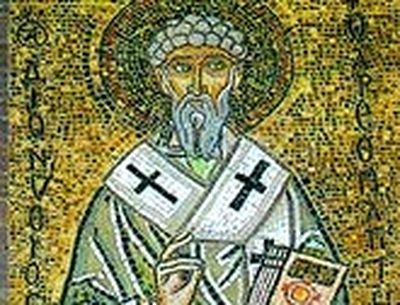

Today the Church celebrates the memory of St. Dionysios the Areopagite, one of the few Athenians who responded to the apostle Paul’s speech on the Areopagus, and became a Christian.

A remarkable pilgrimage book by H. V. Morton, In the Steps of St. Paul (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1936) takes us to the Areopagus in Athens in the early twentieth century, with notes on this place so famous to Christian history (pp 312-322).

* * *

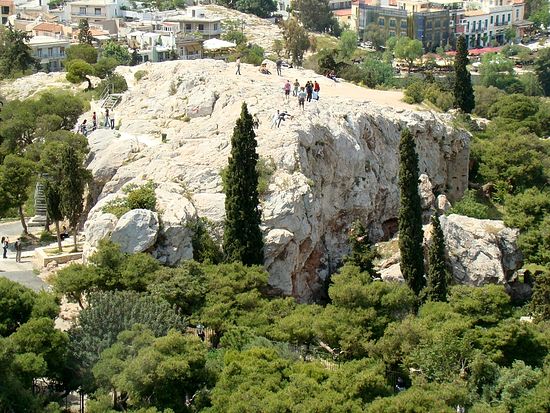

Descending from the Acropolis, I saw on the right a high outcrop of rock. It is separated from the Acropolis by a narrow path, and an ancient staircase of about fifteen or sixteen steps leads to the top, where the rock bears trace of having been artificially levelled. This is the Areopagus, the ancient meeting-place of the famous assembly before whom St. Paul delivered his speech to the Athenians.

Some people believe that the rock of the Areopagus is the spot from which the Apostle spoke, while others consider it more probable that he addressed the assembly from some other place, possibly the agora or the King’s Stoa. If the first are correct, St. Paul must have ascended these rock-cut steps, he must have stood on this commanding crag, and, as he told his listeners that God “dwelleth not in temples made with hands,” he must have pointed towards the Acropolis, rising a few paces from him, crowded with marble temples and dominated by the colossal Athena whose gold spear-tip was visible to mariners at Sunium.

During the summer the Areopagus is one of the loneliest places in Athens. Few people care to visit that unshaded rock. It is haunted only by a melancholy man in a black hat, who sidles up to the visitor and says: “Mister, I will show you where St. Paul made his speech.” Finding it less irritating in the long run to indulge guides who, having good memories, ever after leave one in peace, I allowed him to lead me to a certain portion of the flat rock, where he delivered his stilted little speech in a pathetic atmosphere of anti-climax. From that time onwards, when I went there early in the morning or in the cool of the evening, he would rise and touch his black hat to me; and we became quite friendly. On one occasion he introduced his little boy to me, a lad who, from the look of him now, will grow up to be a terror to tourists in twenty years time. So in this easy way I purchased the freedom of the Areopagus. I rarely met a soul when I went there to sit and watch the Propylaea change colour in the setting sun. When St. Paul came to Athens, the city had fallen from its ancient splendour. The great days of Hellas were as distant from the Apostle as the Tudor Age is from ourselves. Marathon and Thermopylae were as remote to him as Bosworth Field is to a modern Englishman. I have no idea whether St. Paul had ever read Homer, Thucydides or Herodotus, or whether he took any interest in the history of the race whose language he spoke; but surely, as a liberal-minded Hellenist and the child of a great Hellenistic university town, he must have felt his pulse quicken when he approached Athens.

As he walked beside the Long Walls and saw the Acropolis rising from the plain, the Voice of Jesus may have sounded in his ears, in words like those recorded by St. John: “And other sheep I have, which are not of this fold: them also I must bring, and they shall hear my voice; and there shall be one flock and one shepherd.”

In preaching the Gospel in Athens, for the first time in his life, the Apostle stood alone in a world-renowned city of the West. It is true that he had turned to the Gentiles at Pisidian Antioch, but he had approached them through the synagogue. He had journeyed among the Jews of the Dispersion through Asia Minor and Macedonia; but in Athens that world was behind him and he stood alone, the first Christian missionary in the intellectual stronghold of the Roman world. I think there are few moments in the history of early Christianity more dramatic, or in their sequel more notable, than the moment when the eyes of St. Paul first saw the Acropolis.

Athens at that time was not even the capital of the Roman senatorial province of Achaia. The Pineus had silted up, and the commercial life of Greece had moved to the new Roman colonies of Patras, Nicopolis, and, above all, to the capital of the province, Corinth, a city almost as rich and dissolute as Syrian Antioch. But Athens, although no longer powerful commercially or politically, was still the most famous city in Greece. She survived by virtue of her past glory. The Romans were the first Philhellenes, and in their sometimes contemptuous affection they pardoned Athens deeds that would have brought destruction on any other city in the Empire. In the afterglow of creation, the once-splendid city of Pericles and Plato was content to be the university of the Roman world. She gave herself all the airs of greatness, but she no longer created anything: she merely criticized. She no longer did anything: she read history instead. Her academies and her streets were filled with the arguments of Platonists, Peripatetics, Stoics and Epicureans.

At this period the moral and intellectual decline of Athens appeared complete. From Theomnestus, Curator of the Academy in 44 B.C., to the time of Plutarch’s teacher, Ammonius Alexandreus, who taught in the last decade of the first century, no man of first-rate importance was produced by Athens. It is only fair to remember, of course, that intellectual Centres had developed at Rome, Alexandria, Antioch, and Tarsus, and perhaps a share of the intellect, that would in ancient times have blossomed in the shadow of the Acropolis, was at this period spread about the world.

Outwardly Athens was, perhaps, more brilliant than ever. Her streets were thronged with the rich youth of the world. Philosophers and teachers were never more numerous. Distinguished men banished from other lands could always find a happy retreat in a city that, in spite of its mental and moral decline, was still a great intellectual force. Tourists on their way to visit the ruined temples of Egypt, and to write their names on the base of the Colossi at Thebes, would break their voyage at Athens. These first Hellenic travellers, led by their voluble guides, would visit the famous relics of the past, inspecting the statues and the works of art, standing in awe on the Acropolis, where the temples, blazing with gold and colour, stood among their crowded votive-offerings much as they did in the time of Pericles. Athena Promachos rose above them, grasping her golden spear.

Although Athens had begun to decline, she preserved her antiquities and monuments, for on them her existence depended. She multiplied the number of her festivals. The sacrifices offered at her temples, and the succession of great occasions which attracted pilgrims from every part of the world, never failed to astonish those who visited the city. In addition to the Dionysia, the Panathenia, and the annual mysteries at Eleusis, historical events, such as the Battle of Marathon and the birthdays of men like Plato and Socrates, were religiously commemorated, giving to the present a vivid beauty and excitement. At the time of St. Paul’s visit to Athens, another wayfarer, in whom many a modern reader must have detected a first century Bernard Shaw, was making the same journey. This was Apollonius of Tyana, whose encounter with the customs official I have already quoted. Like St. Paul, Apollonius noted the fact that at Athens “altars are set up in honour even of unknown gods,” and the sights that met this philosopher, as he walked to Athens from the Piraeus, were the same as those which must have met the eyes of the Apostle. Philostratus, who wrote the life of the sage of Tyana, gives us an intimate glimpse of his journey to Athens.

“Having sailed into the Piraeus at the season of the mysteries, when the Athenians keep the most crowded of Hellenic festivals,” writes Philostratus, “he went post-haste up from the ship into the city; but as he went forward, he fell in with quite a number of students of philosophy on their way down to Phaleron. Some of them were stripped and underwent the heat, for in autumn the sun is hot upon the Athenians; and others were studying books, and some were rehearsing their speeches, and others were disputing. But no one passed him by, for they all guessed that it was Apollonius, and they turned and thronged around him and welcomed him warmly; and ten youths in a body met him and holding up their hands towards the Acropolis they cried: By Athena yonder, we were on the point of going down to the Piraeus there to take ship to Ionia in order to visit you! And he welcomed them and said how much he congratulated them on their study of philosophy. “The experiences of Apollonius in Athens are interesting to the student of Paul’s time because they reflect the scenes in which the Apostle moved. When he reached Athens, one of the first actions of the philosopher was to present himself for initiation into the Eleusinian Mysteries; but he was refused, because, said the hierophant, he had dabbled in magic. Whereupon Apollonius remarked in a blunt and Shauvian manner: “You have not yet mentioned the chief of my offence, which is that, knowing, as I do, more about the initiatory rite than you do yourself, I have nevertheless come for initiation to you, as if you were wiser than I am.”

The degeneracy of the Athens of St. Paul’s time is mirrored in the magnificent denunciation which Apollonius flung at certain dancers at the festival of Dionysius:

“Stop dancing away the reputation of the victors of Salamis, as well as of many other good men departed this life,” was his splendid opening. “For if indeed this were a Lacedaemonian form of dance, I would say ‘Bravo, soldiers; for you are training yourselves for war, and I would join in your dance’; but as it is a soft dance and one of effeminate tendency, what am I to say of your national trophies? . . . You are softer than the women of Xerxes’ day, and you are dressing yourselves up to your own despite, old and young and tender youth alike, you who of old flocked to the temple of Agraulus in order to swear to die in battle on behalf of the fatherland. And now it seems the same people are ready to swear to be come bacchants and don the thyrsus in behalf of their country; and no one bears a helmet, but disguised as female harlequins, to use the phrase of Euripides, they shine in shame alone. Nay more, I hear that you turn yourselves into winds, and wave your skirts and pretend that you are ships bellying their sails aloft. But surely you might have at least some respect for the winds that were your allies and once blew mightily to protect you, instead of turning Boreas who was your patron, and who of all the winds is the most masculine, into a woman; for Boreas would never have become the lover of Oreithya if he had seen her executing, like you, a skirt dance.” While one cannot help feeling that the sage was rubbing it in rather hard, for Athens at this period made no pretense at heroism, one is grateful for this glimpse of the frivolity of a city and the effect it had on an ascetic of the old school. What effect it had on the mind of St. Paul can easily be conjectured. Some writers have imagined the Apostle walking in amazed horror between lines of Athenian statues. I do not believe this. Neither the life nor the religion of Athens could amaze St. Paul. Had he not lived in Syrian Antioch? Graven images were to him an abomination, but he had seen them every day of his life.

I believe that St. Paul joined the crowds of tourists in Athens and visited all the show places with them. He would have entered the Parthenon and looked on the famous Athena of ivory and gold, gleaming in the shaded light, her sandals on the level with a man’s eyes and her helmet-plumes almost touching the roof. He would have seen the Temple of Nike Apteros, the Erechtheum, and the Cave of Pan. I believe that he must have studied, with no pleasure it is true, the great host of statues, Greek and foreign, which stood on pedestals in street and temple.

Now while Paul waited for them at Athens, his spirit was stirred in him, when he saw the city wholly given to idolatry. Therefore disputed he in the synagogue with the Jews, and with the devout persons, and in the market daily with them met with him. Then certain philosophers of the Epicureans, and of the Stoicks, encountered him. And some said, What will this babbler say? other some, He seemeth to be a setter forth of strange gods: because he preached unto them Jesus and the resurrection.

And they took him, and brought him unto Areopagus, saying, May we know what this new doctrine, whereof thou speakest is? For thou bringest certain strange things to our ears: we would know therefore what these things mean. (For althea Athenians and strangers which were there spent their time in nothing else, but to tell, or hear some new tiling.)

How true is this description in Acts of the curiosity and mental restlessness of the Athenians. It is mentioned by Plato, Euthyphron, Phaedo, Protagoras, Demosthenes, and by Plutarch, who commented on the Athenian restlessness, subtlety, love of noise, and novelty. Curiosity mingled with mental arrogance describes the Athenian attitude to St. Paul. The word translated as “babbler” in Acts is spermologos—an Athenian slang term, which means “seed-picker,” and was applied to people who loafed about the agora and the quay-sides, picking up odds and ends. In modern life a spermologos would be a tramp, or one of those who contrive to make a poor living by picking up cigarette-ends and by exploring dust-bins in the morning. As the Athenians applied it to St. Paul, it conveyed contempt. The philosophers believed the Apostle to be a snapper-up of unconsidered theological and philosophical trifles.

Conscious of the contempt with which these arrogant philosophers regarded him, St. Paul nevertheless eagerly agreed to address them. And his address, couched in terms of polite irony, proves that although he may have explored Athens as earnestly as any tourist from Rome or Alexandria, he was unmoved by the sights that impressed other visitors because his mind was wholly occupied with the salvation of Mankind through Jesus Christ. The only things that impressed him in Athens were connected with this mission. Everything else was purely trivial and secondary. So, scorning to flatter the Athenians, as many a philosopher making his first speech must have done, by some graceful reference to the beauty of the city or its ancient fame, St. Paul springs at once to the only thing that impressed him as he wandered the streets of Athens: the multiplicity of altars.

Standing either on the rock of the Areopagus, or among the members of the Court of the Areopagus, he began: Ye men of Athens, in all things I perceive that ye are somewhat superstitious, or as Dr. Moffatt has translated the speech: “Men of Athens, I observe at every turn that you area most religious people. Why, as I passed along, and scanned your objects of worship, I actually came upon an altar with an inscription TO AN UNKNOWN GOD.” It was an excellent beginning. It had the local touch, the right note of something surprising to follow. To everyone who listened to St. Paul, the altars inscribed TO AN UNKNOWNGOD were, of course, a commonplace. Everyone knew the story of the plague that visited Athens in the sixth century before Christ; and how, after sacrifices had been made to every known god and the plague continued, the services of the Cretan prophet, Epimenides, were requested. He drove a flock of black and white sheep to the Areopagus and allowed them to stray from there as they liked, waiting until they rested of their own free will: and on those spots were the sheep sacrificed “to the fitting god.” The plague ceased, and it became the custom, not in Athens alone, to erect altars to unknown deities. St. Paul, having arrested the attention of his audience, then built up his argument:

God that made the world and all things therein, seeing that he is Lord of heaven and earth, dwelleth not in temples made with hands; neither is worshipped with men’s hands, as though he needed anything, seeing he giveth to all life, and breath, and all things; and hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth. . . . St. Paul developed his message with masterly skill and tact. Clever, as always, to suit his words to his audience, he made no mention of the Hebrew scriptures, which would have conveyed nothing to the Greeks, but dealt briefly with fundamental facts of religion.

The Greeks listened carefully to the sermon until the speaker proclaimed the coming Judgment of the World and the Resurrection of Jesus, when they cut him short with the words: “We will hear thee concerning this yet again,” sounded in an atmosphere of contemptuous mockery St. Paul’s address to the Athenians. The apparent failure of his speech, the lofty scorn, the haughty air of amused tolerance with which the Greeks had listened, weighed on the sensitive nature of the Apostle. He was companionless in this strange, vainglorious city; like his Master, he was despised and rejected of men. And into Acts creeps something of Paul’s sadness as he paced the streets of Athens.

Yet history has shown that Christianity has never been more triumphant than in apparent failure. The seeds had been sown. Paul could not know, as he gazed up at the temples on the Acropolis, that the day would come when the mighty Parthenon would be consecrated as a Christian Church dedicated to the Mother of God.

All he saw was that, despite the scorn that had been thrown on him, two human beings had come to him with open hearts, only two from all the thousands in Athens. They were Dionysius, a member of the Areopagus, and a woman named Damaris. Nothing further is known of Damaris, but legend has been busy with the name of Dionysius. According to Eusebius, he became the first Bishop of Athens; but another account says that he went with St. Paul to Rome, stayed with the Apostle until his martyrdom, and then was sent by St. Clement, Bishop of Rome, to preach the Gospel in France. Settling one little island in the Seine, he made many converts and became Bishop of Paris. He suffered martyrdom under Domitian on the Hill of Martyrs (Montmartre), and so became St. Dionysius, or St. Denys, patron saint of France. As I sat one evening on the Areopagus, watching the sunlight fade from the brown slopes of the Acropolis, I thought that Athens contains more buildings that Paul must have seen than any site I had visited in Palestine, Syria, Asia Minor, or Macedonia.

He saw the Acropolis and the buildings whose ruins crown it still: the Propylaea, the Parthenon, the Erechtheum, and the Temple of the Wingless Victory. He saw the Asklepieion, whose ruins are still cut in the side of the Acropolis, and he saw the lovely theatre of Dionysus at the foot of the hill. He saw the Theseum, which today is the most perfectly preserved Greek temple in the world, and he must have seen the Tower of the Winds and the circular Monument of Lysikrates. All these monuments of Paul’s day have defied the chilling touch of time.