Ackroyd points out that Dickens' boyhood Christmases were probably inspired by his father, John Dickens, who until his nineteenth year would have celebrated the season with his parents, butler and maid at the opulent Crewe Hall, where he would have participated with servants and tenants in conjurings, country dances such as Sir Roger de Coverley (footed by Mr. and Mrs. Fezziwig among their apprentices and employees in Scrooge's youth), forfeits, Blind Man's Bluff, and card games such as Speculation. Owing to the fear of drinking contaminated water, various kinds of gin punch such as Purl (beer heated to near-boiling, then flavoured with gin, sugar, and ginger) and Bishop (heated red wine, oranges, sugar, and spices) were consumed by revellers of all ages, again as in the festivities in the Cratchit household.

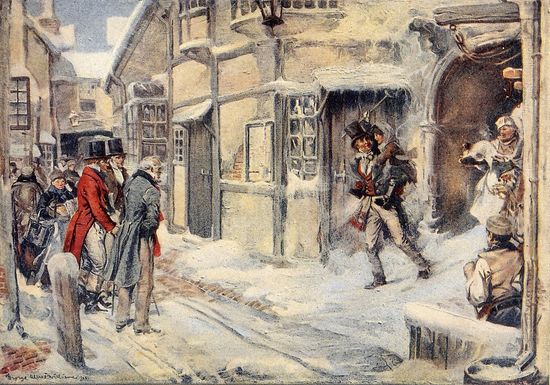

This all sounds very much like the traditional Victorian Christmas that the British Post Office recalled in a series of five postage stamps marking the 150th anniversary of the publication of A Christmas Carol. As the commemorative stamp packet points out, by the beginning of the nineteenth century the old ceremonies and festivities had become obsolete because, as the poet Robert Southey remarked in 1807, "In large towns the population is continually shifting; a new settler neither continues the customs of his own province in a place where they would be strange, nor adopts those which he finds, because they are strange to him, and thus all local differences are wearing out." Both Sir Walter Scott in 1808 and Washington Irving in 1820 had likewise lamented the passing of the old 'country' Christmas of twelve days of jollity and misrule. By the beginning of the Railway Age in the 1840s many people approaching middle age (as Dickens then was) began to look back nostalgically to the good, old days of coaches and hospitable inns, manorial feasts, and blazing yule-logs. However, Britain was also in need of new Christmas traditions as, for the first time in its history, it had become a nation of urbanites who could hardly afford to take off the twelve days that had constituted the holiday season for their rustic forebears. Enter Charles Dickens... and others.

The Victorian imagination eagerly seized upon William Sandys' Selection of Christmas Carols, Ancient and Modern (1833) and Thomas K. Hervey's detailed accounts of Christmas traditions in The Book of Christmas (1837). The Christmas tree, which Dickens termed "that pretty German toy" in his 1850 Christmas essay for his journal Household Words, is not yet a feature of the typical middle-class English Christmas in the 1843 novella. Likely, it was introduced into England by Queen Victoria's consort in December, 1840, the couple having been married just the previous February. The tree, lit by candles still in European countries, complemented the holly and mistletoe that the Anglo-Saxons ever since their arrival in Britain in the fifth century had used to decorate their homes at the mid-winter festival. Before Prince Albert Edward's innovation, better-off English homes had used the "kissing bough" as the main decoration for the season. Two hoops were joined to make a globe, decorated with greenery, oranges, and apples, and, of course, mistletoe.

Christmas cards, coincidentally, originated in the early 1840s also, no particular thanks to either Charles Dickens or Prince Albert. In 1843, town aristocrat Sir Henry Cole, always too busy to write proper letters to his friends at Christmas time, commissioned John Calcott Horsley of the Royal Academy of Arts to develop a decorated hasty-note. Having had a thousand printed, Cole sent the numerous leftovers to be sold at a stationer's shop in Old Bond Street, London. The idea was slow to catch on, however; not until the 1880s did the general production of commercial Christmas cards begin in England.

The Christmas cards we send each other bear mute testimony to the pervasive influence of the Dickensian Christmas, as if our cultural notion of the holiday is permanently arrested in the early 1830s in rural England, when Dickens, then just a cub reporter for the True London Sun was racing around the countryside covering political events. Christmas was never far away for Dickens at any stage of his life; it is there in his first book, The Pickwick Papers (which contains the prototype of A Christmas Carol, "The Story of the Goblins Who Stole a Sexton," the curmudgeon being the delightfully named Gabriel Grubb) and somewhat more gloomily in his last,The Mystery of Edwin Drood. For Dickens each year the deadline came for his Christmas story in either his weekly magazine Household Words (20 March,1850-28 May, 1859) or its successor All the Year Round, something he ruefully called clearing "the Christmas stone out of the road." Despite critical and even evangelical disapproval of the Christmas Books (Dec., 1843-Dec., 1848), Dickens might have gone on grinding out such "Somethings for Christmas" the rest of his life, as far as the general reading public was concerned. Even the gloomy Haunted Man, the last of the series, with its scarlet binding and abundant illustrations, sold 18,000 copies on its day of publication.

However, Dickens's founding and managing his weekly literary magazines seems to have prevented his producing further complete books exclusively for the Christmas book trade (which he in large measure helped to establish with Carol and its successor, The Chimes). Instead, he developed 'framed tales' in which he would take the lead supported in the production of various chapters by such talented writers as Wilkie Collins and Elizabeth Gaskell. These 'Christmas Stories' were composed between 1850 and 1867, but cannot be classified as falling within a single short fiction subgenre. Dickens's first contribution to an 'Extra Christmas Number' was in fact not a story at all, but a reverie, "A Christmas Tree" (HW1850) inspired by children gathered around that German innovation, the Christmas tree (which never appears in any of the Christmas Books), probably brought to England by Victoria's consort, Prince Albert, whom she had married in 1840. Dickens's second and third short-fiction Christmas offerings, "The Poor Relation's Story" and "The Child's Story" (HW1852) are his contributions to A Round of Stories by the Christmas Fire in the Christmas Number of Household Words(1852). As one reads these "framed tales" it becomes increasingly difficult to sort out which pieces Dickens contributed, especially since all pieces printed in these two journals were unsigned. In 1853, Dickens contributed "The Schoolboy's Story" and "Nobody's Story" to Another Round of Stories by the Christmas Fire in the Christmas Number for Household Words. Other Christmas Stories include The Seven Poor Travellers in the Christmas Number for Household Words (14 Dec., 1854), The Holly-tree Inn (the Christmas Number for Household Words, 15 Dec., 1855), The Wreck of the 'Golden Mary' (the Christmas Number of Household Words, 6 Dec., 1856), The Perils of Certain English Prisoners (the Christmas Number for Household Words, 1857), A House to Let (the Christmas Number for Household Words, 1858), The Haunted House (the Christmas Number for All the Year Round, 1859), A Message from the Sea (the Christmas Number for All the Year Round, 1860), Tom Tiddler's Ground (the Christmas Number for All the Year Round, 1861), Somebody's Luggage (the Christmas Number for All the Year Round, 1862), Mrs. Lirriper's Lodgings (the Christmas Number of All the Year Round, 1863), Mrs. Lirriper's Legacy (the Christmas Number of All the Year Round, 1864), Doctor Marigold's Prescriptions (the Christmas Number of All the Year Round, 1865), Mugby Junction (the Christmas Number for All the Year Round, 1866), and the Collins-dominated No Thoroughfare (the Christmas Number for All the Year Round, 1867).

Thanks to modern methods of poultry raising as much as to Dickens, that American import, the turkey, began to replace the traditional (bony and greasy) goose as the centrepiece of the Christmas board, as is evident in A Christmas Carol, but the survival of the Christmas pudding abroad owes much to Dickens' image of the Cratchits' pudding singing in the copper. The "jolly Giant, glorious to see" in the Third Stave of A Christmas Carol is the earliest English version of the German Santa Klaus, but in John Leech's coloured illustration he is garbed in green, a pagan vegetation symbol as much as modern English "Father Christmas" accompanied by such pre-Christian paraphernalia as a crown of holly, a flaming link (torch), a yule log, mistletoe, and a steaming bowl of negus (punch). Our North American Santa Claus was invented just twenty years earlier, in Clement C. Moore's A Visit from Saint Nicholas, derived not from the old Roman god Saturn (whose worship from December 17th to 24th had included decorated tree boughs) like Dickens's Ghost of Christmas Present, but from the gift-giving early Christian bishop and saint from Asia Minor.

One of his sons wrote that, for Dickens, Christmas was "a great time, a really jovial time, and my father was always at his best, a splendid host, bright and jolly as a boy and throwing his heart and soul into everything that was going on.... And then the dance! There was no stopping him!" Amateur magician and actor, Dickens had little Christmas shopping to worry about, and no crowded malls or crass commercialization of the family festival to jangle his finely-tuned nerves. But that time in his boyhood, when he slaved in the blacking factory while his family were in the Marshalsea Prison, weighed heavily somewhere in the back of his mind, and made occasional intrusions, such as Ignorance and Want in A Christmas Carol and the street urchin in The Haunted Man.