Source: Notes on Arab Orthodoxy

December 9, 2016

There is no doubt that Saint Luke stresses in his gospel more than the other three evangelists the importance of care for the poor and needy. Where Saint Matthew recounts Christ saying in His Sermon on the Mount, "Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of heaven" (Matthew 5:3), we see Luke transmitting the same words of Christ in the following form: "Blessed are you poor, for yours is the kingdom of God" (Luke 6:20). "The poor in spirit" becomes simply "the poor" without any qualifier.

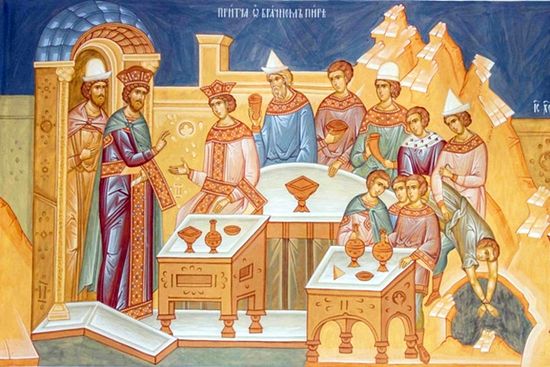

In this context, Christ says to one of the leaders of the Pharisees, "When you give a dinner or a supper, do not ask your friends, your brothers, your relatives, nor rich neighbors, lest they also invite you back, and you be repaid. But when you give a feast, invite the poor, the maimed, the lame, the blind. And you will be blessed, because they cannot repay you; for you shall be repaid at the resurrection of the just" (Luke 14:12-14).

At the threshold of the glorious Feast of the Nativity, we need to recall these words and to act according to them. When Christ affirms the necessity of inviting every sort of poor person, He means to tell us that if we want to invite Him to join us in the feast, then we must invite all the poor to the feast and in this way we will have sent Him a special invitation and their presence at the feast will be His own personal presence.

Two weeks before Christmas, we read in the Church the Parable of the Banquet (Luke 14:15-24), which comes directly after the passage taken from the Gospel of Luke above, so as to place even more importance on the centrality to obtaining salvation of love for the poor. Or, as Saint Cyril of Alexandria said, "Because they were hard-hearted, Christ gave them a parable in which He explains to them the nature of the time that He establishes for them." As for the parable itself, it talks about a man who throws a lavish banquet and invites many people to it. None of those invited accept his invitation, making various excuses. He then sends His servant into the town squares and streets in order to invite "the poor, the crippled, the blind and the lame," who immediately accept his invitation. At the end of the parable, the one making the invitation says, "none of those who were invited [and refused the invitation] will taste my banquet."

The one making the invitation in the parable symbolizes God. As Cyril of Alexandria says, "The comparison here represents the truth and is not itself the truth." Cyril then wonders who the servant represents in the parable. He answers, "Who is the one sent? He is a servant. Perhaps he is Christ. Although God the Word is God by nature and the Son of God who proclaimed Him to us, He emptied Himself and took the form of a servant."

The tradition of the Church has realized that in this parable, Christ identifies with the poor of every kind-- that is, with those invited. At the same time, He identifies with the servant who was sent to invite them. Christ is the one inviting and the invited at the very same time! We said that He is the inviter and the invited because the one making the invitation is identical to his servant because his servant is of no less dignity than he is.

At Christmas, we are called to imitate Christ, Whose feast it is, so we invite Him to the dinner by inviting His loved ones among the poor. In this way, we resemble Christ twice over: by playing the role of the one making the invitation and by caring for the poor who are invited just as we care for Christ Himself. Here we are met with Christ's words to His disciples shortly before He was arrested: "The poor you have with you always, but Me you do not have always" (John 12:8). Yes, the poor we have with us always and in them we have Christ with us always.