Source: Russia, Eurasia, Meta- and Geopolitics, Culture

April 22, 2015

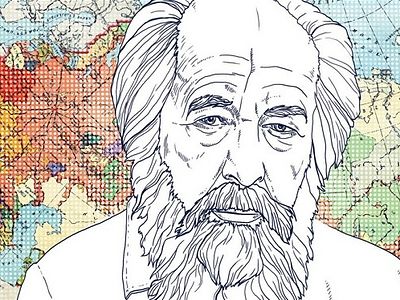

Alexander Solzhenitsyn is one of the best-known Soviet dissidents, so much so that he earned the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1970. His Gulag Archipelago, written in the 1950s-60s, and One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich from 1962—both about the Stalin-era labor-camp system—are his most famous works outside of Russia. Yet after the collapse of the USSR, it became increasingly clear that much of his foreign support was not inspired by the Western ideal of ‘human rights’ or concern for average Russians, but served as a tool of geopolitics instead.

His statements about resurgent Russia, particularly in the last years before his death in 2008–well into the era of Putin’s leadership–did not suit those that would rather have the country in the permanently weak state of ‘freedom’ and ‘democracy’ of the 1990s, so that its resources could continue being plundered by domestic oligarchs and foreigners alike, while its culture–transformed into the soft authoritarianism of neo-Liberal Postmodernity. In contrast, one of the most attractive aspects of Putin’s Russia for Solzhenitsyn was the revival that Orthodox Christianity continues to experience.

In the eyes of Western mainstream opinion-makers—that is, in the Anglosphere, specifically—at best, Solzhenitsyn’s support for Putin made him a “puzzle.” At worst, his patriotism, referred to as “nationalism” with a derogatory connotation, is said to be “off-putting,” “bizarre,” and an “irony.” Newsweek even presented a ‘psychological evaluation’ of Solzhenitsyn, concluding that he suffers from the “Gulag of the Russian mind.” Indeed, it has become increasingly difficult to use his scathing criticism of certain Soviet policies in light of his advocacy for Russia’s own organic path that includes a set of geopolitical interests. The latter was dubbed as anti-Western.

The final straw seems to have arrived following Ukraine’s coup d’état in 2014 that was backed by Washington and Brussels, when several Russian-language publications decided to revisit Solzhenitsyn’s statements about the two neighboring countries made throughout his life. A number of his comments has been translated into English, and are well worth examining. Solzhenitsyn felt greatly attached to this subject because “Ukraine and Russia are merged in my blood,” he wrote. I provide another translation of excerpts from a book called Russia in Collapse (Rossiia v obvale, 1998) below. Unsurprisingly, Western officialdom found his goal of returning to a historic union of Russia and Ukraine highly problematic. Others simply criticized his statements for being uninformed, suggesting that writers should stay away from international relations.

But the “irony” that the mainstream opinion-makers in the West described was actually on them: Solzhenitsyn was, in fact, consistent in his critique of the Soviet nationalities policies that, at times, divided regions administratively, without accounting for their ethno-cultural makeup. This was the case with Crimea and Donbass, the tragic results of which have become too obvious in the past year.

Falling out of favor with Cold Warriors and their heirs alike, one might reconsider the Archipelago itself. While this massive text undoubtedly has both literary and historic value, it cannot be used for statistical analysis by definition. After all, it was, in part, based on eyewitness testimony and available Soviet legal decrees, rather than those documents that only became declassified after 1991. Neither can this text be employed to describe the entire Soviet era or, for that matter, contemporary Russia, the way propagandists do with their persistent Putin-Stalin trope. Looking to understand that turbulent period, paradoxically both tragic (from collectivization to the purges) and triumphant (from industrial feats and increased literacy to the elimination of childhood mortality and epidemic diseases, to say nothing of the Great Patriotic War), one is best to go directly to factual archival data compiled by historians rather than falling for the deliberately exaggerated claims by those who seek to use this author to undermine Russia.

The following excerpts from “Slavic Tragedy” (Slavianskaia tragediia), a chapter in Russia in Collapse, will demonstrate why some journalists in his homeland referred to Solzhenitsyn’s words—from his comments about the Church to the question of language—as “prophetic.” And why the West’s favorite Soviet-era dissident has become so geopolitically inconvenient as of late will also become clear.

ON CRIMEA

In terms of autonomous development—may God grant Ukraine every success in this endeavor. Its grave mistake lies specifically in its excessive expansion into those lands that were never Ukrainian prior to Lenin: two Donetsk regions, the entire southern strip of Novorossia (Melitopol-Kherson-Odessa), and Crimea.

(Accepting Khrushchev’s gift was, in the very least, done in bad faith, including the appropriation of Sevastopol, despite—I’m not saying “Russian sacrifices”—but also from the standpoint of Soviet legal documents, this was state theft)…

How many Russians—with indignation and horror—lived through the 24-hour hand-over of Crimea, lacking any will and uncontested in any shape or form thanks to the nature of our sagging diplomacy back then? Then came its betrayal in every Crimean conflict. And the obedient hand-over of Sevastopol—the diamond of Russian military valor—without even the smallest political steps. This evil was committed by our elected government; however, we, citizens, did not oppose it in time either. And now for the long foreseeable future, the upcoming generations will have to accept this…

Pushing out the Black Sea Fleet from Sevastopol is the lowest, evil abuse of the entire Russian history of the 19th and 20th centuries. Under all these conditions, Russia cannot dare indifferently betray those millions of Russians in Ukraine in any shape or form, or renounce our unity with them.

ON THE RUSSIAN LANGUAGE

The Ukrainian authorities had chosen the path of forcefully persecuting the Russian language. Not only did they deny its right to become the second state language, but they are also zealously pushing it out of radio, television, and print media. Everything is done in the Ukrainian language in post-secondary institutions, from the entrance exam to the final project, and it is too bad if the terminology is insufficient. School programs either completely exclude Russian, or introduce it as a “foreign” language in an elective course; they completely pushed out the history of the Russian state and almost all the Russian classics from the literature courses. We hear accusations along the lines of “Russian linguistic aggression” and “Russified Ukrainians are the fifth column.” Thus begins the suppression of Russian culture, rather than the growth of the Ukrainian one. And they persist in oppressing the Ukrainian Orthodox Church—the one that remained loyal to the Moscow Patriarchate with its 70% of Ukrainian Orthodox…

One of the many churches destroyed during the 2014-15 war in Donbass. Source: Donetsk, Mikhail Sokolov, TASS.

One of the many churches destroyed during the 2014-15 war in Donbass. Source: Donetsk, Mikhail Sokolov, TASS.

The fanatical suppression and persecution of the Russian language (which the previous polls demonstrated as the main language for more than 60% of the population) is a brute measure, one that is directed against the cultural prospects of Ukraine itself.

ON THE UKRAINIAN LANGUAGE

In rejected Galicia, accompanied by Austrian mocking, there grew a distorted Ukrainian language that was not of organic nature [non-Volk, nenarodnyi-Ed.], packed with German and Polish words …

Even the ethnic Ukrainian population does not speak or use the Ukrainian language under many circumstances. Thus, there must be measures of transferring all nominal Ukrainians into the Ukrainian language. Then, there will obviously be the task of making Russians use the Ukrainian language, too (and this already—not without violence?). Then, the Ukrainian language is yet to vertically sprout into the upper strata of science, technology, and culture—this task is ahead, too. Furthermore, the Ukrainian language must become mandatory in international relations. Perhaps, all these cultural tasks might need more than a single century. For now, we are reading the news about the persecution of Russian-language schools, even thuggish attacks on Russian schools, about ceasing to broadcast Russian television in certain places all the way through to the ban on the Russian-language use between librarians and readers. Is this really the development course of Ukrainian culture?

ON THE PLANS OF THE WEST

Ukraine’s anti-Russian position is precisely what the United States needs. Ukrainian government subserviently plays along with the American goal of weakening Russia. And this [strategy] quickly reached the “special relationship of Ukraine with NATO” and the US navy exercises in the Black Sea. One is forced to recall Alexander Parvus’s [Marxist revolutionary—Ed.] immortal plan of 1915: using Ukrainian separatism to succeed in breaking up Russia.