Source: Chicago Tribune

November 15, 2016

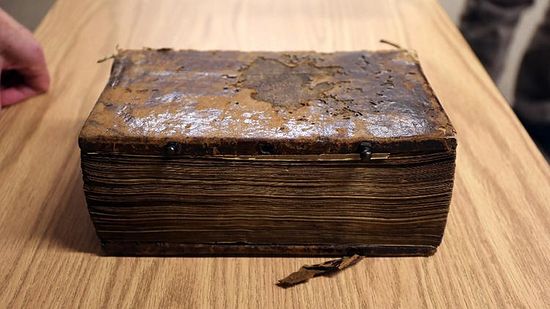

A complete New Testament, handwritten in Greek in the 9th century and looted 99 years ago from a monastery in northern Greece, is being returned by Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago to a Greek Orthodox Church. (Phil Velasquez / Chicago Tribune)

A complete New Testament, handwritten in Greek in the 9th century and looted 99 years ago from a monastery in northern Greece, is being returned by Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago to a Greek Orthodox Church. (Phil Velasquez / Chicago Tribune)

Tuesday morning, the president of a tiny Lutheran seminary on Chicago's South Side is expected to hand a 337-page book to a Greek Orthodox archbishop.

In that simple gesture, the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago, a one-building institution with 225 students, hopes to spark a movement that will lead institutions all over the world to return antiquities to their rightful owners.

That's because the book is a complete New Testament, handwritten in Greek in the 9th century and looted 99 years ago from a monastery in northern Greece. Only 60 of the manuscripts exist. This one is worth at least six figures, far and away the most valuable piece owned by the Lutheran school.

And the seminary is giving it back to the Greek Orthodox Church for free.

"I get that question a lot," LSTC President James Nieman said in his office a few days before the exchange, when asked if his school was receiving compensation.

"No," Nieman said. "It's just a kind of a moral question. It would be weird" to receive money for the book, he added.

Maybe if little LSTC does it, other institutions will follow its lead, Nieman and others said.

"We want to say, even a little school like ours can do something that makes a difference and that is powerful and right," he added, "and we'd like to encourage other institutions who are in a similar circumstance to be able to do the same thing. I think that would be a very important part of this for us."

Eleven hundred years ago, a monk named Sabas copied the manuscript, which other monks added to three centuries later. For hundreds of years, the book was among an estimated 1,300-plus volumes in the library of the Kosintza Monastery near Drama, Greece.

But in 1917 Bulgarian guerrillas, upset over their country's loss in the Second Balkan War, looted monasteries in northern Greece, including Kosintza, and took all the volumes, said New York attorney GeorgeA. Tsougarakis, who represents the church in trying to reacquire the materials.

Those volumes "have been spread all around the globe," Tsougarakis added. In December, the Greek Orthodox Church began sending letters to institutions that possessed the volumes and asked for their return.

The Lutheran seminary is the first institution the church contacted that is returning the materials, Tsougarakis said. "We hope that others will follow the fine example," he said.

Archbishop Demetrios, head of the Greek Orthodox Church in America, traveled from New York to Chicago on Monday to receive the manuscript during a service scheduled for Tuesday morning at the seminary chapel in Hyde Park.

"In the spirit of the upcoming Thanksgiving holiday," Archbishop Demetrios said in a prepared statement, "our hearts are filled with gratitude to our Lutheran brothers and sisters for this generous and kind gesture."

Precisely where the manuscript was kept after its theft remains something of a mystery, although historical records indicate Bulgarian authorities took it to Sofia in 1917. From there, it found its way to Munich, where antiquities dealer Jacques Rosenthal sold it in 1920 to Levi Franklin Gruber, a religious scholar.

Gruber in 1926 became president of Chicago Lutheran Theological Seminary, one of the institutions that later would merge to become LSTC in 1962. He stored it in a bank vault in Chicago and, when he died in 1946, left the manuscript to his wife, who set it up as an annuity, Nieman added.

"The school paid her ... to receive the manuscript into its rare books, along with his other stuff," Nieman said. "It was her retirement plan."

Mrs. Gruber died in 1969.

Through the decades, the school made the manuscript available for serious researchers there and from other institutions, Nieman said. Professors lugged it to class. More recently, the school digitally photographed every page to preserve it in perpetuity.

Tsougarakis sent a letter to LSTC in December asking for the manuscript's return, but the letter was lost in the mail, Nieman said. When the school received a second letter in March, Nieman investigated the possibility of returning it and spoke with the governing board, faculty and others at the school.

"The most surprising thing to me in this process was that not a single person in any of this said we shouldn't do this," Nieman recalled. "They all said, of course we have to do this."

Known as codex 1424, the manuscript's 337 thick, well-preserved pages are made from sheepskin. Its covers are two boards wrapped in leather that worms had damaged "long before it came to the seminary," Nieman said. The school wrapped it in acid-free tissue and a black plastic case and stored it in a third-floor rare collections room, he said.

It is a well-known document in the field of biblical research. About 5,000 Greek New Testaments exist, but many are fragments.

Codex 1424 is known as minuscule, meaning the handwriting is in upper and lower case. Also, the manuscript is the oldest complete New Testament of the Byzantine text family, Nieman said. In addition, it contains prefaces, epigrams, marginal commentaries and other writing that enhance its significance, he said.

"One way of thinking about it is that the current Greek version of the Bible ... derives directly from it," Nieman said. "It's not like Jefferson's original writing of the Declaration of Independence, but it would be like a first edition, printed version of the Declaration that was handed around to real people in Boston."

A week before the service where he would hand over the manuscript to Archbishop Demetrios, Nieman and professor emeritus Ralph Klein, curator of the rare book collection, gave a presentation to let students, faculty and others at the seminary learn about the manuscript and bid it farewell.

All seemed excited at the chance to return the book to its rightful owner, saying that it was a courageous action that builds an ecumenical bridge between Eastern and Western faiths.

"This is an opportunity for us to be selflessly generous," said Paul Eldred, a masters of divinity student, "and when do you get a chance to do that? It doesn't belong here. It belongs in its home."