The future Bishop Afanasy (Sergei Gregorievich Sakharov) was born July 2 (old style) 1887, on the feast of the Placing of the Holy Robe of the Most Holy Mother of God in Blachernae. His father, who was from Suzdal, was a farm advisor, and his mother was from a peasant family. Their kindness and piety would be the grace-filled ground upon which their only son’s spiritual gifts would grow. Named after the abbot of the Russian land, St. Sergei of Radonezh, the future bishop acquired the profound, selfless love of the Church and fatherland that distinguished St. Sergius.

Sergei Sakharov’s childhood and youth were spent in the ancient, holy city of Vladimir-on-the-Kliazma.

Sergei’s hardships and trials began in his early childhood, and became the life circumstances that caused him to mature spiritually. The boy lost his father at an early age, but found in his mother everything he needed to worthily enter adult life. She always wished to see him as a monk, and Sergei would be grateful to her all his life for this. Sergei eagerly attended the parish church and never tired during the long services. Church services as the highest prayer was the future bishop’s main love. As a child he felt he would become a servant of the Church, and even boldly told his playmates that he would be a bishop.

The pious youth easily learned handiwork, and could even sew and embroider church vestments. This came in very handy to him later, during exile and the camps, when he sewed vestments and icon coverings. Once Vladyka even made a special portable antimension,1 on which he liturgicized for camp prisoners.

At first, learning did not come easy for the young Sergei, but he did not slacken his efforts, and the Lord generously blessed His future servant and confessor. Unexpectedly to everyone, he graduated from the Vladimir Theological Seminary and then the Moscow Theological Academy with great success. Meanwhile, he never lost his modest and humble relationship to others.

The future bishop especially delved into the subjects of Liturgics and hagiography. In church services he found a distinct theology, as he was very attentive to the texts of the services books. In the margins of his personal service books Vladyka made many notes, clarifications and explanations of particularly difficult words.

While still in the Shuya church school Sergei Sakharov would write his first liturgical hymn—a troparion to the venerated Shuya-Smolensk icon of the Mother of God. His academic work, “The disposition of the faithful soul according to the Lenten Triodion,” was an early testimony to the author’s great familiarity with the subjects of ecclesiastical hymnography, which would remain one of his main interests throughout his life.

Sergei’s first teacher and spiritual instructor was Archbishop Nicholai (Nalimov) of Vladimir, of reverent memory. His next teacher was the famous theologian and strict ascetic, the rector of the Moscow Theological Academy Bishop Theodore (Pozdneyevsky), who also tonsured him in the Protection Church of the Academy with the name Afanasy, in honor of Patriarch Athanasius of Constantinople. From Bishop Theodore’s hands Afanasy would also receive ordination into the deaconate, and then the priesthood. But Vladyka Afanasy would always cherish his monastic tonsure above all.

Bishop Afanasy began his Church obedience at the Poltava Theological Seminary, where he was immediately noted as a talented educator. But the full force of his scholarly theological talent would be cultivated in his native Vladimir Seminary, where he showed himself to be a convinced and inspired preacher of God’s word. He was included in the diocesan council, and invested with responsibility for the quality of preaching in the diocese’s parishes. He would lead discussion and readings at the Dormition Cathedral, shedding light on many burning issues of the time.

Hieromonk Afanasy was thirty years old when the revolution happened in Russia. During that period, the so-called “diocesan conferences” began meeting frequently, and at these conferences people would rise up against the age-old Orthodox foundations of Russian life. All of this demanded a strict ecclesiastical evaluation and an appropriate response.

In the St. Sergius Lavra in 1917, representatives from all the men’s monasteries of Russia gathered for a conference. At this conference Hieromonk Afanasy was chosen as a member of the historical Local Council of the Russian Church of 1917-18, where he would work in the section for theological questions.

At that same time, he began his work on the famous service to All the Saints Who Shown Forth in the Russian Land, which would become a remarkable liturgical monument to his love for his holy Church. To Hieromonk Afanasy belonged the idea of choosing for the stichera on “Lord I have cried” one stichera each from the General Menaion to each rank of saints, and in the canon to organize the saints according to geographical area. Each ode of the canon ended, also at his idea, with a troparion to the icon of the Mother of God most venerated in that area. Synod member Metropolitan Sergius (Starogorodsy) contributed the troparion he wrote beginning with, “As beautiful fruit…” Patriarch Tikhon then reviewed the first draft of the composed service.

The revolution ripped across Russia like a tornado, and a sea of Christian blood was spilled. The new regime began its crude desecration of the relics of holy God-pleasers, the annihilation of the clergy, and the destruction of Orthodox churches. The faithful people saw in these unrelenting catastrophes and persecution against Christ’s Church the fulfillment of the threatening prophecies concerning the fall of Russian Tsardom, its transformation into a “pack of heathen, lusting to destroy each other” (St. John of Kronstadt, homily from May 14, 1907).

In 1919 during an antireligious campaign the bolsheviks began their desecration of something especially dear to the Orthodox—the incorrupt remains of the holy God-pleasers. In Vladimir, as in other Russian cities, a propaganda demonstration of opening the relics to the people was carried out—the relics were displayed uncovered for everyone to see. In order to put a stop to the mockery, the Vladimir clergy led by Hieromonk Afanasy, a member of the diocesan council, placed a guard in the Dormition Cathedral. There were pillars in the church at which the holy relics lay. The first guard—Hieromonk Afanasy and chanter Alexander Potapov—awaited the people crowding at the doors of the church. When the doors opened, Hieromonk Afanasy proclaimed, “Blessed is our God…”The reply was made of “Amen”—and a moleben began to the Vladimir saints. The people entering reverently crossed themselves, made prostrations, and placed candles at the saints’ relics. Thus did the proposed desecration of relics turn into their triumphant glorification.

Soon the Church hierarchs would place the zealous pastor in a responsible position: Now an archimandrite, Fr. Afanasy was appointed vicar of two ancient monasteries in the diocese—Bogoliubov and the Nativity of the Mother of God.

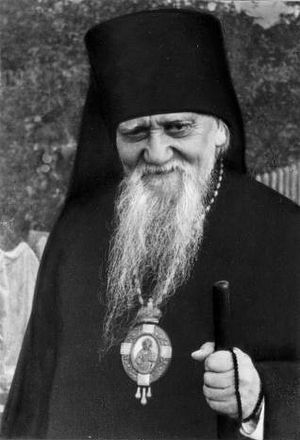

An extremely important and breaking event in the life of Vladyka Afanasy was his elevation from archimandrite to bishop of Kovrov, a vicarate of the Vladimir diocese. This took place in Nizhny Novgorod on the commemoration day of St. Sampson the Hospitable, July 10, 1921. Metropolitan Sergius (Starogorodsky) of Vladimir, the future Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia, presided at the consecration.

The main concern and pain of Vladyka Afanasy’s hierarchical labor was not the opposition of the authorities, nor even the destruction and closure of churches and monasteries, but the formation within the Church of a new schism, known under the name of “renovationism”.

The seeds of renovationism as a schismatic movement, which called for reform in the Russian Orthodox Church, had been sown long before the October revolution. Before the revolution pseudo-Orthodox innovations had penetrated the walls of theological schools and religious-philosophical societies, and were the refuge of a certain faction of the intellectual clergy. The revolutionary authorities used these reformationist ideas to divide the Church; only they relied not upon the intellectual minority, but on the substantial mass of conformists and skeptics within the Church’s fold, who had learned in former times to bow down before any power of Caesar—both the autocratic and the Bolshevist.

St. Afanasy’s opposition to the renovationist schism was not so much a war with heretical convictions as it was a rebuke against the sin of Judas—apostasy from Christ’s Church, the betrayal of its hierarchs, pastors, and laity who were in the hands of the executioners.

St. Afanasy explained to his flock that the schismatics, who were revolting against the canonical hierarchy headed by Patriarch Tikhon, have no right to serve the Sacraments, and therefore the churches where they serve are without grace. He re-consecrated churches desecrated by the schismatics, instructed the apostates to repent together with their parishes, and rebuked those who would not repent. He forbade people to associate with the renovationists in order to shame them; however, he asked not to have any rancor against them for their seizure of Orthodox shrines because the saints, as he said, are in spirit always only with the Orthodox.

The holy hierarch’s first arrest took place on March 30, 1922. This was the beginning of many years of prison trials for Vladyka Afanasy. However, as strange as it may seem, the imprisoned bishop counted his own situation as easier than the lot of those who, remaining in freedom, had to endure enormous pressure from the renovationists. He even called prison an “isolation from the renovationist epidemic.” Vladyka’s path from prison to prison and exile was endless and excruciating. Of the prisons, there were: Vladimir, Taganka in Moscow, Zyryansk, and Turukhansk. Of the camps, there were: Solovki, Belomor-Baltisk, Onega, Marii in Kemerovo province, Temnikov in Mordovia…

On November 9, 1951 the sixty-year-old bishop’s final term of prison camp ended. However, even after this he was kept in total uncertainty of his future, and then settled involuntarily in an institution for invalids at Potma station in Mordovia, where the regime differed little from a prison camp.

The archpastor could be arrested right on the road, as once happened to him while travelling around the Yuriev-Polsky region. From 1937-38 he was arrested a number of times, and prepared for immediate execution.

At the beginning of World War II, Vladyka was sent by prisoner convoy to Onega prison camp in Archangelsk province on foot, and the prisoners had to carry their belongings. As a result of the strenuous travel and hunger, Vladyka became so weak that he was seriously preparing for death…

The Onega camps were exchanged for indefinite exile in Omsk province. In one of the state farms near the city of Golyshmanovo, Vladyka worked as a night guard of the vegetable gardens. Then he was transferred to the city of Ishim, where he lived on the aid sent to him by his friends and spiritual children.

In winter 1942, Bishop Afanasy was unexpectedly sent by convoy to Moscow. The investigations went on for a long time. He was interrogated around thirty different times, usually at night. The interrogations would last four hours, but one time they lasted a whole nine hours. Sometimes it would take four hours to write only one page of protocol, and sometimes, more than ten pages… Not once did Vladyka betray anyone under interrogation, nor did he incriminate himself.

The sentence was pronounced: eight years imprisonment in the Marii camp, Kemerovo province, notorious for its cruelty. The “ideological enemies of the soviet government” were given the heaviest and dirtiest jobs.

In summer of 1946, Vladyka was again sent by convoy to Moscow for new investigations after a false denunciation. But soon the denouncer renounced his own statements, and His Eminence was sent to the Temnikov camps in Mordovia to finish his sentence. He was physically weak and could only weave bast shoes. Two years later he was sent to Dubrov camp (also in Mordovia), where due to his age and physical condition he no longer worked.

Throughout all this, Vladyka never lost his faith in God and feelings of great gratitude to Him. Barely alive after the tortures, holding back his moans, the saint often said to his close ones: “Let’s pray, let’s praise God!” And he would be the first to sing, “Praise the name of the Lord…” This singing would revive him. He would encourage returning prisoners, “Don’t lose spirit. The Lord has vouchsafed you, in His great mercy, to suffer a little for Him. Thank God for this!”

Work in the camps was always grueling, and often dangerous. Once Vladyka Afanasy was appointed money collector, which was burdensome to him. Soon he was robbed of one thousand rubles, and had to report it to the authorities as his own shortfall. Without investigating the matter, the authorities immediately imposed serious penalties on the prisoner.

In Solovki, Vladyka Afanasy contracted typhus. He was threatened with death, but the Lord clearly preserved His sufferer, and Vladyka survived literally by a miracle.

But in this constant distress Vladyka discerned spiritual benefit—the possibility to show the power of his faith. He unwaveringly held to the rule of the Holy Church, never interrupted his prayer rule, praying not only in solitude but also in the company of his prison inmates. Even in the camps he strictly kept the fasts, finding opportunities to prepare fasting food.

He was simple and open with those around him, and found ways to spiritually comfort those who turned to him “with their pain” for support. He was never seen idle—he would work on liturgical notes, or decorate paper icons with beads, or take care of the sick…

On March 7, 1955 Bishop Afanasy was freed from the Potmo invalid institution, which by its prison camp regime finally wrecked his health. At first Vladyka settled in the town of Tutayev (Romanov-Borisoglebsk) in Yaroslavl province, but then chose the village of Petushki as his place of residence.

Although from that time on Vladyka was formally free, the authorities continually hindered his movement. In Petushki, for example, he was permitted to celebrate the services only behind the closed doors of the church, and without hierarchical regalia.

In 1957, the prosecutor of Vladimir province again reviewed the case of 1936, according to which Vladyka Afanasy had been prosecuted. Vladyka was interrogated at home, and the arguments he made in own defense were not admitted. No rehabilitation took place…

Vladyka’s consolation was services in the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra—after all, he remembered his monastic tonsure within its walls, and always considered himself one of its brethren. Several times Vladyka concelebrated with Patriarch Alexy (Simansky), and on March 12, 1959 he participated in the consecration of Archimandrite Nikon (Lysenko) as Bishop of Ufa.

At one of Vladyka Afanasy’s services, the congregation noticed that during the Eucharistic canon he walked above the floor of the church; it was as if he were gently carried out of the altar on a sort of wave…

Vladyka Afanasy had a very hard time with the new stage of liberal persecutions against the Church during the “thaw” period,2 and increased his prayers to Russian saints and the Mother of God—the Protectress of Rus’. He even began to view his retirement as a withdrawal from the struggle with the coming evil and wanted to request an appointment as a vicar bishop, but his ruined health would not allow him to continue this service to society. No matter how hard Bishop Afanasy’s life was he never desponded. To the contrary, in the prisons, camps, and exile he was always brimming with an amazing energy, finding soul-saving work to occupy himself. It was precisely there, within prison walls, that the service so remarkable in the liturgical sense to all the Russian saints was completed. It was finalized after discussions with the hierarchs who had been imprisoned together with Vladyka Afanasy.

One of these hierarchs was Archbishop Thaddeus of Tver, glorified by the Church as a new martyr. Thus, on November 10, 1922, in cell 172 of the Vladimir prison, the first service to All the Saints of Russia was held, using the corrected text.

When his mother died, Bishop Afanasy was not only aroused to fervent filial prayer for her, but also to write his fundamental work, “On the commemoration of the reposed according to the canons of the Orthodox Church,” which was highly appraised by Metropolitan Kirill (Smirnov).

In August 1941, His Eminence Afanasy composed the “Moleben hymns for the fatherland,” filled with profound repentance and extraordinary prayerful power, embracing all sides of Russia’s life. During his period of imprisonment, Vladyka composed hymns “For those in sorrows and various circumstances,” “For enemies, those who hate and harm us,” “For those in prisons and captivity,” “Thanksgiving for receiving alms,” and “For the cessation of wars and for the peace of the whole world”…

St. Afanasy truly sang to God “as long as he had his being” (cf. Ps. 45:1). He sang even at the gates of death, and the Lord preserved His servant for his beloved Church and fatherland.

The years of confessing the Christian faith in camps and prison, as onerous and horrible as they were, became for Bishop Afanasy not loss but gain. They acquired for his humble soul that grace-filled light of the spirit that the world so lacks. People were drawn from all around to that light, each with his own pressing life questions. And these people met a person with a pure soul, filled with ceaseless prayer.

No one ever heard from him a word of murmuring about his prison past. He met everyone who came to him with gentleness, kindness, sympathy, and love. He shared his rich life experience with each, revealed the meaning of the Gospels and the lives of the saints, and helped pastors lead their flocks to true repentance.

The saint loved everything beautiful, seeing there a reflection of eternity, and had the ability to find this beauty everywhere. While living in Petushki, Vladyka received 800 letters per year, and he carried on correspondence with many former prisoners, whose sorrows he felt as if they were his own. At Christmas and Pascha he would send thirty or forty packages to those in need of help and consolation.

Bishop Afanasy’s spiritual children recall how he was simple and attentive with people, and how he appreciated even the tiniest service to him, for which he always tried to show his gratitude.

Living modestly himself, he almost never paid any attention to people’s external appearance. He did not like human glory and honor, and taught others to do good only to the glory of God, so that they would not be deprived of future reward. He instructed that talents are God’s gifts, and one must never be prideful about them.

Once at the question, “How must I be saved?” he answered, “The most important thing is faith. Without faith, not even the best deeds are saving, because faith is the foundation of everything. And second is repentance. The third is prayer, and the fourth is good deeds. And worse than any sin is despair.” Vladyka instructed people to have recourse to confession as often as possible; just as soon as a sin is recognized, one should cleanse it away with tears of repentance.

Prayer filled the saint’s whole life, and was so alive and strong that those who prayed with him would leave everything earthly behind. And many received speedy help through his prayers. Vladyka often said that in difficult times of life we should prayerfully run to the saint whose name we bear. Prayerful recourse to our intercessors—the saints of the Orthodox Church—had particular significance for him. Vladyka hid his clairvoyance, revealing it only in very special cases and only for the sake of his neighbor, to whose needs he never remained indifferent and whose infirmities he so patiently bore.

In August 1962, Bishop Afanasy would begin to say that it was time for him to die. When he was once answered that his close spiritual children would not be able to bear their separation from him, he sternly noted, “Should one really become so attached to a person? By this we violate our love of the Lord. After all, they will not be alone, but remain with the Lord.”

Several days before Bishop Afanasy’s blessed repose, the father superior of the Holy Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra, Archimandrite Pimen, the dean, Archimandrite Feodorit, and monastery confessor Igumen Kirill came and greatly consoled His Eminence. This was the eve of the fifty-year anniversary of his monastic tonsure. On the anniversary day, a Thursday, Vladyka was especially happy, blessing everyone present.

But death was now approaching. Vladyka could no longer speak, and was immersed in prayer. Nevertheless, on Friday evening he quietly said for the last time, “Prayer will save you all!” Then he wrote with his hand on the blanket, “May the Lord save you!”

On Sunday, October 28, 1962, on the day of St. John of Suzdal, the holy hierarch quietly committed his spirit to God. He had foretold this day and hour earlier…

Life taken from: The Life of Holy Hierarch Afanasy, Bishop of Kovrov, Confessor and Hymnographer (Moscow: Otchy dom, 2000) 3-21.