Source: The Express Tribune

Hebron, Palestinian Territories, January 17, 2016

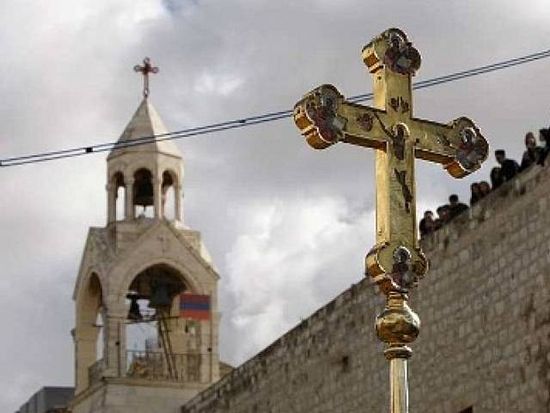

A crucifix is held up in front of the Church of the Nativity during the Orthodox Christmas procession in the West Bank town of Bethlehem January 6, 2011. PHOTO: REUTERS

A crucifix is held up in front of the Church of the Nativity during the Orthodox Christmas procession in the West Bank town of Bethlehem January 6, 2011. PHOTO: REUTERS

Father Eliseev enters the cavernous church, room enough for 200 people, on a Sunday morning. But he won’t be giving a sermon today, nor any week in the foreseeable future.

Eliseev is head of the only church in a city where there are almost no Christians.

His Russian Orthodox Oak of Mamre Church is in Hebron in the Palestinian West Bank, a city holy to both Muslims and Jews, but which holds less significance for Christians.

Hebron has also been among the areas hardest hit by a wave of deadly violence that began in October, putting the church even further out of consideration for pilgrims who might otherwise be enticed to see the site where tradition says Abraham met three angels.

But Eliseev, 46 with a round face and beard, argues the lack of Christian interest in the city is mistaken, pointing out that the church’s gardens contain the Oak of Mamre, where Abraham’s mystical meeting is believed to have occurred.

“This is a very sacred place to me,” he says, wearing a long black robe and traditional black klobuk on his head. “The relationship with this monastery is like a relationship with God.”

Hebron is in particular known for the site Jews refer to as the Cave of the Patriarchs and Muslims as the Ibrahimi Mosque, where the biblical Abraham is believed to be buried.

Around 500 Israeli settlers now live near the site protected by an army buffer zone in the Palestinian city of over 200,000, a constant source of tension and violence.

Both Israel and the Palestinian territories are dotted with Christian communities, small pockets in most cities.

But in Hebron that isn’t the case — Bethlehem, 20 kilometres (12 miles) north, and Jerusalem, a further eight, are Christianity’s holiest sites, but Hebron has far less importance.

Eliseev compared the church’s continued presence to some of Abraham’s visits to the city, including when he overpaid for land where he intended to bury his wife Sarah.

“People said (to Abraham) ‘Are you crazy, where are you going?’”

The church itself is behind a gate on a bustling main road. A guard swings it open and a road winds past the oak to the church — an imposing stone building with two cross-adorned domes.

Its famous oak looks nearly dead — propped up by a metal structure behind a fence.

While outside Hebron bustles, on the grounds there is near silence. It is called a church, but is closer to a monastery.

Neither Eliseev nor the five other Russian priests speak more than a few words of Arabic. They rely on Mohammed, a local Hebron resident who lived in Russia, to translate.

Eliseev, who has been at the site since 2010, admits it can feel like they are forgotten.

“People forget what this place is and why Abraham came here.”

But he will remain there until the church says otherwise. “Maybe I will die here,” he smiles.

Dmitry Dub, a 29-year-old priest, explains they rarely have reason to leave the compound.

“I occasionally walk into town for a shawarma (sandwich) or ride my bike,” he said.

It wasn’t always that way. After the church was bought by the Russian church in 1868, a small number of pilgrims would come — from Russia but also elsewhere.

After the Russian revolution of 1917, religion was suppressed and the church fell into the hands of the Russian Orthodox church overseas.

In the late 1990s, after a decades-long dispute between the two rival Russian Orthodox churches, Palestinian security forcibly evicted the monks and nuns and handed it back to representatives of the Russian Patriarch in Moscow.

On the night of January 6, a Wednesday, Father Eliseev did finally have a rare occasion to lead a communion service as the Russian Orthodox Church celebrated Christmas.

But it came at a fraught time for Hebron. Since October 1, 152 Palestinians and 23 Israelis have been killed in violence across Israel and the Palestinian territories.

Over half the Palestinians killed have been attackers in a spree of lone-wolf assaults, mainly with knives and mostly carried out by frustrated youths.

Around a third of all incidents have occurred in and around Hebron, and the Ibrahimi Mosque/Cave of the Patriarchs site has seen multiple attacks.

In response, Israeli forces have periodically stepped up their restrictions on movement, with night-time raids relatively common.

“We are scared,” said Larisa Loukianova, a Russian Orthodox who married a Palestinian Muslim and moved to Hebron 25 years ago, in front of her family Christmas tree a few minutes from the church.

Unlike other churches in the West Bank, which are mostly attended by Palestinian Christians and have often overtly criticised Israel’s occupation of the territory, Eliseev takes an apolitical line.

Speaking before Christmas, he admitted celebrations would be smaller this year “because of the situation”.

“But should we (abandon) Christmas? That is wrong. But also to celebrate in a big way would be wrong,” he says.

“You need a middle way, like a Christmas in a war.”

They needn’t have worried. On the night of the mass, six priests prepared the church for their guests. Three turned up.