Source: Truth and Charity Forum

By Mitchell Kalpakgian, Ph.D.

In C. S. Lewis’s That Hideous Strength Mark Studdock undergoes an indoctrination into the perverse called “a systematic training in objectivity” that is compared to “killing a nerve”. As Frost, one of the influential members of the intelligentsia, explains, the acquisition of the higher knowledge of the elite demands that the novices acquire a new sensibility: “That whole system of instinctive preferences, whatever ethical, aesthetic, or logical disguise they wear, is to be simply destroyed.” Frost leads Studdock into a room designed for a committee meeting, a stark place with no windows and no fireplace. Abnormally high and claustrophobically narrow, the room is deliberately “ill-proportioned”, just slightly skewed so as not to be strange. Studdock then notices a door that also appears slightly odd but not too distorted: “The point of the arch was not in the center: the whole thing was lop-sided.” Then, Studdock observes a number of random black spots on the ceiling that “hover on the verge of regularity”, suggesting some design or order “and then frustrating the expectation thus aroused.”

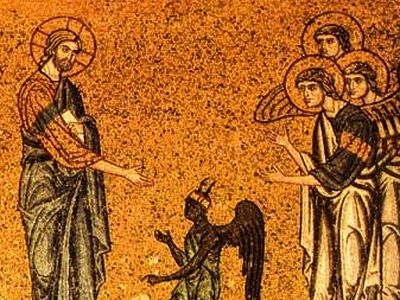

The pictures in the room also violate the sense of the natural. One depicts a woman with her mouth open showing a growth of hair in the cavity, another an image of a man with corkscrews for arms, and another with beetles under the table during the Last Supper. “Every fold of drapery, every piece of architecture, had a meaning one could not grasp but which withered the mind.” In other words, Studdock’s training in “objectivity” in the strange room initiates his dehumanization—“the process whereby all specifically human reactions were killed in a man so that he might become fit for the fastidious society of the Macrobes” (the atheistic social engineers who make man god). Lewis shows that the obsession with the perverse inevitably leads to diabolical evil. Once the idea of the natural and the sense of the normal are subverted, the moral sense also becomes desensitized, and the unnatural and the abnormal become customary. Evil becomes good. In That Hideous Strength, the perverse instinct supplants the rational with the irrational and oversteps all norms and logical distinctions in its willful attempt to reinvent the structure of reality and to recreate human nature according to some scientific model “cut off from Earth their mother and from the Father in Heaven.”

Mark Studdock, fascinated and flattered by the progressive coterie who are indoctrinating him with the modern sensibility that desensitizes him to the human, natural, and the moral, suddenly discovers the nature of the perverse when isolated in the “long, high coffin of a room” with the strange sights and weird paintings. Instead of undergoing an education in so called “objectivity,” the experience has a different result: “the built and painted perversity of this room had the effect of making him aware, as he had never been aware before, of the room’s opposite . . . .Something else—something he vaguely called the “Normal’—apparently existed.” Lewis explains that just as the desert evokes the living reality of the goodness of water and just as the absence of the beloved moves the heart with a great longing, “there rose up against this background of the sour and the crooked some kind of vision of the sweet and the straight.”

The reality of The Normal that Studdock associates with his wife Jane, fried eggs, birds, the sea, and sunlight exposes the Perverse for the inhuman, unnatural, irrational, sordid thing it is. For Studdock, this discovery of the standard of the Normal heightens his moral awareness to a degree unknown before. He feels embattled, impassioned by conviction, and inspired by courage: “He was choosing a side: the Normal,” and he abandons himself to all the consequences that follow from moral certainty. If modern scientific theory does not acknowledge the criterion of the Normal, “then be damned to the scientific point of view!” If Studdock’s rejection of the dehumanizing doctrines of the modern scientific sensibility provokes the wrath of its leaders, “he hardly cared if Frost and Withers killed him.”

Despite the modern heresy that views the criterion of the Normal as superstition, the rational, the natural, the human, and the normal all reflect aspects of the moral. The good is reasonable, “knowing what to do with things” according to their intended design and purpose as Robert Frost writes in his poem “At Woodward’s Gardens”—not using a glass mirror to concentrate light to burn a monkey’s nose in the zoo. The good is naturallike birds, flowers, and children—“something you could touch, or eat, or fall in love with,” Lewis writes: “It was mixed up with Jane, and fried eggs and soap and sunlight and the rooks cawing at Cure Hardy and the thought that somewhere outside, daylight was going on at that moment.” The good is human: it respects human life, loves one’s neighbor, and practices charity and justice to all persons—the opposite of the sins of fraud, violence, and treachery condemned in the Inferno that result in injury to neighbor (arson), to self (suicide), or to God (blasphemy). And the good is normal, located in marriage, children, the home—all the primary realities that Mark Studdock compromised in his aspirations to join the inner circles of the illuminati fantasizing about their new world order of population control and technocracy. Once the notion of the Normal captures the mind, then the beauty of goodness and the ugliness of evil establish themselves as universal truths, and the perverse is recognized for its diabolical nature, a product of hell. The discovery of the Normal is liberating and enthralling, the road to human happiness as Mark Studdock discovers: “And day by day, as the process went on, that idea of the Straight or the Normal which had occurred to him during his first visit to this room, grew stronger and more solid in his mind till it had become a kind of mountain.” The recovery of the Normal and the recognition of the Perverse (“the Immoral Sense”) lead to moral sanity.

Modernity assumes that psychological techniques, propaganda, brainwashing, indoctrination, and ideology can condition human nature to lose the sense of the Normal in a way that resembles Mark Studdock’s situation in the narrow room with the high ceiling. Only the deformed sensibility of Men without Chests can ignore the ugliness of killing children in the womb, the perversity of same-sex unions, the selfishness of marital acts reduced to contraceptive habits, the shamefulness of cohabitation, and the untold suffering of families that undergo divorce. These are not subjective responses or religious opinions but moral sentiments rooted in the objective nature of things that the human race calls Normal.