On the day of the Triumph of Orthodoxy we celebrate the Church’s victory over all the heresies in its history, the close of an epoch of great Christological debates. But the event that served as the cause for the establishment of this celebration is the triumph over iconoclasm.

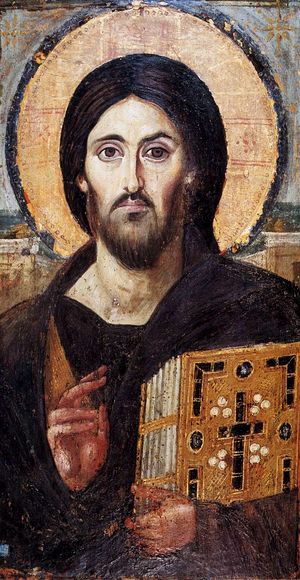

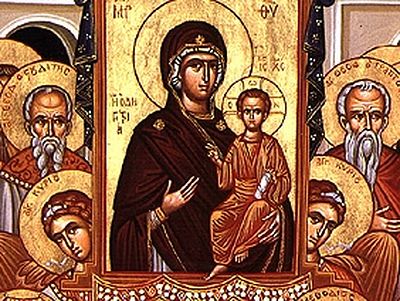

The Church successfully defended the veneration of holy icons. We today enter under the vaults of a church and we are met by the face of the Lord and of the saints, and scenes from the story of our salvation, because at that time the Seven Ecumenical Council established that, “Befitting the shape of the precious and vivifying Cross, that the venerable and holy icons, painted or mosaic, or made of any other suitable material, be placed in the holy churches of God upon sacred vessels and vestments, walls and panels, houses and streets, both of our Lord and God and Savior Jesus Christ, and of our Pure Lady the holy Theotokos, and also of the precious Angels, and of all Saints.”

The religious educational, theological meaning of this triumph is very great, but much has already been said about this. I would like to take a look at what went on from a slightly different angle—from the angle of the interrelationship between faith and culture.

Iconoclasm, besides everything else, meant a divorce between faith and art. This can be seen very well in the example of a more recent wave of iconoclasm closer in time to us—the Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century. I once watched a documentary serial on the BBC about the history of English art. The small number of images from medieval ecclesiastical art preserved to our time in England produce an astounding impression of heavenly beauty; but alas, there are very few. Judging from these images, England might have occupied a place in the art world on a level with Italy or even surpassed it, but this great and flourishing culture was destroyed almost entirely. One can evaluate the spiritual fruits of the Reformation in various ways, but regarding the cultural sense it was a catastrophe. The zealous puritans, brimming with the resolve to uproot everything that departed from their reading of the Word of God, burned icons, scraped away frescoes, smashed mosaics, and left the ancient churches empty. And when they built new ones they were overly simple houses, where neither architecture, nor especially images might distract the congregation from the only thing that deserved attention in the Puritans’ eyes—the Bible. Nowadays there are often parallels drawn between them and the Wahabbis [Islamic extremists], and though all analogy proves a little lame, vandalism under the flag of a “war on idol worship”, so familiar to us from recent news, was waged with great force in those times as well.

Only a one hundred years later, in the nineteenth century, when the furious enmity with Rome began to cool down, in the era of neo-gothic renaissance the English began once again to build churches that would be a least somewhat more worthy of that country’s former glory—churches that they were now afraid to adorn with images of the Lord Jesus, angels, and saints.

The same Reformation in Holland did not kill visual arts, but it did almost entirely push it out of religious spheres. An artist might have been pious, but he no longer served God with his art—he only earned a living. People no longer adorned churches but drew portraits, still lifes, or domestic scenes, as the soviet-era textbooks wrote of them approvingly: “They returned to real life.”

And all of this beauty that fell under the Puritans’ axes—was it the glorification of God (as the medieval artists saw it), or pagan defilement (as the Puritans saw it)?

Does the Incarnation mean that this is also facet of our nature—the ability to create and comprehend beauty, redeemed by Christ, and has its place in His Kingdom? Can an artist enter a church and place his gifts at the feet of Christ, or should he leave them at the door?

Is beauty—the beauty of God’s world and the beauty created by pious people—a witness to God, or is it something unnecessary and empty? Holy Scripture points to the former. We read how the psalmist glorifies God for His creation: Confession and majesty are His work; His righteousness abideth unto ages of ages (Ps. 110:3). We learn how God endows builders with special gifts to adorn His tabernacles: And the Lord spake unto Moses, saying, See, I have called by name Bezaleel the son of Uri, the son of Hur, of the tribe of Judah: And I have filled him with the spirit of God, in wisdom, and in understanding, and in knowledge, and in all manner of workmanship, to devise cunning works, to work in gold, and in silver, and in brass, and in cutting of stones, to set them, and in carving of timber, to work in all manner of workmanship. And I, behold, I have given with him Aholiab, the son of Ahisamach, of the tribe of Dan: and in the hearts of all that are wise hearted I have put wisdom, that they may make all that I have commanded thee; The tabernacle of the congregation, and the ark of the testimony, and the mercy seat that is thereupon, and all the furniture of the tabernacle (Ex. 31:1-7).

God loves beauty; He created it; He endows us with the ability to appreciate beauty, and some of us with the ability to create it. Sometimes we are asked why we so bountifully adorn our churches. After all, God hears us even if we pray in a barn… The answer is obvious: Because God created us as beings capable of appreciating and loving beauty, and if we strive to live amidst beauty and not ugliness, then shouldn’t we before all adorn the place where we worship God?

And if beauty is redeemed by Christ, then first of all in order to witness to the beauty of His Kingdom and instruct people in faith and piety. As the fathers of the Seventh Ecumenical Council said, “For the more frequently and oftener they are continually seen in pictorial representation, the more those beholding are reminded and led to visualize anew the memory of the originals which they represent and for whom moreover they also beget a yearning in the soul of the persons beholding the icons. Accordingly, such persons are prompted not only to kiss these and to pay them honorary adoration, what is more important, they are imbued with the true faith which is reflected in our worship which is due to God alone and which befits only the divine nature. But this worship must be paid in the way suggested by the form of the precious and vivifying Cross, and the holy Gospels, and the rest of sacred institutions, and the offering of wafts of incense, and the display of beams of light, to be done for the purpose of honoring them, just as it used to be the custom to do among the ancients by way of manifesting piety. For any honor paid to the icon (or picture) redounds upon the original, and whoever bows down in adoration before the icon, is at the same time bowing down in adoration to the substance (or hypostasis) of the one therein painted.”