Source: Huffington Post

Professor of English at University of MIssouri and Founding Director of MU Writing Workshops in Greece, and noted Orthodox poet, Scott Cairns writes in a new Huffington Post blog posting:

* * *

I'm very pleased to report that in March of 2017, Paraclete Press will release the second, expanded edition of my spiritual memoir, Short Trip to the Edge, originally published in 2007 by HarperOne. This coming December, I will be making my twenty-first such pilgrimage. Until the book reappears, I hope to share some of the text with readers of the blog here on Huffington Post.

Preamble

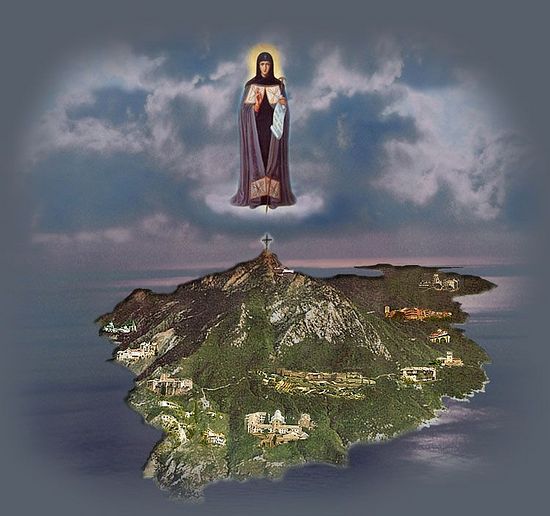

In spring of 2007, I first published Short Trip to the Edge, an account of my first three pilgrimages to Agion Oros, the Holy Mountain--a monastic peninsula in northern Greece that is perhaps more widely known in as Mount Athos. It is, to be sure, a uniquely holy place, one of those places our Celtic saints would have characterized as a thin place. I understand their sense of such places as physical spaces in which the veil between heaven and earth seems transparent or porous, sites whose substance thins to yield apprehension of an occasion of greater substance; in my thinking, a more likely characterization of such scenes would be that they themselves have attained a palpable presence of the invisible enormity in which we live and move and have our being; that is, the places themselves register as thick, full, densely inhabited by holy presence.

Since those first three visits in 2004 and 2005, I have, at this writing, made an additional seventeen pilgrimages. Much has happened in the interim, and much more is afoot. Therefore, I had hoped for this edition to expand the epilogue of the original text in order to bring the reader a sense of an ongoing synergy, the collaboration between heaven and earth--which is what the Holy Mountain represents, and what the Holy Mountain performs. As it happens, the much more that is afoot is not quite ready for prime time; that is to say, we must be patient--which, among many other lessons from the fathers, is something I'm better at now than I was when I set out.

In the meantime, I have sought to correct what many have identified as an oversight; this edition includes both maps and photographs. This edition also does what I should have done from the first; with two exceptions--those of Father Iákovos and Father Matthew--I have changed the names of my beloved fathers in hopes of mitigating any undue attention to them, attention which might make more difficult the lives of prayer to which they are, by God's grace, committed.

Please accept this new edition as one that corrects certain errors of an enthusiastic pilgrim, and one that further extends the narrative to account for another several years along the way. Good journey, as the Greeks like to say--Καλό ταξίδι! Good road--Καλό δρόμο!

May your way be blessed.

Chapter 1.

Lord, I believe. Help my unbelief.

The boat is the Axion Estin, and I am finally on the boat.

The concrete pier at the bow marks the end of the world, where lies a modest village with an ambitious name; it is Ouranoupoli, Heaven's City. We remain bound to its bustling pier by two lengths of rope as thick as my thigh.

Any moment now, the boat will be loosed and let go, and we will be on our way to Agion Oros, the Holy Mountain.

The air is sun-drenched, salt-scented, cool, and pulsing with a riot of gulls and terns dipping to grab bits of bread laid upon the water for them. The Aegean reflects the promising blue of a robin's egg. A light breeze dapples the surface, reflecting to some degree the tremor I'm feeling just now in my throat.

I've been planning this trip for most of a year.

I've been on this journey for most of my life.

For a good while now, the ache of my own poor progress along that journey has been escalating. It has reached the condition of a dull throb, just beneath the heart.

By which I mean, more or less, that when I had traveled half of our life's way, I found myself stopped short, as within a dim forest.

Or, how's this: as I walked through that wilderness, I came upon a certain place, and laid me down to sleep: as I slept, I dreamed, and saw a man clothed with rags, standing with his face turned away from his own house, a book in his hand, and a great burden upon his back. He opened the book, and read therein; and, as he read, he wept and shook, and cried out, saying, What shall I do?

Here's the rub: by the mercy of God I am a Christian; by my deeds, a great sinner.

You might recognize some of that language. You might even recognize the sentiment. These lines roughly paraphrase the opening words of three fairly famous pilgrims, the speakers of Dante's Divine Comedy, Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress, and the Russian devotional favorite known as The Way of a Pilgrim.

In each of them I find a trace of what Saint Paul writes to the church in Rome in the first century: I do not understand what it is I do. For what I want to do, I do not do; but what I hate, I do.

I get it. I really do get it.

In each of these confessions I suspect a common inference as well: something is amiss. There is a yawning gap between where I am and where I mean to go.

Lately, the crux of my matter has come pretty much down to this: having said prayers since childhood, I startled one day to the realization that--at the middling age of forty--I had not yet learned to pray.

At any rate, despite half a lifetime of mostly good intentions, I had not established anything that could rightly be called a prayer life.

I remember the moment of this realization with startling clarity, and with a good dose of chagrin. I was romping at the beach with Mona, our yellow Labrador. It was a gorgeous morning in early spring--absolutely clear, the air still crisp, tasting of salt from the bay, the water and sky mirroring a mutual, luminous turquoise.

I was throwing a stick of driftwood, repeatedly--as instructed in no uncertain terms by my ecstatic dog--into the Chesapeake for her to retrieve, and I was delighting in the sheer beauty of her astonishing leaps into the surf--wholehearted, jubilant, tireless--, followed by her equally tireless insistence that I keep it up. She yelped, she pranced, she spun like a dervish as water poured from her thick coat into the flat sheen of sand at the water's edge.

In short, I was in a pretty good mood.

I was sporting cut-off jeans in February. I was barefoot. I was romping with my dog at the beach.

I was not the least bit depressed, nor even especially thoughtful. I had hardly a thought in my head at all.

I was, even so, feeling a good deal--feeling, actually, pretty pleased with myself, and feeling especially pleased with that radiant morning on the shore, accompanied by a deliriously happy dog. My best guess is that, after some years of high anxiety, I was finally relaxed enough to suspect the trouble I was in.

We had moved to Virginia Beach about a year earlier, having arrived there with a palpable sense of reprieve from a stint of--as I have come to speak of it--having done time in Texas. I had left a difficult and pretty much thankless teaching job in north Texas in favor of a similar but far more satisfying gig at Old Dominion University in Norfolk. We'd extricated our little family--by which I mean me, Marcia, our ten-year-old Liz, and our five-year-old Ben--from our run-down cottage in a run-down corner of a small (and, at the time, relatively run-down) north Texas town; we'd swapped those derelict digs for a bright, airy bungalow by the beach.

The contrast was stunning. Our first evening there, in

fact, sitting at an oceanfront café, we were

treated to the spectacle of a dozen or more dolphins

frolicking northward as they proceeded to the mouth of the

Chesapeake half a mile up.

Life looked good. It looked very good. It even tasted

good.

I felt as if I had found my body again after having misplaced it for four intermittently numbing years in exile. I had even started running again, running on the Chesapeake beach or along the state park bike-path most mornings before heading off to my job in Norfolk.

In the midst of such bounty and such promise, and provoked by nothing I could name, I suddenly thought what might seem like a strange thought under the circumstances. At the age of forty, I had accomplished only this: I saw how far I had gotten off track.

It was as if those difficult years in Texas had somehow distracted me from seeing that the real work--the interior work--was being neglected. And, to be honest, my difficulty with a handful of colleagues there and a regrettable lack of humility on my part had led me to speak and act in ways I knew, even at the time, to be wrong, ways that ate at me still.

Shame is a curious phenomenon. It can provoke further, entrenched, and shameful response--compounding the shame, compounding the poor response, ad infinitum--or like a sharp and stinging wind it can startle even the dullest of us into repentance. Now that my job was once again rewarding, now that my family was safe and happy, I relaxed enough to glimpse a subtle reality: I saw how far I stood from where I'd meant to be by now.

Rather, I saw how far I stood from where I'd meant to be by then.

I have recently turned fifty. And though it is possible that some progress has been made in the intervening ten years of meantime, that progress has been very slow, negligible, and remarkably unsteady, with virtually every advance being followed, hard on the heels, by an eclipsing retreat--with hard words, harsh thoughts continuing to undermine any accomplishment in the realms of charity and compassion.

In his Christmas oratorio, For the Time Being, the beloved Mr. Auden puts it in a way that never fails to resonate with me, to slap me awake when I recite his poem (which I do as a matter of course every Christmas Eve): "To those who have seen / The Child, however dimly, however incredulously, / The Time Being is, in a sense, the most trying time of all."

I get that, too.

Wise men and women of various traditions have troubled the terms, being and becoming, for centuries without arriving at anything like conclusion. Every so often, though, I glimpse that some of the trouble may derive from our merely being, when--as I learned to say in Texas--we might could be becoming.

I wonder if we aren't fashioned to be always becoming, and I wonder if the dry taste in my mouth isn't a clue--and even a nudge--that staying put is, in some sense, an aberration, even if it may also be a commonplace.

I have been a Christian virtually all of my life, have hoped, all of my life, to eventually find my way to some measure of . . . what? Spirituality? Maturity? Wisdom? I'd hoped, at least, to find my way to a sense of equanimity, or peace, or...something.

As one desert father, Abba Xanthias, observed--clearly anticipating my Labrador--"A dog is better than I am, for he has love and he does not judge."

At the age of forty, I raised my arm to fling a sodden stick into the Chesapeake; I looked down to see my beautiful, dripping yellow dog--braced, alert, eager, her eyes lit up with wild expectation. I didn't want to let her down.

My life at that precise moment reminds me of the bumper sticker I saw years ago: "I want to be the man that my dog thinks I am."

More generally, my life at that moment reminds me of an often repeated comment one monk made to a visitor to Mount Athos. I imagine it like this: The visitor asks what it is that the monks do there; and the monk, looking up from the black wool of the prayer rope he is tying, stares off into the distance for a moment, silent, as if wrestling with the answer. Then he meets the other man's eyes very directly and says: "We fall down, and we get up again."

A little glib, but I think I get the point.

Monks, it turns out, can seem a little glib on occasion, and, I've noticed that they have a general penchant for the oblique; but I'll have more to say about that by and by.

As for me, at the moment when my brilliant day at the beach was suddenly clouded by an encroaching unease, I saw that I was less like that diligent monk, and more like the actor in the TV ad who says I've fallen, and I can't get up.

Even if the monk's words do offer a glimpse of a truth that is available to us all, I keep thinking that--for the saints, for the monks, for the genuinely wise, presumably for anyone but me--the subsequent fall needn't seem so completely to erase all previous progress.

I keep thinking that, for the pilgrim hoping to make any progress at all, the falling down must eventually become less, that the rising up must become something more--more of a steady ascent, and more lasting.

I also have an increasing sense that the subsequent fall

need not be inevitable.

I keep thinking that this is actually possible--the

proposition of spiritual development that leads us into

becoming, and--as the fathers and mothers of the Eastern

Christian tradition would have it--into always becoming.

The question must be how to get from here to there.

And that question has pressed me to get serious, to slap myself awake, take up my bed and get to walking.

I hope to be, at long last, a pilgrim on the way.