Source: Lessons From a Monastery

February 17, 2016

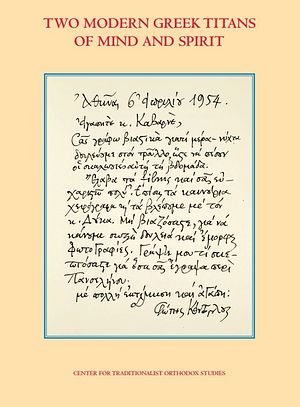

Two Modern Greek Titans of Mind and Spirit: The Private Correspondence of Constantine Cavarnos and Photios Kontoglou. Trans. Archimandite Patapios. (Center for Traditionalist Orthodox Studies: Etna, 2014).

It is truly unfortunate that we in the English-speaking Orthodox world know so little about either Constantine Cavarnos or Photios Kontoglou. Our knowledge of Cavarnos is likely limited to his production of a series of lives of modern Orthodox saints, while our familiarity of Kontoglou is perhaps restricted to his status as the most acclaimed iconographer of recent times. While these contributions alone are undeniably significant, the accomplishments of both men far exceed these limited depictions of them. Two Modern Greek Titans of Mind and Spirit: The Private Correspondence of Constantine Cavarnos and Photios Kontoglou (1952-1965) will provide its reader with ample evidence in support of this claim and quickly bring him to the realization that both are dynamic and important personalities whose contributions to the Orthodox world warrant more serious attention.

Two Modern Greek Titans of Mind and Spirit reproduces in chronological order the 90-letter correspondence between Cavarnos, an academic living in America, and Kontoglou, an iconographer and scholar living in Greece, dating between 1952 and 1965, the time of Kontoglou’s repose. Concerning this collection His Eminence Chrysostomos of Etna rightly observes, “While all the letters in the collection were written by Kontoglou to Cavarnos, in almost every instance they make clear reference to the subjects and topics covered in the exchanges between the two, with frequent direct statements of comments and ideas contained in the latter’s letters” (p.10). Despite this one never feels lost on account of the absence of Cavarnos’ letters, and useful footnotes fill in any small gaps which might cause confusion. Generally, it must be observed that the detailed footnotes are a significant contribution to the volume, providing valuable information concerning persons and situations mentioned in the course of the letters.

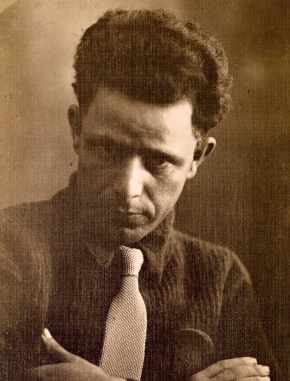

Photios Kontoglou

Photios Kontoglou

The value of the book and its presentation of the correspondence is valuable on many levels. Firstly, it is of historical import, bearing witness to various movements within modern Greek and American culture more broadly, but also specifically within the spiritual life in both places. For example, the letters bear witness to the growth of secularity through the 50’s and 60’s and its impact on the life of the Church; the great problem of spiritual ignorance and its repercussions for the spiritual lives of Orthodox Christians; and – not unconnected with these both – the growth of the Ecumenical Movement in that non-tradition and fearful direction so commonly on display in our own times. We also find much information – perhaps unknown to many – concerning the great effort to resist the aforementioned trends and movements orchestrated by a great many important modern personalities, including the two correspondents. It also documents valuable information concerning the lives and works of many individual figures important in the modern Orthodox world who crossed paths with these two men. For example, the letters record some information concerning the beginnings of the career of Fr John Romanides. Lastly, it preserves important information about the circumstances surrounding the publication of a large number of the two men’s works.

Secondly, the book is significantly valuable as a source of theological material and particularly of the theological thought of Cavarnos and Kontoglou. It must be remembered that both of these figures are significant theologians. Large sections of their correspondence are dedicated to the discussion of the theology of icons and the problematic proliferation of Western paintings enveloping the Orthodox Church at the time – a trend which has happily been reversed in our day. Ecclesiology is also discussed at great length within the context of the development of the Ecumenical Movement and the various un-Orthodox declarations and actions of Athenagoras of Constantinople. Here we find promoted from both sides the proper Orthodox view of Roman Catholicism. Having adopted a long list of heretical believes and practices, it left the Church and thereby forfeited sanctifying grace. Therefore, the discussion of its unity with Orthodoxy centers on its repentance and re-integration into the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church. Also heavily critiqued is any attempt to proceed along the lines of any other ecclesiological model than that articulated in the Church’s tradition.

Dr. Constantine Cavarnos

Dr. Constantine Cavarnos

On the purely physical level, the book is solidly bound, printed on good quality paper, and printed in a large typeset which reads easily. Also helpful in this regard is the fact that the letters have been very well translated, just as we have come to expect from the Center for Traditionalist Orthodox Studies. The style of the letters has been effectively preserved such that what one reads precisely reflects the style of writing described by Metropolitan Chrysostomos in his introduction when reflecting on the way Kontoglou wrote. Several images grace the book’s pages, including photographs of both Cavarnos (both before and after his monastic tonsure) and Kontoglou, and one also finds a two-page reproduction of one of Kontoglou’s handwritten letters which adds something intangible to the work.

With such valuable contributions and an ability to speak to historians, those studying theology, and those interested in the spiritual life, it is impossible not to commend this book and so we conclude with the words of the book’s editors: “We feel it a great privilege to share this legacy, at long last, with those Orthodox Christians and many others who, like ourselves, hold these two great titans of Modern Greek culture, contemporary art and literature, and Orthodox spiritual wisdom in incalculable esteem. May their memory be eternal!” (p.229).