The Dormition Cathedral

The Dormition Cathedral

When I learned that among the bishops serving at the Dormition Cathedral would be Bishop Arseny of Serpukhov , someone with whom I was acquainted, I asked his subdeacon, Hierodeacon Fr. Joasaph, to help me get into the Dormition Cathedral for the Anathema service.

Kind Fr. Joasaph said, "Nothing could be easier. Come to me on Sunday, and I will give you Vladyka's miter case , and we will go to the Cathedral together."

At the appointed time, I came to see Fr. Joasaph in the Chudov Monastery (later demolished after the Revolution) , and we went together to the Dormition Cathedral, which was but a three minute walk [from the Chudov Monastery.]

It was a warm day, on the threshold of springtime. The sun shone dully through a thin layer of clouds. Dirty yellowish-brownish snow was already melting, and murky streams were running along the sidewalks and noisily pouring out into the storm sewers. The air was gentle, humid, and filled with the smell of slushy melting snow. From the Ivan the Great bell-tower, the great bell droned, vibrating the air with its velvet, thick, brazen tongue, and causing my chest to shiver. …

The area before the Western gates of the Cathedral was absolutely black with people. Among them would briefly flash the black and orange piping on the overcoats of the municipal police, and the grey-blue overcoats of the police officers. The crowd pulled me away from Fr. Joasaph even before I had gotten to the Cathedral doors. At that time, the members of the Synodal choir were going in, two at a time. I followed along with them, but the policeman stopped me.

«You can't go in,» he said, barring my way. "The Cathedral is filled to overflowing. Young man, be so kind as to go to a different church."

"But I am carrying Bishop Arseny's miter," I replied, and showed him the miter carrying case.

"Ah, then go on in. The young man with the miter is to be allowed to pass," he ordered the municipal policeman who was standing directly before the Cathedral doors.

With some difficulty, I somehow pushed my way through the crowd filling the Cathedral, and into the chapel on the left, and from there got into the Altar. There was a multitude of clergy getting ready to meet the bishops.

I was lost among the crowds of deacons, subdeacons, archpriests and archimandrites. Protodeacon Rozov, renowned throughout Russia , a handsome rosy-cheeked knight in a gold brocade, seemingly forged [and not woven] sticharion, was softly explaining something to one of the archimandrites in a mantya. At that moment, Fr. Joasaph approached me, took the case from me, and led me to a small archway connecting the Altar with a dark passageway, poorly illuminated, with a window with an elaborate grill, and round mica-covered windows. It was there that the Synodal choir members were putting on their festal caftans of purple velvet and gold, caftans whose cut was reminiscent of boyar attire, with high collars, quite different from those worn by ordinary Russian church choirs, kuntush caftans modeled on 17th Century Polish-Ukrainian style.

From the crowd filling the church came a restrained dull roar. The powerful toll of the bell in the Ivan the Name Great Type Tower merged into the general rumbling sound. The sun's dull rays penetrated into the Altar, piercing through the aromatic, blue smoke coming from the censers.

Here two subdeacons in gold brocade sticharia with oraria belted cross-wise around them, pulled back the heavy, silk curtain - whose supporting rings made a faint ringing sound as they moved along the rod - and immediately opened the low, wide Royal Doors. The crowd quieted down. One could hear the quiet tinkling of bells on the bishop's mantiya. Bishop Dimitry of Mozhaisk, one of the celebrants, entered the Altar. The Royal Doors again closed… The bell from the Ivan the Great continued its drone.

Soon, Bishop Arseny of Serpukhov and Bishop Modest of Verei were greeted in the same way. But suddenly, the sound of the great bell was joined by a multitude of harmonics, as the festal «trezvon» peal sounded out.

The clergy (except for the bishops) began to leave the Altar through the side [deacon's] doors to meet Archbishop Vladimir of the Don and Novocherkassy, who was to be the principal celebrant. The trezvon ceased. The crowd buzzed almost imperceptibly. At the entrance, the rattling rumble of the mantiya bells was joined by the gentle ringing sound of censers being swung by the deacons.

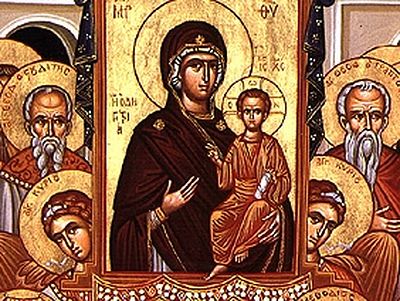

And then, in the midst of the quiet that had suddenly descended, Protodeacon Rozov's deep but gentle basso sounded out – not loudly, but filling the entire church: "Wisdom…" And then, even more quietly, in an even lower register, in a quiet rumbling, conversational tone: "It is truly meet to bless thee O Theotokos…"

It was as if a breeze had moved through the ancient cathedral, like unto the sound of distant waters, or the sound of approaching rain. Very quietly, from both kliroses, the assembled Synodal choir began to sing the opening "It is truly meet…" The pure steady voices of the young boys, the silvery treble, the coppery altos, the fluttery tenors, the melodious baritones and velvety profoundly low bassos merged into one powerful yet soft and marvelous choir, whose sound filled the entire cathedral.

And that cathedral held memories of the Great Princes of Moscow, of those who had assembled the lands that make up Russia , of the early Tsars, the Emperors, the Metropolitans and Patriarchs. By turns, the choir's voice would build, and once again become hushed.

Although by then I was hard to amaze, I was staggered by this singing. I had already heard the famous choirs of Moscow and St. Petersburg and Kiev , and had witnessed hierarchical services in great cathedrals. But I had never heard anything like this. In that moment, I acutely felt the whole inexpressible beauty of what surrounded me, into just what my whole being was immersed at that moment. I understood the solidity of the whole: the ancient cathedral with its massive round columns, decorated with stern frescoes and stretching upward, and the Altar, bright with gold, and the aromatic smell of incense, the gold vestments worn by the clergy, and the marvelous chant, and the pious sound of the crowds of people; the words of sacred chant, the signs of the Cross devoutly made by the faithful — all these were inseparable parts of one unity, connected to one another in one marvelous whole….

And suddenly a loud and festive chord sung by the entire choir rang out: "Ton despotin, kai arkhierei imon," and from the ambo, the bishop was blessing the people. The vesting of the bishops began. The concelebrating bishops were vested in the Altar. The choir sang, "Thy soul shall rejoice in the Lord," but not the L'vov setting that calloused the ears, but rather another setting (by Balakirev, I believe) that I had not heard before. I marveled at the structured, measured, symmetrically synchronized movements of the subdeacons vesting the bishops. And again, in them as well, one sensed the traditions that had been established over the centuries, something inexpressible in words, the centuries-old tradition of our pious fathers. It was expressed in everything: in the movements of the clergy, and in how the people stood in church, and in how and what the choir sang. One had the sensation that here the best of the best had been assembled. Yes, this is unforgettable, and blessed is he who has seen and heard that beauty. Such glory and beauty no longer exists upon the earth!...

The reading of the Hours came to an end. The Rite of Orthodoxy began. The bishops and all of the clergy came out of the Altar. The bishops took their places on an enormous hierarchical ambo, covered with scarlet cloth, in the middle of the church. The mass of clergy, with icons in their hands, stood in two rows stretching almost to the Royal Doors themselves.

And so the solemn rite of prayer approached its conclusion. Protodeacon Rozov ascended to an analogion set upon a specially-installed dais at the front left column. Everyone's attention turned to Rozov.

Protodeacon Rozov

Protodeacon Rozov

But how he read it! Although he did not sing it, he imparted to every single word particular power and expressiveness. I was amazed at how he accomplished such expressiveness, without relying on some kind of "declaiming" "oratorical" or "theatrical" effects. He spoke so simply, as if in persuasive conversation with someone, and so triumphantly, but without the slightest hint of dramatic effects, something so dangerous to fall into when engaging in "declamatory recitation." No wonder that Rozov was famous in Russia as an artist-protodeacon, not only thanks to his unique voice, but thanks to his ability to use it.

"This is the true Faith,

This is the Faith of the Apostles,

This is the Orthodox Faith,

This Faith established the universe,"

Thus, Rozov sang to the melody of the ancient chant, after he had read the Symbol of Faith. Then he read how the Church maintained the Faith and Tradition of the Holy Fathers, and how those who believe otherwise it separates from itself …(and there, changing to a somewhat lower pitch, Rozov said slowly and deliberately) "…and a-na-the-ma-ti-zes!"

Then, in a yet deeper voice, he begins the «recitation» of the anathema:

"All those who deny the existence of God, and assert that the world came into being by itself - Anathema!

«Anathema! Anathema! Anathema!» — in an awesome unison the entire mass of clergy, the vast majority of whom were bassos, sang in reply.

The Synodal Choir took up and echoed the chant, "Anathema, Anathema, Anathema!"

Once again, Rozov «exclaimed» a new separation – and in response the awesome "anathema" thundered from the clergy and choir.

The faces of the holy martyrs looked out sternly from the frescoes on the tall columns. Sternly and solemnly, in all the glory of Orthodoxy the bishops stood, vested in gold sakkoses that looked as if they had been forged [rather than woven].

The Church's awesome power to bind and loose was palpable. Those proclaimed anathemas, which year in and year out had thundered from within the confines of these arches, were terrifying and awesome.

Were those anathemas, as many suppose, condemnations? No. In a condemnation there is hatred, and a desire for revenge and destruction. Here, though, is what was being clearly confessed: The Church did not condemn, but simply separated from its midst those who did not see themselves as belonging to it, those who refused to accept its teachings. Those who do not believe as the Church teaches, are separated from it, are alien to it, are "anathema," "set aside," but they can always be received again, should they recognize their error and return to Orthodox teachings. It is not so much that the Church separates them from itself, as that they themselves had set themselves apart from the Church, and now the Church solemnly announces that fact.

The pronouncing of anathemas came to an end. Rozov began to read how the Church glorified and kept and honored the memory of those who have defended and preserved the Orthodox Faith. And now, soft gentle sounds move through the Church: "In a blessing falling asleep, grant O Lord, eternal rest…" How amazed I was to hear "…to the Equal-to-the-Apostles Tsar Constantine … Justinian the Great…Theodosius the Great, Theodosius the Younger… the Equal-to-the-Apostles Prince Vladimir…Tsar Ioann Vasilievitch, Tsar Alexey Mikhailovitch…Emperor Alexander III…"

In that commemoration, I realized that in the consciousness of the Church, all of the generations of Orthodox people - not only those living now, but also those who had died long ago - lived. In that "memory eternal" which immediately followed the anathemas, and which was sung for those to whom we serve Molebens as well as for those for whom we serve Panikhidas, was expressed the totality, the sobornost' [conciliarity], and the universality, the omnipresence, of all of the generations of the entire faithful Orthodox people.

And after the "memory eternal" had been proclaimed, there followed the usual thundering "many years" for the Sovereign Emperor and the other Orthodox ruling figures, for the Orthodox Patriarchs – of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem, for the authorities, and for all Orthodox Christians.

The Choir festively sang Kastalsky's marvelous «many years,» which is in such an ancient Russian mold, and which is so loved in Moscow .

At the singing of the Te Deum, "We praise Thee, O God," Archbishop Vladimir and the other hierarchs processed into the Altar. As his legs were not well, [Archbishop Vladimir] did not serve the Liturgy. It was served by Bishop Modest, assisted by the other hierarchs.

And here again I was amazed at the art of the Synodal Choir: They sang "We praise Thee O God" not as a concert piece, but in the simple Moscow setting of the 3rd Tone, antiphonally, alternating between two kliroses. Yet how festive was the Synodal Choir's rendition of that hymn! Barely perceptible emphases, and the choir's wonderfully expressive diction turned that primitively simple and continually repetitive melody into a real artistic composition, far more expressive, festive and powerful, than the loud and pathos-filled Bortniansky concert piece that is used everywhere. Since then, whenever I hear that piece by Bortniansky, there creeps into my soul a longing for the Synodal Choir's "Thee O God we glorify," in that ordinary, most simple Moscow third tone, but… with the Moscow Synodal Choir's diction!

The solemn Rite of Orthodoxy in Moscow 's Dormition Cathedral made an enormous impression upon me, one that has remained with me all of my life. Both before and since, I have attended solemn, festive church services in a variety of places, and have listened to some very good choirs. However, in terms of how great an impression was made upon me, the service I have described has remained for me the most memorable, and is still unforgettable. Now, half a century later, I can confidently state that [at that service] I took a deep breath of what is Russian Orthodox Church Tradition and Name Russian Type Church culture. They cannot be learned from books or accounts; it is in their fullness that they can be grasped.