September 23, 2014

Archaeologists in Israel have discovered the remains of a Byzantine-era compound near Jerusalem. They believed it is to have once been a monastery and includes an oil press, wine press and mosaics.

An archaeological survey conducted on foot along the hills south of the town of Bet Shemesh brought to light remarkable finds. During the survey blocked cisterns, a cave opening and the tops of several walls were visible on the surface. These clues to the world hidden underground resulted in an extensive archaeological excavation there that exposed prosperous life dating to the Byzantine period which was previously unknown.

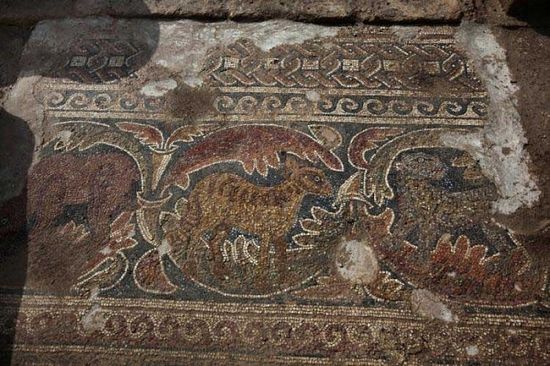

The compound is surrounded by an outer wall and is divided on the inside into two regions: an industrial area and an activity and residential area. An unusually large press in a rare state of preservation that was used to produce olive oil was exposed in the industrial area. A large wine press revealed outside the built compound consisted of two treading floors from which the grape must flowed to a large collecting vat. The finds revealed in the excavation indicate the local residents were engaged in wine and olive oil production for their livelihood. The impressive size of the agricultural installations shows that these facilities were used for production on an industrial-scale rather than just for domestic use. In the residential portion of the compound several rooms were exposed, some of which had a mosaic pavement preserved in them. Part of a colourful mosaic was exposed in one room where there was apparently a staircase that led to a second floor that was not preserved. In the adjacent room another multi-coloured mosaic was preserved that was adorned with a cluster of grapes surrounded by flowers set within a geometric frame. Two entire ovens used for baking were also exposed in the compound.

According to Irene Zilberbod and Tehila libman, excavation directors on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority, “We believe this is the site of a monastery from the Byzantine period. It is true we did not find a church at the site or an inscription or any other unequivocal evidence of religious worship; nevertheless, the impressive construction, the dating to the Byzantine period, the magnificent mosaic floors, window and roof tile artifacts, as well as the agricultural-industrial installations inside the dwelling compound are all known to us from numerous other contemporary monasteries. Thus it is possible to reconstruct a scenario in which monks resided in a monastery that they established, made their living from the agricultural installations and dwelled in the rooms and carried out their religious activities.”

At some point, which we date to the beginning of the Islamic period (seventh century CE), the compound ceased to function and was subsequently occupied by new residents. These people changed the plan of the compound and adapted it for their needs.

Dr. Yuval Baruch, the Jerusalem Regional Archaeologist of the Israel Antiquities Authority, notes that “after exposing the compound and recognizing its importance, the Israel Antiquities Authority and Ministry of Construction and Housing undertook the measures necessary for preserving and developing the site as an archaeological landmark in the heart of the new neighborhood slated to be built there”.